Top 10 Films with Ambiguous Endings

By Brian Eggert | May 5, 2023

By design, ambiguous endings have a way of hanging around in the mind

For me, an ambiguous ending is different from the sort of unresolved conflict in David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007), where investigators never catch or clearly identify the killer. I would also disqualify the open-endedness found in The Graduate (1968), where the runaway couple’s future and happiness remain in doubt. It’s also not the kind of conclusion found in Do the Right Thing (1989), where the lingering moral uncertainty serves as a social prompt to the audience.

Rather, my way of identifying an ambiguous film ending centers on cryptic conclusions that challenge the viewer to understand what happened in the narrative, often leaving the explanation up to individual interpretation.

There are a few similar lists online, and I looked at then for inspiration. Some of what I found gave me ideas. Many of them showed me what not to do. Most of the lists I came across featured titles like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or Blade Runner (1982), two films with equivocal endings, to be sure, but they do not resist clear interpretation. When I watch those titles, I am so convinced of what happens because they’re so decipherable based on evidence in the film that they no longer seem ambiguous. Their endings require reading, of course, but I do not feel they were conceived to leave the viewer unable to settle on an analysis or explanation. In fact, in these two examples, the filmmakers have made clear statements about what they intended their ending to mean.

When I set out to make my list, I sought to include films that leave me genuinely unable to decide what happens in the end. These titles resist closed-book interpretation and float in the mind like an unanswerable question. Even though I have watched the films on this list many, many times, I still haven’t decided how they end. The filmmakers have left the choice up to me, but each of the films resists a confident interpretation, even while inviting me back to experience them again.

Given the nature of the topic, I will be discussing the films’ endings in detail. If you wish to remain unspoiled, skip the paragraphs related to the films you haven’t seen.

10. Blow-Up (1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni’s Palme d’Or-winning mystery was a sensation upon its release in the mid-1960s, as intellectuals and college campuses debated the meaning of the film’s conclusion. David Hemmings plays a brash photographer in Swinging London who snaps a photo of what he suspects is a murder victim. The closer he looks by blowing up the image, the less he sees. Antonioni’s film would go on to inspire two other, similar films with The Conversation (1974) and Blow Out (1981). Though, those productions feel like closed cases compared to Antonioni’s conclusion. After Hemmings’ character discovers the supposed murder victim’s body has been moved, he comes across a couple of mimes playing invisible tennis and helps out. It forces him, and the audience, to wonder: Was it all an elaborate cover-up? Or has he just been chasing nothing and investigating a murder when none has been committed? This landmark film inspired a generation of young filmmakers to embrace equivocation.

9. eXistenZ (1999)

While everyone in the world was talking about The Matrix in the spring of 1999, I was trying to convince them that David Cronenberg’s mind-bending work of science-fiction, which came out three weeks later and was far more satisfying. Jennifer Jason Leigh is a video game designer whose game console is a living organism that connects to people with an umbilical-like cord that’s inserted into a port in the spine, creating an experience that’s difficult to differentiate from reality. The story follows Leigh’s character, accompanied by a PR novice (Jude Law), on the run from a group of purist fanatics trying to kill her for polluting the concept of reality. The film’s many twists and turns leave the viewer uncertain whether or not the characters are still playing the game, anticipating what would become gamer addiction and the increasingly blurred lines between virtual/digital spaces and reality. In the final moment, one gamer asks, “Tell me the truth, are we still in the game?” Your guess is as good as mine.

8. Inception (2010)

Inception is arguably the most Nolany of all Christopher Nolan films, except perhaps Memento (2000). It blends rousing action scenes, an all-star cast, a high-concept scenario, and a temporally complex structure. Say what you will about Nolan and his emphasis on puzzles over emotion, but he did something rare here: he delivered a crowd-pleasing blockbuster that, despite its open-ended conclusion, somehow satisfied viewers when it robbed them of a clear resolution. When Leonardo DiCaprio’s corporate spy spins his totem, it’s supposed to tell him whether he’s dreaming or has returned to reality. In the final frame, the top keeps spinning. It wobbles a bit, but we never find out whether he returned to his family, or if he remains trapped inside his layers of dreams. It’s an ambiguous conclusion that continues to inspire fanatical theories and analysis, which sometimes shift depending on the viewer’s state of mind—and make revisiting the film quite rewarding.

