Zola

By Brian Eggert |

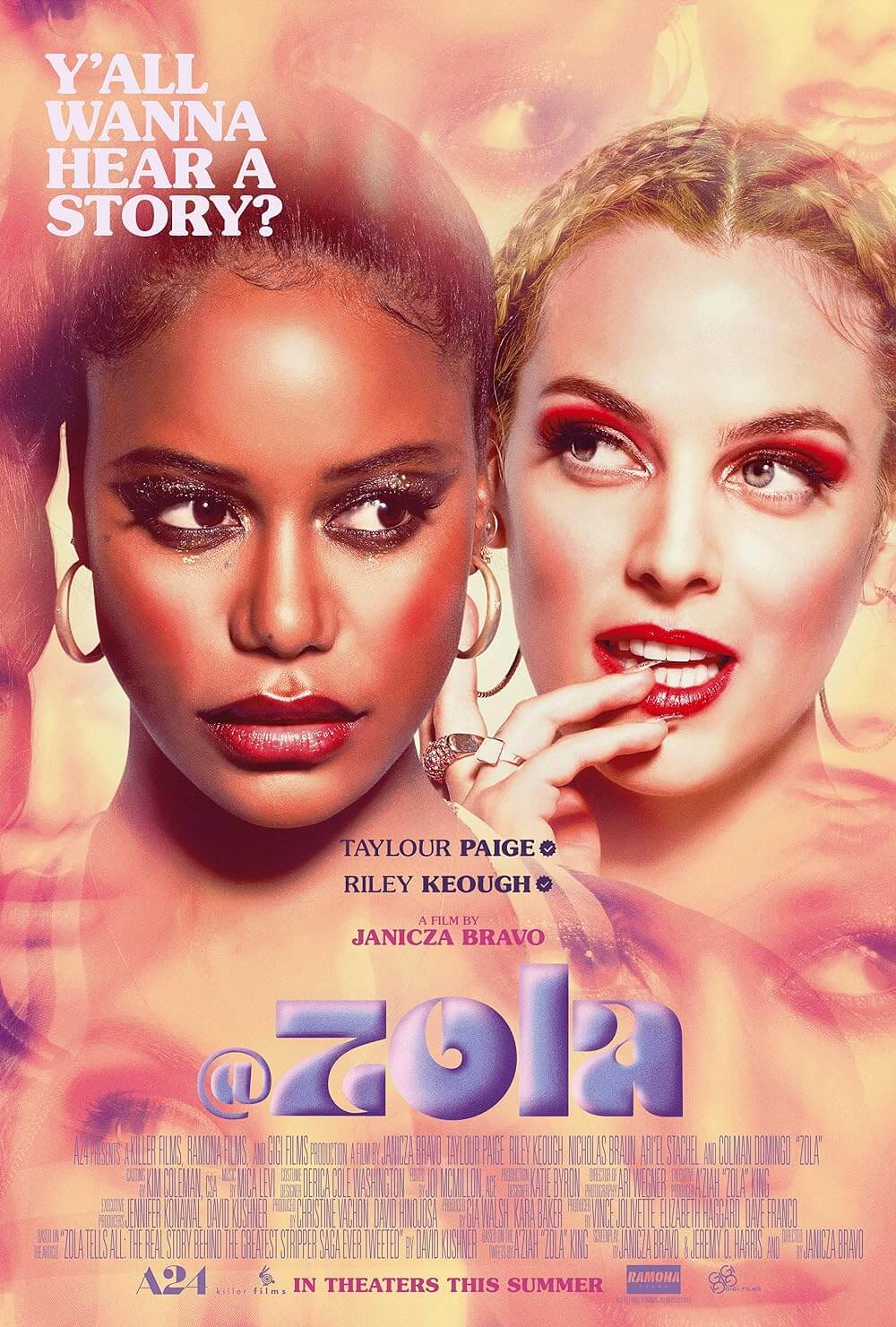

“Y’all wanna hear a story about why me and this bitch here fell out???????? It’s kind of long but full of suspense.” That’s how A’Ziah “Zola” King, an exotic dancer from Detroit, started her dizzying, unbelievable, sometimes hilarious, and often terrifying 148-tweet thread on Twitter in 2015. Then it went viral. Then Rolling Stone published an article, “Zola Tells All: The Real Story Behind the Greatest Stripper Saga Ever Tweeted,” in which David Kushner summarized the tale with journalistic flair. Then writer-director Janicza Bravo turned Kushner’s account into her second feature film, aptly named Zola, which played at the Sundance Film Festival in 2020. Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the film’s release was delayed. Then, after theaters started opening up, A24 finally released it. And after watching the film, you’ll feel exhausted from its insane rollercoaster ride—a crazy weekend trip to Florida filled with unpredictable characters and bizarro turns, yet a disarming sense of humor about itself.

It plays like Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild (1986), where a dodgy set of circumstances gradually twists into a nightmare. But also, somehow, there’s a lightness that could be mistaken for fun. After all, we know Zola survived the ordeal since she tweeted about it. What is more, the distancing effect of cinema gives us perspective on the whole, unsavory series of events. Taylour Paige plays Zola, who regularly quotes the real Zola’s tweets in her dialogue and narration—each one signaled by Twitter’s notification chirp. While serving tables at a Hooters-like restaurant, Zola meets Stefani (Riley Keough), who’s there with one of her sugar daddies. The two bond over their mutual “hoeism” and, the next day, make plans for a “ho trip” to Tampa to earn big from pole dancing. However, Zola soon realizes the two men who accompany them, Derrek (Nicholas Braun) and the yet-unnamed X (Colman Domingo), are Stefani’s boyfriend and pimp, respectively. Later, she discovers Stefani has manipulated her into enlisting as a sex worker for X, a volatile and intimidating man whose American accent drops in his fits of rage.

