Reader's Choice

The House of the Devil

By Brian Eggert |

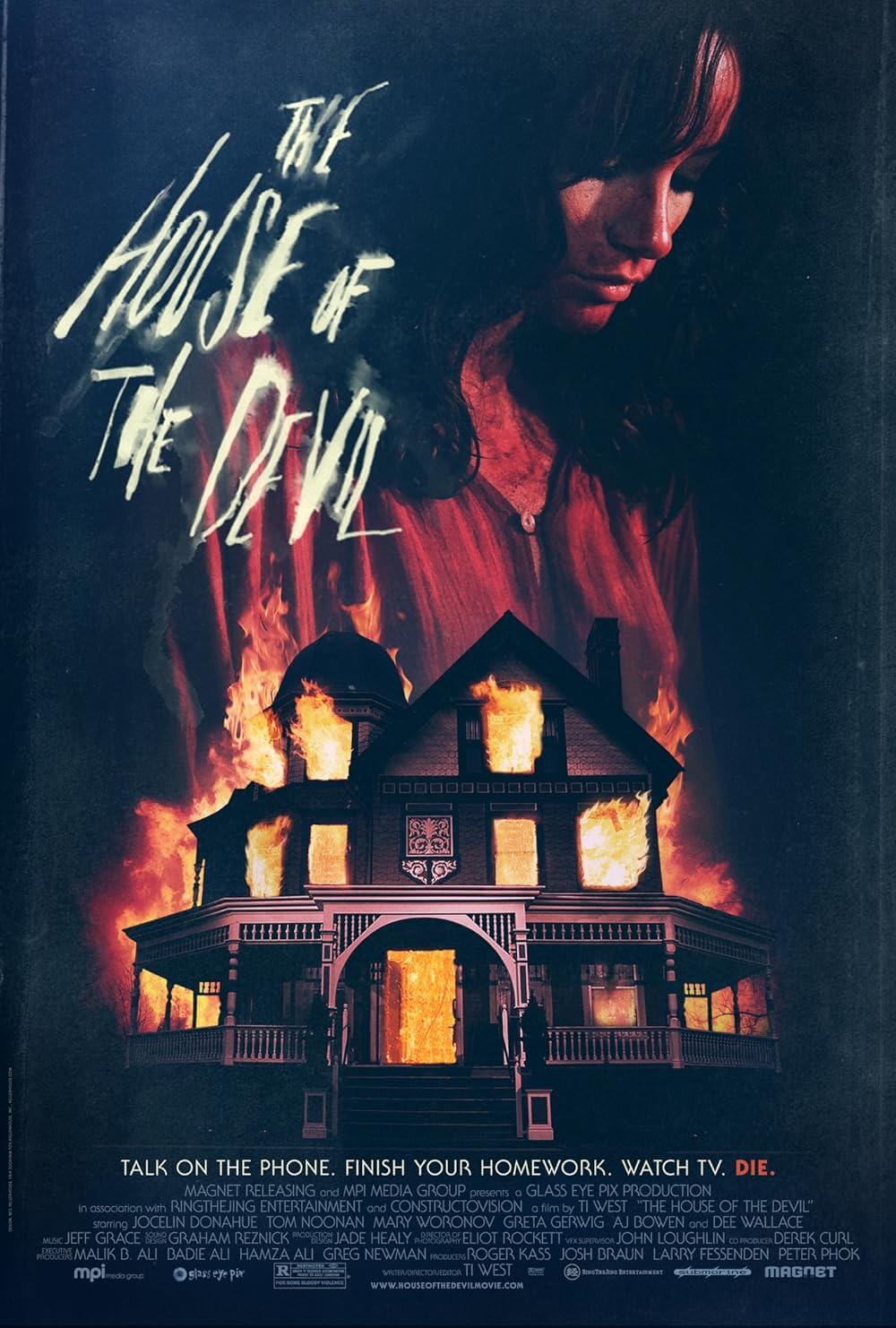

The House of the Devil is a nerve-shattering chiller and a committed exercise in pastiche, rigidly adhering to the low-budget horror aesthetics of yesteryear. From the intentional grain that appears onscreen to the simplistic babysitter-terrorized-by-cultists plot to the dated décor, soundtrack, and poster design, everything about it feels like a throwback to the horror movie renaissance of the 1970s and 1980s. If someone told you this was a long-lost flick from forty-some years ago that was only recently discovered, you’d have no choice but to believe them, since the filmmakers went to great extremes to devise and shoot a movie whose mise-en-scène draws from its period of choice. Released in 2009, the film marked a critical breakthrough for writer-director-editor Ti West, whose capacity for slow-burning suspense and formal imitation caught the attention of festival-goers and cult audiences with this throwback hit. Fortunately, West’s approach is less about nostalgia and reference points than an homage to an era, and he replicates that effect with convincing formal techniques and narrative minimalism.

