Reader's Choice

Zombi Child

By Brian Eggert |

“Listen, white world, as our dead roar. Listen to my zombie voice honoring our dead.”

– René Depestre’s poem “Cap’tain Zombi”

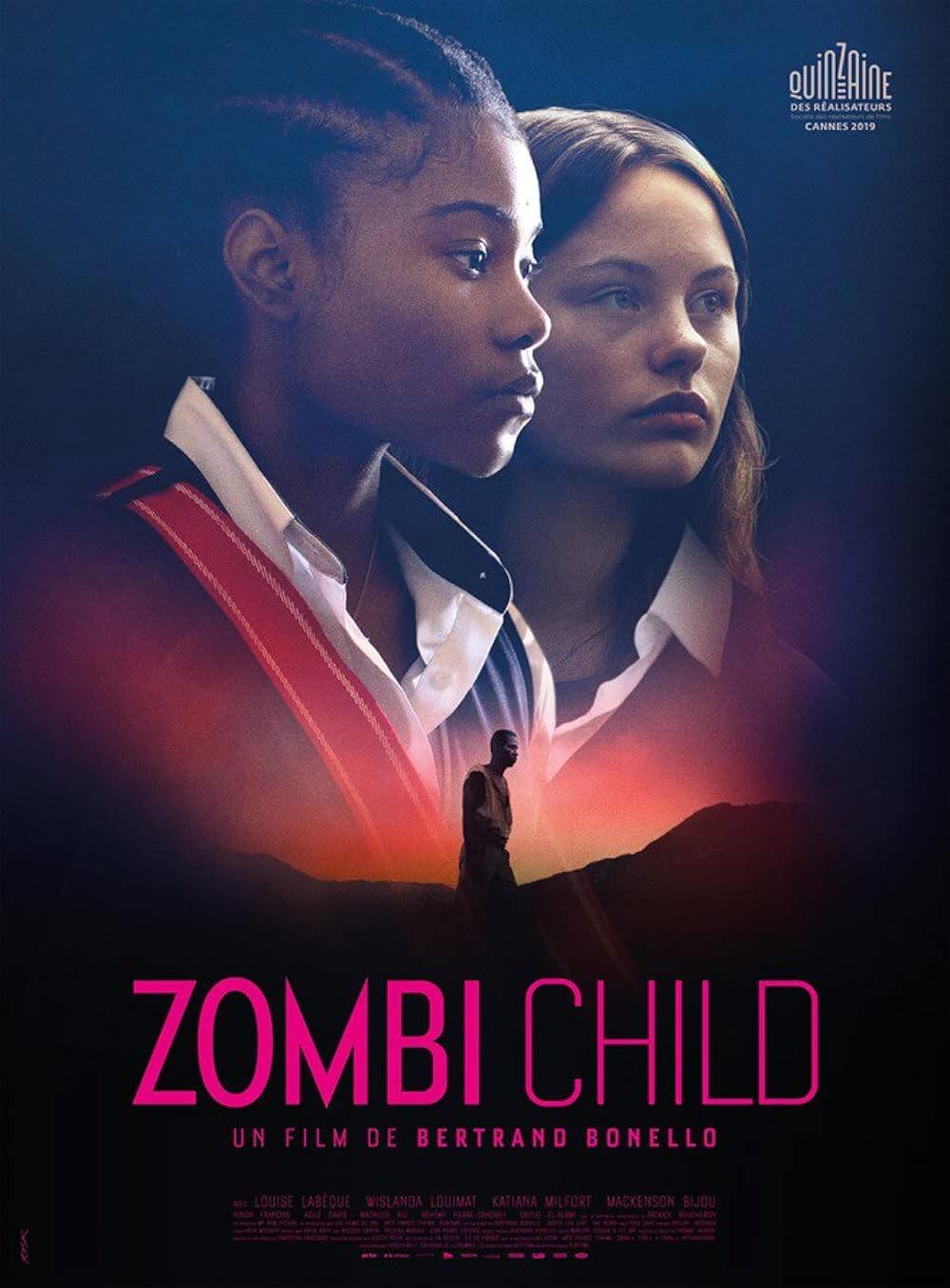

Zombi Child, Bertrand Bonello’s slyly political genre trap, adopts the name and pretense of a horror film to confront matters of French identity, colonialism, and cultural appropriation. Defiantly conceptual, the French filmmaker’s 2019 feature looks at first glance like a coming-of-age drama spiced with a dash of Haitian Vodou magic. But Bonello never does anything in straightforward terms, and Zombi Child is no exception. Blending ethnographic attention to Haitian folk culture with an intellectual underpinning that investigates France’s history, the director’s typically unconventional approach raises questions about what he intends to convey. A reactive might wonder why a white Frenchman is making a film immersed in Haitian Vodou, and whether that constitutes cultural appropriation. Another perspective may view the film as a response to cultural appropriation, portraying the real horror of how the French treat cultures they’ve ruled over with a sense of otherness and mysticism. Zombi Child challenges the colonizer’s view, using the trademarks of a genre picture in service of a pointed critique of France’s mask of liberty as it compares to their historical behavior. Thoughtfully conceived and performed, the film is a mesmerizing experience that approaches Haitian culture with openness and the French treatment thereof with a critique stemming from the country’s colonial history.

Bonello uses the real-life story of Clairvius Narcisse as a springboard for his intricate narrative. The L’Estère-born man claimed that, in 1962, he became ill and collapsed; he was pronounced dead and buried. His wife didn’t see him again until 1980, when he returned home, almost unrecognizable, explaining that he never died. The situation might evoke thoughts of The Return of Martin Guerre (1982), where a soldier returns to his village after the Hundred Years’ War, though no one can be sure it’s really him. But in Haiti, Clairvius’ account has a more commonplace explanation: zombification. By extracting a puffer fish liver known to contain tetrodotoxin and mixing it with an unknown blend of components, a Vodou priest known as a bokor can produce an unconscious state that bears a physiological resemblance to death. To awaken the subject, a hallucinogenic substance, supposedly derived from the Datura flower, keeps the victim in a suggestable catatonia known as zombiism. Typically shown as a method of vengeance in popular entertainment, zombification has been reportedly used for slave labor in Haiti—notions explored in Jacques Tourneur’s atmospheric I Walked With a Zombie (1943) and to more pulpy effect in the Blaxploitation effort Sugar Hill (1974) and Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988). The latter film is based on a book about Clairvius Narcisse by Wade Davis, an ethnobotanist who claims to have first-hand experience witnessing zombie rituals, and whose writing constitutes a blend of scientific fact and Haitian folklore.