What happens from moment to moment is somewhat less compelling than how Bravo and her excellent cast convey it. Paige plays the resident straight woman in a farcical comedy of errors, her performance shaped by her priceless deadpan reactions and expressive eyes that give so much with a roll or squint. It’s an understated, controlled performance that threatens to be overlooked by the two flashier, uninhibited, larger-than-life turns by Keough and Domingo. The former has played ferocious and awful people before (see American Honey, 2016), but never with such bombast, complete with an affected, appropriative accent; garish wardrobe; and crazy-ass behavior. As Zola tells her new so-called friend: “This is messy. You’re messy. Your brain is broke.” But if you want to get to the root of the difference between Zola and Stefani, it can be summed up in a public restroom scene. Stefani sits directly on the seat; Zola hovers just above it. Indeed, bathroom habits say a lot about people in this film. Domingo, who hasn’t had such a significant and memorable role outside of AMC’s Fear the Walking Dead, plays a guy who clears his throat constantly when he urinates, which he always does with the door open. He’s posturing, dangerous, and predatory—it’s a show-stealing performance, and he’s genuinely chilling at times.

Only the internet could have given birth to Zola’s story, and Bravo’s aesthetic here reflects the internet’s structure, overstimulation, and desperate need for attention. The real Zola littered her thread with emojis, all caps, and multiple exclamation points. Bravo captures the cinematic equivalent with flashy camerawork, smartphone-shot scenes, zippy transitions, and occasional detours away from Zola’s narration, which stops just short of breaking the fourth wall. “From here on out,” she tells us early on after a Goodfellas-style freeze-frame, “Watch every move this bitch makes.” And between the strippers and Scorsese reference, Zola cannot help but recall Hustlers (2019), a film that actively resisted the male gaze. Bravo is less concerned with that. Her frame maneuvers around Zola’s pole routine, and she doesn’t mind the occasional ogle. But the approach captures the voyeuristic nature of the internet. Watch the montage of sex between Stefani and a string of several men, how it unfolds as though the viewer were flipping through posts on Instagram. One image is just as disposable, lurid, and consumable as the next, captured with a hollowness that perfectly reflects the online experience.

Only the internet could have given birth to Zola’s story, and Bravo’s aesthetic here reflects the internet’s structure, overstimulation, and desperate need for attention. The real Zola littered her thread with emojis, all caps, and multiple exclamation points. Bravo captures the cinematic equivalent with flashy camerawork, smartphone-shot scenes, zippy transitions, and occasional detours away from Zola’s narration, which stops just short of breaking the fourth wall. “From here on out,” she tells us early on after a Goodfellas-style freeze-frame, “Watch every move this bitch makes.” And between the strippers and Scorsese reference, Zola cannot help but recall Hustlers (2019), a film that actively resisted the male gaze. Bravo is less concerned with that. Her frame maneuvers around Zola’s pole routine, and she doesn’t mind the occasional ogle. But the approach captures the voyeuristic nature of the internet. Watch the montage of sex between Stefani and a string of several men, how it unfolds as though the viewer were flipping through posts on Instagram. One image is just as disposable, lurid, and consumable as the next, captured with a hollowness that perfectly reflects the online experience.

There’s plenty of room here to turn Zola into a socially responsible film that gives everything onscreen greater meaning. Bravo and her co-writer Jeremy O. Harris, playwright of the Tony-nominated Slave Play, could have easily used this scenario to talk about sexual labor, white appropriation of Black culture, or ultimately the threat of sex trafficking in America. Bravo’s first effort, Lemon (2017), set out to critique a particular breed of self-satisfied white male through ridiculous comic situations. By contrast, Zola fearlessly refuses to find some lofty artistic raison d’être and remains true to Zola’s original thread. But it does make some curious changes, such as omitting that X—dubbed Z in the thread, just one of the many name changes in the film—went to jail for murder and trafficking. The film ends rather abruptly, leaving the real-life aftermath up to the audience to discover. Including X’s fate could have brought the film more closure. Then again, Bravo seems more interested in replicating the fascinating trainwreck of Zola’s tweets, delighting in her gloriously uninhibited slang and energy. Through it, she delivers an exercise in translating social media to the cinema. One scene shows Zola preparing in the mirror before a stage performance, asking herself, “Who are you gonna be tonight, Zola?” Bravo shows us how the internet is a stage of masks, performance, rants, desire, exploitation, and gaslighting—all wrapped up in a beguiling whole.

Bravo doesn’t tell the viewer how we should feel about the proceedings. She’s not out to make a commentary about the internet primarily, nor does she judge the people who live a significant portion of their lives through social media. Consuming Zola, it’s unclear if we should feel disgusted, saddened, amused, alarmed, or bewildered. The answer is all of the above. Finally, though, we may judge for ourselves the people who inhabit these worlds. And viewers looking for a clue about how to feel about these events should listen to the superb music by Mica Levy, whose scores for Under the Skin (2013) and Jackie (2016) remain among this century’s best. As Zola roams Florida with Stefani and company from a dingy motel to a shady club, from a cheap hotel to X’s extravagant Florida beach house, Levy sets the tone with an ominous beat, on top of which are electronic chime swipes. It’s as though she pulls back the curtain on a surreal world that’s dreamlike and nightmarish, hilarious and horrifying, entertaining and disturbing. And that perfectly captures the essence of Zola.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review