Sundance Recap and Reviews – Part 1

By Beau Stucki | February 7, 2019

Precariously situated in the icy mountains of northern Utah, the Sundance Film Festival is a haven for movie-lovers bold enough to crowd the small city during the snow-blown winter. The festival was founded by a-lister Robert Redford but prides itself as a champion for diverse independent cinema. The marketing this year was themed around “Risk” and that was reflected in the movie choices – for better and worse.

Over 2,000 feature films and more than 9,000 short films were submitted. Of those, only 112 of the former and 73 of the latter made the cut. Sundance is a competition and distribution festival – so the studio representatives were there, ready to purchase. Netflix, Amazon, A24, HBO, Sony, and others bought up titles you can expect to be hitting the big and small screen throughout the year.

In my first season attending as a member of the press, I was able to see just over 30 titles during the 10-day event.

My reviews will be published in three parts. Check out Part 2 and Part 3.

The Nightingale

The Nightingale

Spotlight

The Nightingale is a story of brutality told with brutality. 1829 was a harsh time in Tasmania. Under British rule both conscripted convicts and the Aboriginal tribes suffered. This movie pulls together women and children, with minority ethnicities like the Irish and Aborigines, to give a 136-minute lesson on victimhood and power politics.

The plot follows relative newcomer Aisling Franciosi in a raw and no doubt taxing performance as Clare—a young Irish convict known for the beauty of her voice and leered at by the soldiers whom she tends to and entertains. One soldier, a psychopathically ambitious officer played by Sam Claflin, finds a particular delight in abusing her, and the horrific lengths he undertakes to sait his lust are the catalyst for the revenge tale that ensues.

Jennifer Kent (The Babadook) seems more skeptical of us as viewers than we are of her as the director of this movie. There is hardly a moment that is not underlined, emphatically stated, and repeated to be sure we did not miss the point. The heartfelt aims and righteous anger of the film are largely drowned out by the movie’s palpable conviction that it is breaking new ground. The movie does have suspense and weighty drama, a talented cast, and rich production design, but its scope is hardly revolutionary. At a certain point, the outright viciousness on display (and its staggering ubiquity) begin to detach us from the story rather than pull us in. Once we are detached, it becomes easier to notice those little problems most every movie has—cracks in the plot, oddities in character choice, exaggeration in the sound design, etc. 2/4 Stars.

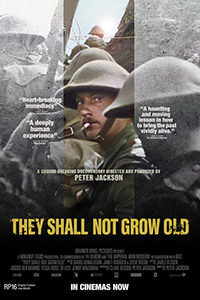

They Shall Not Grow Old

They Shall Not Grow Old

(A special Warner Brothers screening event, not directly associated with Sundance)

The question of whether They Shall Not Grow Old is a good movie is almost of no account. In his debut documentary, Peter Jackson and his team have created something which has never been seen before—presenting neglected historical footage in an entirely new way, with color, sound, and narrative. It ought to be seen if only for its unprecedented immersive power. This is one of those few occasions when it is well worth the extra money to view the film in 3D.

The documentary was officially released last year* to commemorate 100 years since the ending of the First World War, but so far it has only had sporadic releases in America. In a genre that is dominated by gargantuan epics, it is a credit to the film that it carries such impact at a breezy 99 minutes. It will linger long after.

The film is, of course, fiction—in the way that all film is fiction. The stories we are given are filtered through memory, the voices we hear do not belong to the men we see, the sounds of explosions were created by gifted foley artists, the color of each soldier’s eyes or hair is an approximation. We can not truly experience The Great War, nor do we want to, but thanks to this film we have another piece of the puzzle. A vivified bit of history. Roger Ebert once called movies empathy machines. If that’s so then Jackson has greased the cogs and tightened the springs.

*Due to an unfortunate quirk of timing the movie will be ineligible for consideration by the Academy Awards in either 2018 or 2019. Other accolades and word-of-mouth will have to be sufficient to alert people to this limited release. 4/4 Stars.

The Sunlit Night

The Sunlit Night

Premieres

The past couple decades have given rise to a genre of find-yourself indie quirk comedies, and The Sunlit Night fits squarely in this box. We follow struggling young American artist Frances (Jenny Slate) as she flees family drama and a brusk breakup to take a summer internship in Norway where she can paint with abandon, stand in front of sweeping Instagramable vistas, meet a host of eccentric characters, and cavort about in various states of undress.

