The Scrappy Independents of Mumblegore

By Brian Eggert | October 20, 2024

When I started writing film criticism in the mid-2000s, the horror genre was at a creative low point—what I consider the worst era for horror of my lifetime. The 1990s slasher resurgence spearheaded by Kevin Williamson and Dimension Films had petered out with Scream 3 in 2000, and Hollywood had started to explore cynical new trends to reflect the world after 9/11, the US invasion of Iraq, and Abu Ghraib. Caught in a cycle of torture porn, bleak found footage, and often soulless remakes, the genre saw few titles escape this pattern of angry and mean-spirited pictures, which often left everyone onscreen dead. Many boasted awful characters I couldn’t wait to see die, and when they did, I felt empty for having endured the experience. It reached the point where I began to dread new entries in the genre. And admittedly, I often undervalued exceptions to this strain of mainstream horror dominating theaters. Mumblegore movies were among those I overlooked or missed altogether; though, in the 20 years since the sub-subgenre first arrived, I’ve come to cherish its scrappy minimalism.

To situate mumblegore within the realm of early 2000s horror and understand why such titles were overshadowed by the decade’s onslaught of brutal horror, some context of the genre at the time is necessary. For instance, consider what was popular: 2004’s low-budget Saw launched a franchise that delighted itself by ripping victims to shreds in creative ways, and its sequels returned every year for the remainder of the decade. Hostel and Wolf Creek joined in 2005, riding the wave of hopeless, torture-laden nightmares. At the same time, Michael Bay’s company Platinum Dunes set about remaking classic slasher movies with particularly nasty new interpretations of Freddy Krueger, Jason Vorhees, and Leatherface. Elsewhere, Dark Castle Entertainment remade B-movie classics with impressive production values and cynical storylines, while other studios produced English-language remakes of J-Horror hits. After experiencing so much cruelty and anger, not to mention blatant commercialism at the multiplex, it’s no wonder I had become disenchanted with the genre as a whole.

As ever, there were exceptions to my general anathema. For instance, many of the great horror films from the 2000s come from new international movements, such as the Korean New Wave, New French Extremity, and J-Horror. Mexican auteur Guillermo del Toro earned a name for himself with The Devil’s Backbone (2003), Spain’s J.A. Bayona bowed The Orphanage (2007), and Sweden’s Tomas Alfredson impressed with Let the Right One In (2008). The era would also bring about a rebirth of the zombie. Danny Boyle resurrected the genre with fast-moving “rage-infected” zombies in 28 Days Later (2002), and Edgar Wright and Zack Snyder followed, while George A. Romero also returned to the zombie subgenre he started.

But these titles represent the relative mainstream horror in the 2000s; which is to say, they were released in multiplexes. By contrast, mumblegore movies—most released between 2006 and 2017—often coasted on the festival circuit before locating a small audience, usually at home. They spread by word of mouth and almost never received wide theatrical distribution, if they appeared at the multiplexes at all. Many of them debuted on VOD, then a new method of distribution for independent cinema; though, it would be a mistake to lump them in the same quality category as ‘90s direct-to-video fare.

But these titles represent the relative mainstream horror in the 2000s; which is to say, they were released in multiplexes. By contrast, mumblegore movies—most released between 2006 and 2017—often coasted on the festival circuit before locating a small audience, usually at home. They spread by word of mouth and almost never received wide theatrical distribution, if they appeared at the multiplexes at all. Many of them debuted on VOD, then a new method of distribution for independent cinema; though, it would be a mistake to lump them in the same quality category as ‘90s direct-to-video fare.

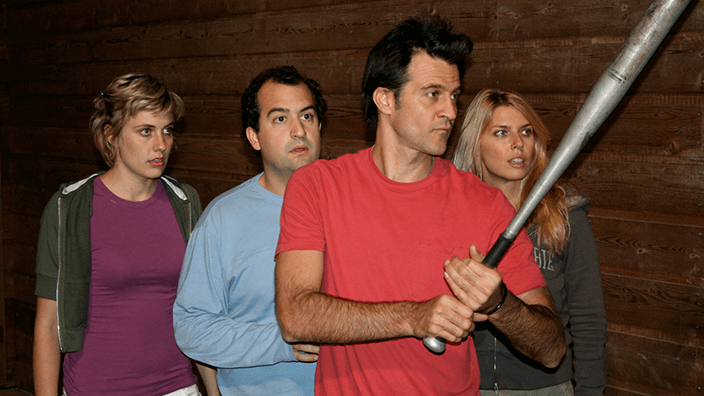

Mumblegore’s origins stem from the independent subgenre known as mumblecore, spearheaded by Andrew Bujalski (Funny Ha Ha, 2002), Lynn Shelton (Humpday, 2009), the Duplass brothers (The Puffy Chair, 2005), Joe Swanberg (Hannah Takes the Stairs, 2007), and Lena Dunham (Tiny Furniture, 2010). Notable for their naturalistic, sometimes improvised performances, talky scripts, aimless plotting, and low-budget production values, mumblecore films usually centered on the relationships of twenty- and thirty-somethings.

