Reader's Choice

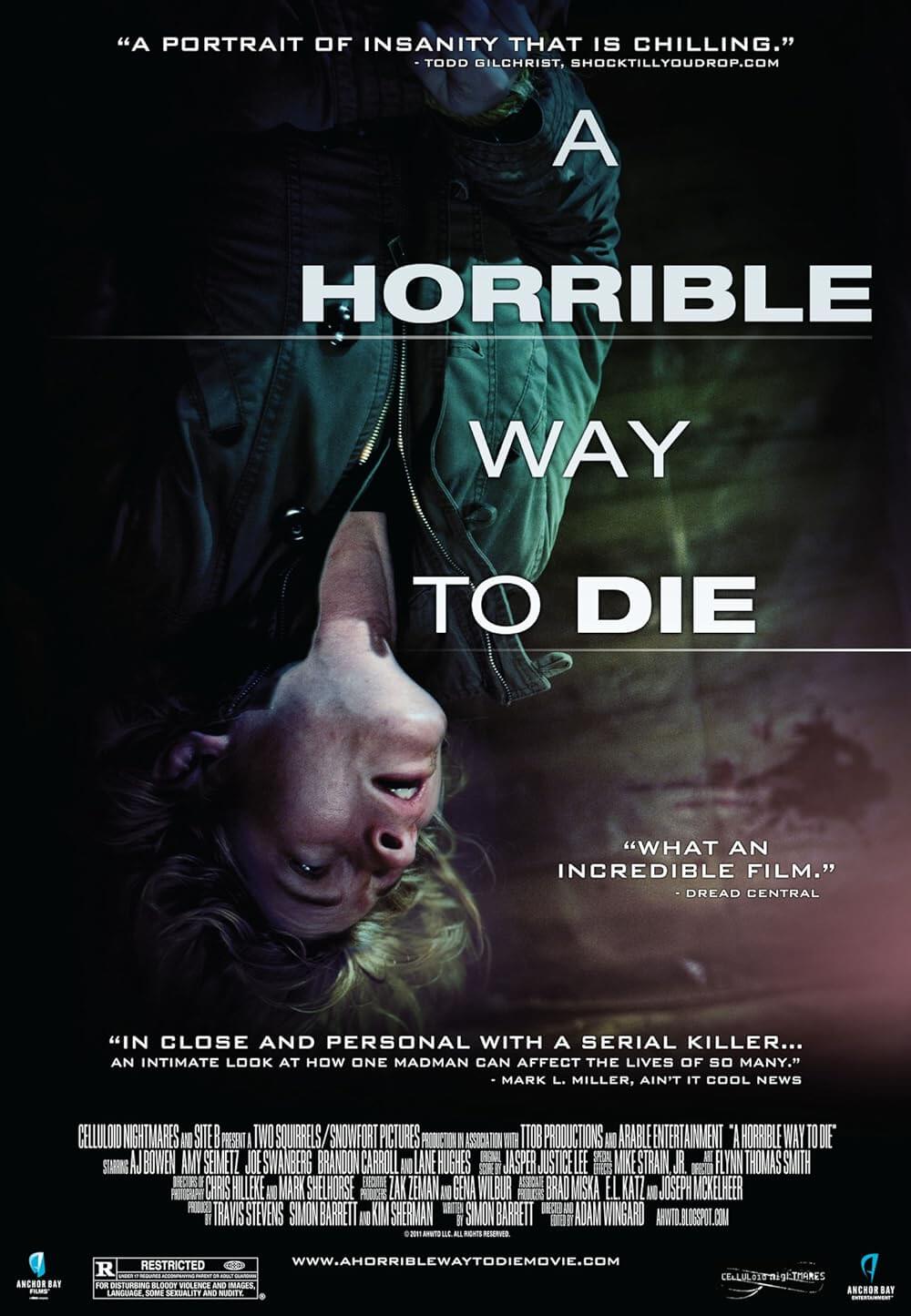

A Horrible Way to Die

By Brian Eggert |

A bleak, unforgiving look at a serial killer and those left in his wake, A Horrible Way to Die adopts the perspective of Sarah, played by Amy Seimetz. She’s a three-months-sober alcoholic who works at an orthodontist’s office, and something awful happened in her past. It’s the reason she decided to stop drinking and attend regular Alcoholics Anonymous meetings; the reason she’s hesitant to start dating again; and the reason the story unfolds in a fractured, nonlinear structure, fading in and out of scenes from her numbed, fuzzy, and traumatized point of view. Although the film has earned comparisons to Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) for its willingness to engage the mind of its central murderer—Garrick Turrell, played by A. J. Bowen, who gives his character chilling humanity beneath his depraved impulses—the film is more affecting as a portrait of how far people will go to rationalize and maintain normalcy. Written by Simon Barrett and directed by Adam Wingard, the team behind You’re Next (2013) and The Guest (2014), it features a cast of mumblegore regulars in a film that’s slow-burning, unnerving, and among their best work together.