The beats of the plot and the motivations of the characters are not inherently lamentable, but the film suffers from a lack of authenticity. Some of the characters appear to be doing stand-up bits or overblown caricatures. And the constant oscillation between moments at which we are supposed to laugh and moments at which we are supposed to be moved come off as more cloying than flavorful.

It is ironic that the movie is at least in part about being decisive. “Art is about making decisions,” one character angrily quips, but the movie (and perhaps the book upon which it is based) struggle with that very thing. In fact, the movie is so steeped in stereotypically millennial whimsical-yet-angsty indecision that it treats the act of choice itself as a novelty. While some (millennial or otherwise) may find commiseration in this or that likable moment or quotable line, the sum of these parts has no staying power.

The arresting sublimity of Norway’s bucolic scenery, the milquetoast mug of Zach Galifianakis, and the svelte Slate in a state-of-nature are all picturesquely photographed, but this simply isn’t enough payback for our investment. 1.5/4 Stars.

The Sound of Silence

The Sound of Silence

US Dramatic Competition

There are movies whose premise alone is enough to intrigue even the most jaded of moviegoers. The Sound of Silence is one such. The movie introduces us to a science at once foreign yet strangely familiar in our post-millennial landscape. Peter Sarsgaard plays a house tuner, an investigator of urban noise. In the course of his workday, he visits the homes of various open-minded New Yorkers to assess what noises may be causing undue stress, irritability, or restlessness. He might diagnose the problem as the discordance of the AC unit, or the D flat hum of the refrigerator. In the case of his lonely new client Ellen (Rashida Jones), the toaster may be the problem.

It is easy to see why Sarsgaard was attracted to the role. He imbues the eccentric scientist with a sober fastidiousness that brooks no nonsense and sees not even the slightest hint of silliness in his profession. His scholarly poise invites confidence. In his mental arena, he is adroitly sensitive and keenly perceptive; in other facets of life he is oblivious.

Jones is seasoned for her approachable role and she provides a more self-aware foil to our hero. There is a sly nod to What’s Up, Doc? (1972) in the casting of Austin Pendleton. Unfortunately, he is underused in this movie —as he is in movies in general.

It isn’t exactly a flaw that the movie is able to use the sheer ipseity of its premise to cover up a story that is a bit by the numbers. The movie smacks of Woody Allen’s output from the 1990s and has sparks of wit and moments of clever satire. If it weren’t for the lack of boldness in the third act it might have made the list of great rom-coms, but even falling short of that mark the movie remains charming and inoffensive. 3/4 Stars.

Velvet Buzzsaw

Velvet Buzzsaw

Premieres

Velvet Buzzsaw is hard to define. One might say it tells a quasi-cautionary tale about art as commodity and pretension as personality. It is a story where characters can say lines like “Before the sublime, the whole body quivers” without cracking a smile—vapid characters who thrive on perception and appearance and take the same care to garnish themselves with intellectual accouterments as they do designer shoes and modish outfits. If these characters strike you as ripe for a satirical skewering, the movie agrees with you, yet never quite seems to get there.

The movie isn’t so much genre-bending as it is genre-convoluting. There is a slow build toward true horror—where characters are punished for their (plentiful) sins, but despite many implications, this isn’t what we get. There is camp and comedy, but these too never really take hold. Before it reaches full steam (think a riff on the Final Destination franchise) it has given us a deluge of characters, rumors, vices, motifs, set-ups, dilemmas, and moments of seemingly great import that never deliver.

This is all the more disappointing because there is a wealth of potential in the premise and cast. The creator Dan Gilroy is capable of exposing the seedier aspects of humanity with style, as we know from his deft handling of Nightcrawler (2014). Infusing his new project with more blatant elements of dark comedy is not on the face of it a bad decision, but the situations aren’t used to full advantage. At one point an art dealer mistakes several sacks of garbage for the next great work of a modern artist—thus the movie commits the double sin of being both heavy-handed and borrowing old jokes.

The movie has already had its day in the sun, with the bizarre mid-festival release date chosen by Netflix. Even with its bevy of talent, I suspect it will not remain in the zeitgeist for long. 2/4 Stars.

Relive

Relive

Premieres

The setup of Relive will be new to you if you haven’t seen its cousin Frequency (2000). In this version, a taciturn cop loses his favorite niece to a violent crime only to discover that by some miracle he is able to communicate with her via phone calls. In these calls, she is not dead but existing happily two weeks before her brutal demise. Attempting to change the course of events is what leads us down the rabbit hole of this serpentine story.