Similar to his second feature, Trigger Man (2007), West shows his aptitude and patience for constructing long sequences focused on mundane action, which slowly builds dread until the screen bursts with energy. His tantric approach in The House of the Devil comes accented with the atmosphere of yesterday’s horror, in that he has enough control over the cinematic apparatus to flawlessly replicate and employ B-movie tropes. Although he had shot Trigger Man on digital, West and cinematographer Eliot Rockett used 16mm film stock on The House of the Devil to get the look of a grainy microbudget production, deploying telephoto zooms, an earthy color palette, and immersive master shots for a ‘70s feel. The whole production is almost worthy of inclusion in the Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez project Grindhouse (2007), capturing the flavor of an era without stealing from specific films. So while the film may conjure thoughts of John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978) and Stuart Rosenberg’s The Amityville Horror (1979) in the genre-savvy viewer, West hasn’t made a mere reference machine.

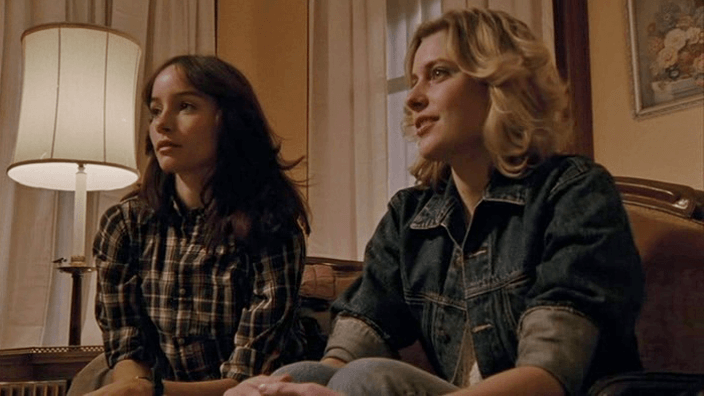

The film opens with a familiar conceit, claiming to be based on “true unexplained events” during the Satanic Panic—an era when the culture couldn’t believe that the average person might be evil, and so the Religious Right spread fear by making unfounded claims that every kidnapping, murder, or sex crime had a Satanic component. And why wasn’t the government doing anything about it? It’s a cover-up, of course. But the film also plays on the fear that babysitters make easy targets, setting up the story in Halloween mode. West’s answer to Laurie Strode is the quiet college student Samantha (Jocelin Donahue), who hopes to get away from her flaky roommate by moving into a house for rent. But she’s struggling with money. A “Babysitter Needed” flier posted on the campus job board provides an answer to her problems. The job pays $100 for four hours of work. Her chatty friend Megan (Greta Gerwig), West’s answer to P. J. Soles and Nancy Loomis, warns that taking the job is insane. And even while Samantha acknowledges the gig is too good to be true, she proceeds anyway. There wouldn’t be a movie if she didn’t.