While mumblecore is a relationship-focused subgenre of finding-yourself dramedies that arrived in the early 2000s, mumblegore applied scares and minimalist aesthetics to that formula for a more marketable film. After all, low-budget horror has always made a profit, ranging from the cheap but atmospheric programmers produced by Val Lewton at RKO in the 1940s (Cat People, 1942) to shoestring horror mogul Larry Fessenden’s work in the 1990s (Habit, 1995).

The horror offshoot of mumblecore became a reality when a few of its filmmakers, along with many contemporary underground filmmakers interested in horror, realized that a similar independent spirit could be achieved in the commercially viable horror genre. Often shot on the cheap end of low budgets, with money borrowed from family members and independent investors, these genre-savvy productions could easily draw an inbuilt audience of horror fans, turn a profit, and make a name for their intrepid young directors. But mostly, the filmmakers were just having fun playing in a sandbox they loved—similar to how Sam Raimi (The Evil Dead, 1981) and Peter Jackson (Bad Taste, 1987) began their careers with gloopy splatterfests before eventually going Hollywood.

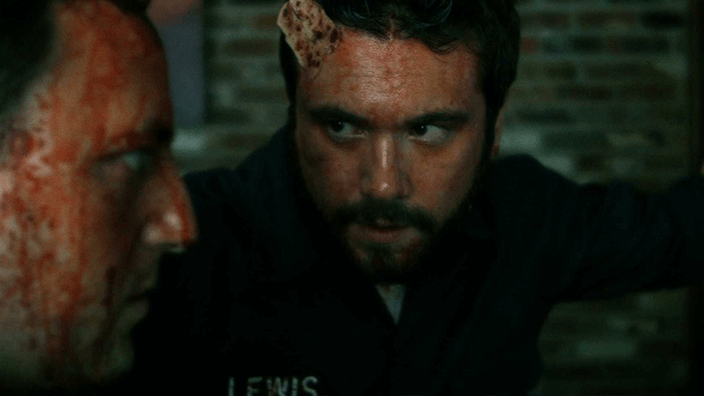

Often made using new, inexpensive digital camera technologies or 16mm film stock, many of these low-fi productions featured the same actors from mumblecore: Swanberg, Amy Seimetz, Mark Duplass, and Greta Gerwig all crossed over into the scary subgenre. Since they didn’t have the budgetary dollars for monsters and special effects, the films found terror in prolonged dread, clever jump-scares, and stylized camerawork. But that didn’t stop directors like Ti West from using killer bats and zombies in his debut feature, The Roost (2005), produced by Fessenden’s independent Glass Eye Pix. However, more often than not, mumblegore explores everyday evils, such as people who kill for greed, or even worse, those who kill for no reason at all.

Often made using new, inexpensive digital camera technologies or 16mm film stock, many of these low-fi productions featured the same actors from mumblecore: Swanberg, Amy Seimetz, Mark Duplass, and Greta Gerwig all crossed over into the scary subgenre. Since they didn’t have the budgetary dollars for monsters and special effects, the films found terror in prolonged dread, clever jump-scares, and stylized camerawork. But that didn’t stop directors like Ti West from using killer bats and zombies in his debut feature, The Roost (2005), produced by Fessenden’s independent Glass Eye Pix. However, more often than not, mumblegore explores everyday evils, such as people who kill for greed, or even worse, those who kill for no reason at all.

It took time for mumblegore to pop, if it ever did. After releasing several small features at minor festivals, a group of friends and filmmakers collaborated on an anthology project called The Signal, co-directed by Dan Bush, David Bruckner, and Jacob Gentry. The movie depicts a brain-scrambling broadcast on television, radio, and cell phone signals that drives its victims to violence. The filmmakers cast their friends, such as AJ Bowen, Anessa Ramsey, and Justin Welborn, who have appeared in many more independent horror flicks since. And they got their production to screen at the Sundance Film Festival in 2007.

A year later, when Magnolia Pictures put the film into a limited theatrical release, it earned some disturbing buzz when a story broke about a man who entered a California theater and stabbed two moviegoers in a grisly scene straight out of the movie. Horror fans ate up the similarities, and though the box-office take amounted to a mere $400,000, the film’s budget was one-eighth of that. I remember seeing The Signal in the theater two days after the stabbing had been reported. It was opening night at Marcus Cinema in Oakdale, Minnesota, and the theater was sparsely attended. A handful of horror fans had gathered to see what the buzz was about. Every once in a while, you couldn’t help but look behind you, just in case someone was back there with a knife.