The cop is played by David Oyelowo and the niece by Storm Reid. Both are gifted actors who struggle valiantly against the rising tide of cliche and contrivance, but in the end, the preponderance of absurdity is too great and the movie collapses into silliness. It is rare to find a script that compels each character to explain their motivations so frequently and yet manages to be so very confusing. It is a tremendous credit to the actors that in one particular scene in a dinner they are able to get through the dialogue with straight faces. I can say with sincerity that I am eager to seek out future work by both performers.

Because the last third is so perversely amusing the movie would almost be considered watchable but for the sheer tedium of the first stretch. Its sudden drop from dully predictable to dizzyingly convoluted hits us with such force that we are at least awake for the exasperating finale.

Just who the film is aiming for is another unanswerable question. The movie seems primed for the PG-13 thriller crowd and would hit the target but for one startlingly vicious scene. I won’t be surprised if this is cut before release. 1/4 Stars.

The Mountain

The Mountain

Spotlights

From the first evocative shot, The Mountain defines itself as a picture apart from the narrative bustle of Hollywood. The painterly confidence of the movie’s light and framing establishes a tone that is boldly arthouse, and we are reminded of images created by artists like Edward Hopper or Dan Winters. Coldly voyeuristic, torpid, reminiscent, and melancholy, if not bleak.

The plot as such follows a young man (Tye Sheridan) who exists on the edges, isolated from whatever society he is in. He soon drifts, or is ensnared, into the companionship of a traveling doctor who specializes in the practice of lobotomy—the scrambling of the brain’s prefrontal lobe to produce an almost catatonic state. The doctor is played by Jeff Goldblum who, despite a surprisingly effective performance as an almost ghoulish harbinger of slumbering doom, cannot help being comical on occasion (or we cannot help but see him thus) against the ostensible gravitas of the movie.

“Is it dangerous?” one character asks about the lobotomy procedure, and we are immediately struck by the preposterous futility of the question. Is suicide dangerous? Risking death is dangerous—undergoing it is merely a consequence of the previous action, or inaction. And indeed, in this film the many characters we do see undergo the grim procedure are only accepting a technicality —their listless, laconic frames were lobotomized long ago. In the world of The Mountain, our sympathetic abhorrence of this somnambulistic state is meant to be swallowed up by the relative (and somehow horrific) peace it brings. Giving up, it says, is the one release from the pain of living. The only two truly vivacious characters seem to loathe their own existence and seek detachment through sex or alcohol or both.

We can be sure that director Rick Alverson would reject the idea that the highest calling of the artist is to entertain, but just what he supposes his calling to be is unclear. The film meditates so languidly and at such a length that we must be forgiven for wondering whether or not it is sleeping. Despite what we call singular vision and a photographic prowess, The Mountain is a study in lobotomy in more ways than one. 1.5/4 Stars.

State of the Union

State of the Union

Indie Episodic

State of the Union is told in ten segments, written by Nick Hornby and directed by Stephen Frears. The concept is deliciously simple—a husband and wife (Chris O’Dowd and Rosamund Pike) meet at a pub adjacent to their new marriage counselor for a ten minute tête-à-tête before each session. We eavesdrop on each of these conversations in real time.

The ease of the setup allows Hornby and Frears to focus on dialogue —and what razor focus! The rapid-fire perspicacity is reminiscent of something from Howard Hawks or Preston Sturges (whose name is dropped in one episode). The banter is far too scintillating to be natural, but it is delivered with such sincerity and skill we accept the people on screen as entirely real and root for each in turn as they sound and spar.

That sympathy is a great credit to the series. There is no higher praise than that O’Dowd and Pike are able to dance through these pages of endless dialogue with a finesse that allows us to like them both for and in spite of their humanity—for there is a lot of frankness and flaw.

Frears’ camera is not ostentatious. A table for two isn’t exactly pure cinema, but the stage would not be the ideal format either. We need the intimacy the camera gives us. It is soon apparent that the real marriage reparation is happening here; at the table, him with his beer, her with her wine, each with their list of grievances, fears, memories, and hopes. We don’t want to miss a minute. 4/4 Stars.

Beau Stucki is a traveling writer and entrepreneur. He co-runs the film discussion group This Movie Club.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review