A Horrible Way to Die is also an efficient, layered example of how independent horror can flourish, despite having few resources. Using tone, minimalist digital photography, and a small cast, the microbudget production creates unbearable tension for a fraction of the cost of a Hollywood thriller. Completed for a reported $75,000, the film thrives because its talented cast, sharp writing, and skilled director have no other choice—they must make it work. They have a few modest locations, captured in Missouri. But they’re not throwing together random scenes captured on the fly. There’s a cohesive formal agenda on display, with Wingard editing the roving cinematography by Chris Hilleke and Mark Shelhorse down to a precise, considered, and symbolic aesthetic. Watching the film can be unsettling and disorienting, not only for the substance of the narrative but for the visual agenda, which tackles its subject with wobbly, searching movements that often blur, going out of focus from one nonlinear scene to the next, as though the whole film is remembered in the aftermath of a deeply troubling experience.

Bowen receives top billing as Garrett, who we first see in a parked car, looking particularly stressed and sleazy with a mustache and thick sideburns. When he opens his trunk and helps the woman inside to her feet, he seems almost considerate. “You’re gonna be fine,” he tells her. “Just relax.” It almost sounds true. But then he strangles her. Garrett has escaped prison during a transfer and is on the loose. Shown out of sequence in an impressionistic structure, scenes depicting Garrett’s escape include him using a loose screw to take out several prison guards, securing a vehicle, and slaughtering at least two young women on his journey. Wingard cross-cuts between Garrett’s progress and Sarah’s story, with the two inevitably colliding near the finale. In the meantime, Sarah attends an AA meeting and hesitates before agreeing to a date with Kevin (Joe Swanberg), a fellow recovering alcoholic who seems nice enough. But something’s off about him. His words of encouragement about her three-month milestone feel forced, and so do his compliments about her purple sweater pairing well with her hair.

Bowen receives top billing as Garrett, who we first see in a parked car, looking particularly stressed and sleazy with a mustache and thick sideburns. When he opens his trunk and helps the woman inside to her feet, he seems almost considerate. “You’re gonna be fine,” he tells her. “Just relax.” It almost sounds true. But then he strangles her. Garrett has escaped prison during a transfer and is on the loose. Shown out of sequence in an impressionistic structure, scenes depicting Garrett’s escape include him using a loose screw to take out several prison guards, securing a vehicle, and slaughtering at least two young women on his journey. Wingard cross-cuts between Garrett’s progress and Sarah’s story, with the two inevitably colliding near the finale. In the meantime, Sarah attends an AA meeting and hesitates before agreeing to a date with Kevin (Joe Swanberg), a fellow recovering alcoholic who seems nice enough. But something’s off about him. His words of encouragement about her three-month milestone feel forced, and so do his compliments about her purple sweater pairing well with her hair.