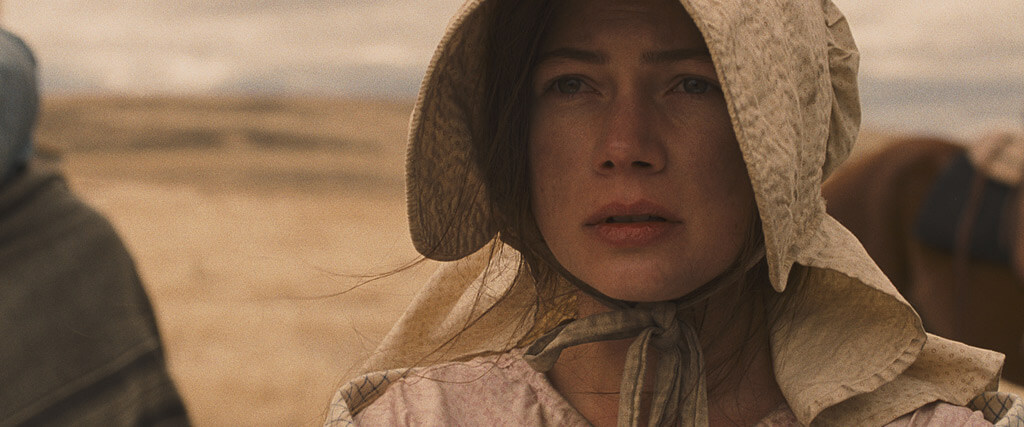

7. Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

Kelly Reichardt’s austere and intentionally-paced Western follows a small group of wagons en route to Oregon in 1845. But rather than follow the Oregon Trail, their guide Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood) leads them into unknown and potentially dangerous territory. Michelle Williams plays a headstrong member of the group who questions their leader, but the others won’t listen to a woman’s logic. The film critiques how easily people will follow a blustering idiot if he’s loud enough, a man, and has a position of authority. When they find a lone native who promises to lead them to water, Meek stokes their fear, believing they’re being led to their deaths. But Williams’ character trusts the native. Reichardt doesn’t confirm if they find water, walk into a trap, or make it to Oregon before fading to the credits. Although history explains what happened to the party, Reichardt leaves it to the viewer and how we judge the situation.

6. Personal Shopper (2016)

Before Olivier Assayas earned the prize for Best Director at Cannes for his work on Personal Shopper, his film earned boos from the festival’s typically vocal audience. They hated the uncertainty of the conclusion, which leaves questions about whether Kristen Stewart’s medium is haunted by the ghost of her twin brother, by another ghost altogether, or has simply projected the film’s strange events herself. What’s more, what do we make of the killer, or the scene that follows nothing at all through a hotel lobby and out an automatic door? That uncertainty is what makes the film so entrancing and rewatchable. Stewart’s character, in arguably the actor’s finest performance, doesn’t quite know what to think. And Assayas shows us plenty we cannot explain. In the final scene, she asks out loud, “Is that you… Or is it just me?” Something answers with a thump, but what is it?

5. Taste of Cherry (1997)

This Iranian film from Abbas Kiarostami is another Palme d’Or winner, and another film whose ending leaves the final choice up to the viewer. But where the titles on this list so far have been mostly genre pictures, Kiarostami’s soul-searching drama settles on an exceedingly human question: whether or not to go on with life. Homayoun Ershadi plays Mr. Badii, a middle-aged man who drives around the outskirts of Tehran, looking for someone to check on him the next morning. He has already dug a grave for himself, and that night, he will either choose to kill himself or choose to live. Of course, he struggles to find someone who will either bury him or drive him home the next morning. But when Mr. Badii lies down in the grave during a thunderstorm, Kiarostami leaves his ultimate choice unknown. Like many of Kiarostami’s films, the narrative invites the viewer to examine their own lives. Does one allow the oppressiveness of the world to get the better of them, or do they learn to live for what beauty they can find in an often depressing world?