Bonello’s script alternates between scenes detailing the zombification experienced by Clairvius (Mackenson Bijou) in 1962 and contemporary sequences at a posh girls’ school in Paris. The latter passages involve Fanny (Louise Labèque), a member of a four-girl clique whose internal monologue details yearning love letters to her boyfriend, Pablo (Sayyid El Alami). Fanny has made friends with Mélissa (Wislanda Louimat), who moved to France from Haiti after the 2010 earthquake killed her mother, a Legion of Honor recipient for her efforts fighting dictatorship in Haiti. Fanny has invited Mélissa to apply to her privileged group’s “literary sorority”—a late-night club for drinking, sharing secrets, and holding makeshift rituals by candlelight. But Fanny’s friends think Mélissa is “weird,” from the sounds she makes at night to her general demeanor. By the looks of it, she also happens to be the only girl of color in the school. To enter their little club, Mélissa must share “something personal, something crucial.” So she recites Depestre’s poem quoted above, leaving her friends, who treat her like an outsider despite welcoming her into their inner circle, speechless, but also oblivious to its meaning.

In one of their course lectures from actual history scholar Patrick Boucheron, the professor asks his students to think about the relationship between France as a concept and a country, as a symbol of liberty and the reality that often betrays those liberties. Most of the students look aloof and disengaged at the lecture. Even if they don’t accept Boucheron’s prompt, Bonello hopes his audience will, presenting his film with two stories that unfold from the intercutting by editor Anita Roth. The narrative structure follows Boucheron’s ask to his students, without detailing France’s acquisition of Haiti from Spain in 1697, a rule that lasted until 1804—the same year Fanny’s school was founded by Napoleon. Although Boucheron teaches that France’s characteristic liberalism remains ingrained into the mythos of its national identity, his proposition encourages students to question how history has been whitewashed. Similarly, when Bonello’s nightmarish scenes of Clairvius ring with an electronic score—supplied by the musician-turned-filmmaker who often provides the music in his films—there’s a faint similarity to the synth music of George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985), both echoing and redefining the use of that distinct genre sound. It’s as though his genre music that accents Clairvius’ Vodou horror scenes represents the mythos around France, whereas the grounded images stand for historical evidence and tell another, more intricate story that goes beyond the surface.