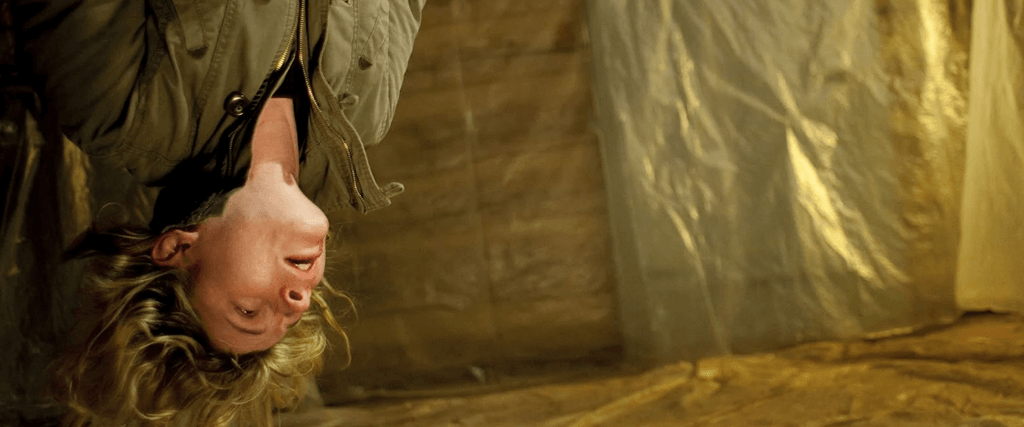

Wingard builds tension with his structure, with early glimpses of devastating moments that will be revealed in full later. He shows Sarah entering a room, pushing aside sheets of plastic with a horrified look on her face. He shows staccato flashes of the carnage that Garrett left behind. But he also builds on the relationship between Garrett and Sarah with flashbacks to before the killer’s arrest. These scenes reveal how Garrett maintained a kind, affable dynamic with Sarah, who was often too drunk to question why he was going out for mid-night strolls or coming home so late from work. Maybe she always knew something was off, and alcohol fuelled her denial and self-medicated her into numb complacency. Or maybe her alcoholism shielded her from any suspicion of Garrett, prompting her subsequent shock at the discovery, along with a sense of guilt that she should have known all along but didn’t because she consumed so much alcohol. Either way, she feels responsible, and it leads her down the road of recovery in the aftermath.

Seimetz gives a fully embodied performance in A Horrible Way to Die, her nose always stuffy and pink, her appearance somewhat shabby and thrown together. She looks like someone recovering in more ways than one. Wingard sets the film from her viewpoint, his shaky, handheld camera too close to the image and often swaying in and out of focus making it difficult to to see the full picture—an apt visual metaphor for Sarah’s denial or inability to learn about Garrett earlier, and also her alcoholism. Having appeared together in a dozen features, Seimetz and Swanberg play characters in a shaky, desperate relationship. Sarah is eager to move on with her life, yet Kevin is so clearly off and holding back, evidenced by his false grin and seemingly innocent mistakes. When Kevin invites her to an Italian restaurant he likes, Sarah finds herself surrounded by walls covered in wine. Given his presence in Sarah’s AA group, it might be an error. Or maybe not. Maybe Kevin has found a subtle way to torture his date? And to what end? Swanberg’s shitty, rather creepy “oopsie” smile over the gaffe is enough to give you chills.

By comparison, Bowen’s killer proves more inherently violent but somehow less dangerous than Garrett’s followers. He seems almost reasonable and rational next to, say, the crackpot played by cartoonist Frank Stack whom he meets at a gas station, spouting off about transponders in the power lines. Moreover, references throughout the film to Garrett’s online fanbase implant the notion of a veritable incel group who worships him and plans to follow in his footsteps—though, they misjudged their idol. By the climactic scenes that reveal Kevin and his so-called coworkers prompted Garrett to escape and save Sarah from their plans, A Horrible Way to Die takes a disturbing detour, revealing the central killer as a victim not only of his uncontrollable impulses but of his demented, intentional, and downright evil followers. Wingard and Barrett subvert the serial killer in wholly unexpected ways by the final moments, leaving the viewer shaken and unsure where to place our sympathies.

By comparison, Bowen’s killer proves more inherently violent but somehow less dangerous than Garrett’s followers. He seems almost reasonable and rational next to, say, the crackpot played by cartoonist Frank Stack whom he meets at a gas station, spouting off about transponders in the power lines. Moreover, references throughout the film to Garrett’s online fanbase implant the notion of a veritable incel group who worships him and plans to follow in his footsteps—though, they misjudged their idol. By the climactic scenes that reveal Kevin and his so-called coworkers prompted Garrett to escape and save Sarah from their plans, A Horrible Way to Die takes a disturbing detour, revealing the central killer as a victim not only of his uncontrollable impulses but of his demented, intentional, and downright evil followers. Wingard and Barrett subvert the serial killer in wholly unexpected ways by the final moments, leaving the viewer shaken and unsure where to place our sympathies.

Propelled by Jasper Justice Leigh’s brooding, tonal, and choral score, A Horrible Way to Die is a terrifically acted and thoughtfully conceived film. It’s independent horror at its best, operating at a level that considers its budgetary limitations a challenge to overcome with smart writing and filmmaking. At times, the filmmakers’ simplicity can feel disorienting. Wingard and Barrett fill minutes of screentime with out-of-focus images—such as the foregrounded Christmas lights that adorn Sarah’s apartment appearing as large color blobs onscreen. But this austerity works in harmony with the narrative. So what initially seems cheap and even off-putting becomes a reflection of the characters’ subjectivity and respective tunnel visions, one rooted in violent impulses, the other in blocking out troubling realities. Whereas most mumblegore titles traffic in pastiche or playful genre exercises, A Horrible Way to Die remains one of the few examples that eviscerates with its desperate situations and broken characters.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on October 18, 2023.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review