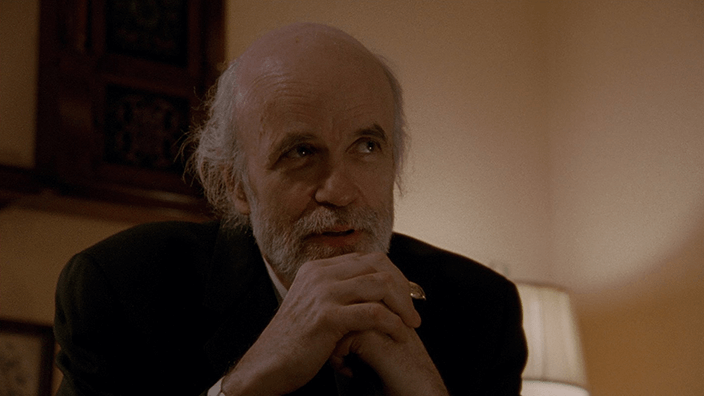

Megan drives Samantha to the job, and on the way to the creepy old country house in the middle of nowhere, they pass by a cemetery. Here’s a film that still finds the cemetery a spooky place, and the brooding shot of gravestones at night gives the viewer goosebumps. But not more than Mr. Ulman (Tom Noonan), the towering figure who hired Samantha, and his equally unnerving wife (Mary Woronov). Soon enough, he confesses: Samantha won’t actually be babysitting; rather, she’ll be watching over his elderly, senile mother-in-law while he and his wife go out to see the lunar eclipse. When Samantha says she’s not interested now, he quadruples her money and promises to make it as “painless as possible.” Samantha doesn’t flinch at the remark, but we do. Questions ensue: “Are you a teacher?” Samantha asks. “No… Not exactly,” Mr. Ulman replies with a faint smile. “Are you an astronomer?” “No… Not exactly.” The only thing Mr. Ulman knows is that “There’s a number for pizza on the refrigerator.” He mentions it three times. “I know how you college kids like pizza.” But ordering pizza is the last thing Samantha should do.

Megan drives Samantha to the job, and on the way to the creepy old country house in the middle of nowhere, they pass by a cemetery. Here’s a film that still finds the cemetery a spooky place, and the brooding shot of gravestones at night gives the viewer goosebumps. But not more than Mr. Ulman (Tom Noonan), the towering figure who hired Samantha, and his equally unnerving wife (Mary Woronov). Soon enough, he confesses: Samantha won’t actually be babysitting; rather, she’ll be watching over his elderly, senile mother-in-law while he and his wife go out to see the lunar eclipse. When Samantha says she’s not interested now, he quadruples her money and promises to make it as “painless as possible.” Samantha doesn’t flinch at the remark, but we do. Questions ensue: “Are you a teacher?” Samantha asks. “No… Not exactly,” Mr. Ulman replies with a faint smile. “Are you an astronomer?” “No… Not exactly.” The only thing Mr. Ulman knows is that “There’s a number for pizza on the refrigerator.” He mentions it three times. “I know how you college kids like pizza.” But ordering pizza is the last thing Samantha should do.

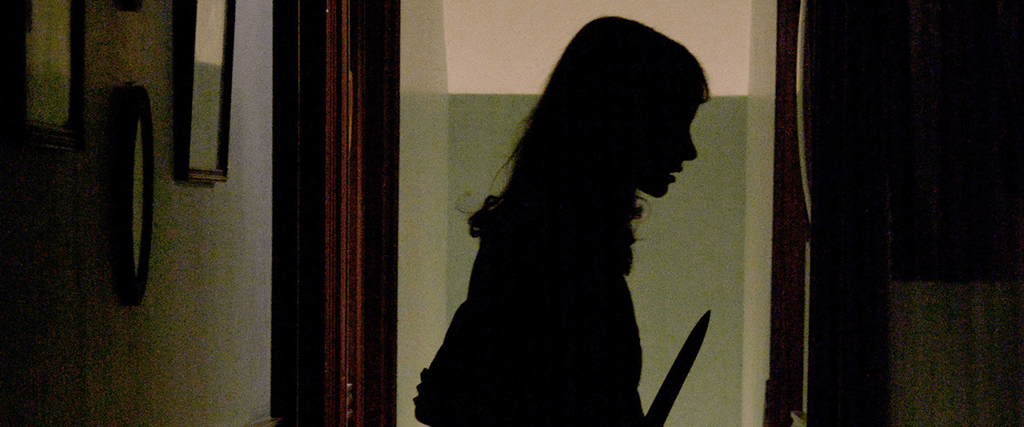

Wandering the big dark house alone at night, with only Night of the Living Dead (1968) on TV, Samantha becomes unsettled. The senile mother-in-law keeps to herself, but the wood floor creaks upstairs; Samantha can hear the old woman moving in the house. Samantha tells herself “everything’s fine” and to “get a grip” when she’s scared. She orders that pizza, and it tastes funny. But West has already established in an earlier scene with Megan that the greasy pepperoni pizza in this movie tastes funny, so perhaps it’s not concerning. And for a while, we think it might just all be in Samantha’s head—until we see the shocking fate of Megan after she drops Samantha off; until Samantha becomes drowsy after the pizza; until the camera takes us behind a locked door, panning over the leftovers of a bloody ritual. But West doesn’t saturate his picture in bloodshed. He holds off until the last fifteen minutes before things go south, and when they go, it’s a disturbing and refreshingly exposition-free downward spiral into robed cultists, a deformed witch, and demonic pregnancy.