4. Caché (2005)

Austrian provocateur Michael Haneke has a career filled with ambiguous endings. None have prompted so much debate as Caché. The title, meaning “hidden,” says it all. When Anne and George (Juliette Binoche, Daniel Auteuil), a yuppie couple in Paris, start to receive videotapes containing footage of their house, it prompts George to uncover long-buried secrets about his family’s mistreatment of an adopted Algerian boy. The narrative gradually digs into France’s past crimes and colonial rule over Algeria, but questions remain about who exactly sent the tapes. Haneke’s long, unmoving shots dwell on a single scene, demanding that we look closer at what’s right before us. The film’s final shot outside of a school hints at a few possible explanations for the keen-eyed viewer, but Haneke doesn’t confirm what the images mean. Rather, his ambiguous ending serves as a reminder that we should all keep looking closer at history to reveal the truth.

3. The Thing (1982)

The final scene of John Carpenter’s bleak masterpiece rests on Kurt Russell and Keith David, who find each other in the Antarctic amid burning rubble. Their entire camp has been overrun by an alien organism that can replicate human beings exactly, and many of their colleagues have turned into horrifying displays of the alien’s imitative powers. Exhausted, both men worry that the alien may be hiding in the other. The story ends in a superbly grim fashion, with the implication that, even if one of them is the alien, they’re too tired to do anything else except sit in the cold and die. And if the alien has imitated one of them, the cold will simply preserve it for the next expedition to come along and thaw it out, allowing it to spread. Viewers have interpreted shadows and minor clues for answers, and annoyingly, Carpenter has since shed light on what he thinks happened. But in the film-text, the ending remains unclarified, leaving viewers either faced with the end of our heroes or the end of civilization as we know it.

2. Rashomon (1950)

A lone woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) and a priest (Minoru Chiaki) escape the rain inside a crumbled temple to go over three conflicting witness accounts of a rape and murder trial. Director Akira Kurosawa’s landmark tale of varying perspectives inspired films like The Usual Suspects (1995) and Ridley Scott’s The Last Duel, but even those examples suggest some manner of absolute truth. Kurosawa acknowledges that truth lies in the eyes of the beholder, and furthermore, people often remember events to serve their own desires. As the adage goes, everyone’s the hero of their own story. When the woodcutter adds what he witnessed to the mix, and it’s different too, Kurosawa leaves us with no certainty about what happened. Moreover, he shakes our sense of truth to the core, forever implanting the notion that subjectivity will shape perception, and thus the nature of truth. The idea proved so impactful that it’s been replicated in countless films and even legal terminology to indicate how eyewitnesses usually prove unreliable due to a myriad of psychological effects.

1. A Serious Man (2009)

A strong case could be made that Rashomon deserves the top spot on this list, given its impact on the ambiguity of storytelling itself. But for me, no film better captures the idea that “we can’t ever really know what’s going on” than Joel and Ethan Coens’ A Serious Man, my personal favorite of their films. Many of the Coens’ films have ambiguous endings. And as I developed this list, I thought about including Raising Arizona (1987), Barton Fink (1991), No Country for Old Men (2007), and Inside Llewyn Davis (2013). However, A Serious Man ingrains their career’s central theme—people desperately searching for order in the universe, only to find that none exists—into a narrative about a professor hoping to understand his own misfortunes.

Michael Stuhlbarg plays Larry Gopnik, who teaches Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle to confused students and suffers like the character from the Book of Job. Larry’s life has come undone—with an impending divorce, tenure application, troublesome brother, delinquent son, and uncertain health—and he hopes to meet with a rabbi for answers. But the film teaches us that there’s no justice in the world, no order, and certainly nothing to suggest that there’s a plan. The Coens imply that the less we search for answers, the better, when the opening titles from Rashi read, “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you.” Yet, Larry is incapable of that. And so, just as Larry’s problems seem to resolve themselves, the final chilling image of a tornado appears. You could say Larry’s last-minute lapse in morality incurred God’s wrath, or you could say the ending underscores the randomness of the universe. Either way, systems of thought like philosophy and religion can’t provide guarantees. It is the perfect ambiguous ending, reminding us all that our ends will be ambiguous.

(Note: This list was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on December 15, 2021. Thanks to Martha for selecting this topic!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review