Bonello’s interest is this interplay between actual Haitian culture and what has been appropriated by other cultures—including pop culture. After all, what happens to Clairvius is genuinely unsettling, but it’s not supernatural: He hears himself buried alive and the mourning wails at his funeral. He is awakened and forced into labor, his eyes half-shut and his body struggling in its trancelike state until he stumbles upon some cooked chicken. The food helps bring him out of his zombified hypnosis, yet he still wanders the surrounding forests, presumably for years. His scenes feed into the contemporary story, where Mélissa’s presence gives her new friends nightmares, which she perpetuates. “I am going to eat you,” she tells Fanny in a cryptic moment. After a late-night discussion about flesh-eating zombie movies, another girl dreams of Mélissa taking a bite out of her cheek. As much as they make a vague attempt to ask Mélissa about her life, her new friends are more interested in sitting on their phones or processing her culture with schlock—Fanny attempts to learn from Voodoo Possession, an exploitative found-footage zombie movie from 2014. Bonello’s contempt for their worldview is palpable. When they bond over Rihanna, the French girls admire her pop icon status, whereas Mélissa sees the musician as a symbol of pride for her ability to emerge from a Caribbean island—Barbados—and become a superstar.

Shot with crisp digital lensing by cinematographer Yves Cape (Holy Motors, 2012), the production takes on the look and feel of a horror movie. Zombi Child even manages a few scares later on, when Fanny seeks out Mélissa’s aunt, Katy (Katiana Milfort), a priestess or mambo who acts as guardian to Mélissa in Paris. Armed with a wad of cash Katy cannot ignore, Fanny wants Pablo’s spirit inside her. She insists on a ceremony, despite Katy’s protests, which unfolds at the same time as the 24th annual death ceremony for Clairvius, Katy’s father and Mélissa’s grandfather. The process, filled with a quick and dizzying exposition about the particulars, signals the fearsome arrival of Baron Samedi (Néhémy Pierre-Dahomey), who upsets Fanny’s trivial plans. Mélissa describes Baron Samedi as both a demon and god, and such duality is present throughout the film—with a white culture viewing Vodou as a source of supernatural terror, while the Haitian culture sees its many facets as “beautiful.” At the same time, the French celebrate their culture and history without considering the particulars of France’s record of violent revolutions and colonization of countries around the globe. Bonello doesn’t come out and state any of these lessons in the film, but his admiration for Haitian culture’s dimensionality is apparent. The result is a particularly circuitous and even elusive experience, albeit common for how Bonello operates as a filmmaker.

At one point in this slow-burning film, Katy explains to Fanny that Haitian culture isn’t something that can be learned by outsiders. Fanny’s conceit, propelled by that most temporary of motivations, teen love, allows her to think she can absorb Vodou with a quick web search or by skimming a Wikipedia article. But Bonello suggests it’s a process of social learning that develops over time, through a shared history. Any outsider’s view is inadequate. The horror of Zombi Child is that Fanny has attempted to appropriate Vodouism for personal reasons, prompting Baron Samedi to possess her. However, it’s less of a chilling note for Fanny than a hard-learned lesson about meddling with another culture out of entitlement—just as France too seldom looks critically at its history, as implied by Boucheron. Bonello’s final frames (set to Gerry & The Pacemakers’ “You’ll Never Walk Alone” from 1963, another in a long line of Bonello’s distinct song choices) find harmony between Mélissa and her identity as the granddaughter of a former slave, Clairvius. From their literal and symbolic sense of slavery, and from his film’s subversive relationship with horror, Bonello asks his audience to check our assumptions and look closer at our history and culture.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on June 7, 2024.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review