At the time, West was one of what critic Amy Nicholson called the “young misfits who are revolutionizing indie horror movies.” With his contemporaries, such as Adam Wingard, David Bruckner, Glenn McQuaid, Joe Swanberg, and Radio Silence—who would collaborate on 2012’s V/H/S anthology—West helped bring new life to the late-2000s, early-2010s horror scene with entries in the mumblegore sub-subgenre. Together, his collaborators supplied an alternative to the omnipresence of Hollywood fare—the Platinum Dunes remakes of slasher classics, endless Saw and Paranormal Activity sequels, and torture porn that dominated the era. Although some of his mumblegore contemporaries would go on to work in Hollywood franchiseland, West remains defiantly independent as of this writing. However, his name has never been more popular with the advent of his X trilogy produced by A24. But in 2009, West was still working with budgets well under $1 million and had the freedom to control his small production shooting in Connecticut.

Indeed, the film’s $900,000 price tag was a step up from West’s previous two shoestring budgets, evidenced by the cast of familiar faces: From the independent film scene, Gerwig plays a small but memorable role, and like her appearance in Baghead (2008), carries over from mumblecore to mumblegore. But most notably, Noonan (The Monster Squad, 1987), Mary Woronov (Night of the Comet, 1984), and Dee Wallace (Critters, 1986) as the landlady, all of whom have starred in their fair share of schlock, lend their genre cred. West had already worked with Noonan on his debut feature, 2005’s little-seen The Roost, which also co-starred and was produced by independent horror icon Larry Fessenden’s production company, Glass Eye Pix. Fessenden had roles in The Roost and Trigger Man, but he remained behind the camera as producer on The House of the Devil.

Indeed, the film’s $900,000 price tag was a step up from West’s previous two shoestring budgets, evidenced by the cast of familiar faces: From the independent film scene, Gerwig plays a small but memorable role, and like her appearance in Baghead (2008), carries over from mumblecore to mumblegore. But most notably, Noonan (The Monster Squad, 1987), Mary Woronov (Night of the Comet, 1984), and Dee Wallace (Critters, 1986) as the landlady, all of whom have starred in their fair share of schlock, lend their genre cred. West had already worked with Noonan on his debut feature, 2005’s little-seen The Roost, which also co-starred and was produced by independent horror icon Larry Fessenden’s production company, Glass Eye Pix. Fessenden had roles in The Roost and Trigger Man, but he remained behind the camera as producer on The House of the Devil.

West’s direction is expertly crafted here, representing a vast leap in his control over tone and style compared to his earlier two features. From the yellow opening titles to the narrative simplicity, The House of the Devil is a chameleon that replicates the look and feel of its antecedents. The film unfolds at a measured pace, allowing us to share in Samantha’s many silences and exploration of the Ulman house. Though the screenplay doesn’t offer many gradations to Samantha as a character, Donahue’s presence, feathery hair, and dance montage to The Fixx’s “One Thing Leads to Another” make her a familiar brand of vulnerable young woman. Similarly, West doesn’t spend much time exploring the Ulmans’ motivations, though it’s enough to know the lunar eclipse supplies them with a chance to impregnate Samantha with what we can only assume is the antichrist—complete with hints of Satanist conspirators in Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Omen (1976).

Best of all, the viewer doesn’t spend The House of the Devil’s 95-minute runtime thinking about where West draws inspiration from, either in aesthetic or thematic terms. Instead, we remain engrossed in the accumulation of disturbing details and how they will play out, even as the stylistic exercise remains at the forefront. West knows how to build tension by holding a shot longer than another filmmaker might, how to ratchet suspense with slow zoom, and how to let actors such as Noonan and Woronov do their thing. But he also knows how to introduce humor with charismatic performances—especially Gerwig’s blithe presence, cut brutally short—and how to disquiet us with the likes of mumblegore regular AJ Bowen as a bearded, shifty-eyed killer. If the stylistic conceit keeps the viewer at a slight remove, it’s a pleasure to watch West and his cast play in established genre territory so well.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on November 9, 2023.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review