After The Signal, several mumblegore filmmakers collaborated on V/H/S, launching a successful anthology movie series in 2012 that continues today with five increasingly polished sequels and two spinoffs. What started as a mumblegore project has since become too popular to still earn that label. Elsewhere, the Duplass brothers deconstructed the cabin-in-the-woods slasher with their hilarious and creepy Baghead (2008). Ti West earned accolades for The House of the Devil (2009) and The Innkeepers (2011). E.L. Katz explored economic desperation with Cheap Thrills (2013). And Adam Wingard developed two cult classics with his wry home invasion thriller You’re Next (2013), followed by his tense, genre-defying action-slasher The Guest (2014)—but given their budgets, they test the categorization in mumblegore. Few of these films broke out of their isolated niche, however.

Writing in LA Weekly, Amy Nicholson observed that mumblegore was at “an unsustainable sweet spot between invisibility and expectations. The only way its auteurs can keep making what they want is if they accept a micro-budget ceiling.” Indeed, most of the filmmakers associated with mumblegore have since branched out to do larger projects for Hollywood studios. Wingard went from A Horrible Way to Die (2010), a grainy production shot on a digital camera, to overseeing a $200 million budget on Godzilla vs. Kong (2021). Bruckner went from The Signal to making a reboot of a famous horror franchise with 2022’s Hellraiser. West broke through with X and Pearl for A24 in 2022—with price tags of $15 million and $10 million, respectively—which he rounded out into a trilogy.

In the years since mumblegore movies first appeared, much has changed. Digital cameras have gotten better and become the standard, eliminating the look of those handheld experiments from the 2000s. Independent horror has also become more popular and even flourished thanks to targeted production companies willing to invest in new projects, such as Blumhouse, A24, Neon, and RJLE, along with horror-centric streaming services such as Shudder and ScreamBox. There’s a mini-major infrastructure behind independent horror now. But in the early 2000s, the filmmakers behind mumblegore were collaborators who were experimenting with a few thousand dollars and using their friends in front of and behind the camera.

In the years since mumblegore movies first appeared, much has changed. Digital cameras have gotten better and become the standard, eliminating the look of those handheld experiments from the 2000s. Independent horror has also become more popular and even flourished thanks to targeted production companies willing to invest in new projects, such as Blumhouse, A24, Neon, and RJLE, along with horror-centric streaming services such as Shudder and ScreamBox. There’s a mini-major infrastructure behind independent horror now. But in the early 2000s, the filmmakers behind mumblegore were collaborators who were experimenting with a few thousand dollars and using their friends in front of and behind the camera.

So a major factor in how one can define this obscure group of mumblegore films goes beyond what we see onscreen—the modest aesthetics, amateur performances, chatty characters, and uncomplicated narratives. Much of it also has to do with the production forces under which the film was made. Today there are films such as Offseason (2021), directed by Mickey Keating and starring two mumblegore regulars, Swanberg and Jocelin Donahue. At first glance, it might seem like a mumblegore movie. But Offseason was financed by RLJE, part of the small industry built around independent horror films today. While similar examples often attempt to replicate or pay homage to the unallied—essentially so—mumblegore films of yesteryear, they remain too dependent on market forces to qualify.

Mumblegore remains a brief blip on horror’s timeline, neglected, forgotten, and rarely celebrated outside of a few online circles. In preparing to write about these films, I found no in-depth scholarly analyses and only a few amateur appreciations. Even a Google search of “mumblegore” delivers results for “mumblecore” first, with the search engine struggling to find much discussion of mumblecore’s horror sibling.

Still, looking back at these films, they reveal the first steps of several filmmakers into something bigger, but not always better. Ingenuity and imagination drive these films more than many of the filmmakers’ subsequent, occasionally mainstream projects. Whether it’s a matter of necessity breeding invention or simply young filmmakers experimenting with their craft and not following Hollywood formulas, there’s something inspiring about these micro-budget productions. They do a lot with very little, and in today’s cinema of commercial excess, less is more.

Click the title to read the review:

- The Signal (2008)

- Baghead (2008)

- The House of the Devil (2009)

- A Horrible Way to Die (2010)

- The Innkeepers (2011)

- You’re Next (2013)

- Creep (2014)

- The Guest (2014)

- The Sacrament (2014)

- Creep 2 (2017)

(Note: This article was originally posted to Patreon on October 2, 2023.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review