Zack Snyder’s Justice League

By Brian Eggert |

Zack Snyder’s initial vision for Justice League—and then some—finally arrives under a strange set of circumstances, three years after the film’s theatrical release underwhelmed critically and commercially. Now called Zack Snyder’s Justice League, the film debuts on HBOMax, representing a victory for the pestering fanbase that demanded an alternate take on the disappointing, and occasionally embarrassing, 2017 version, reworked by an uncredited Joss Whedon. Snyder’s new Justice League is a product of indulgences: It indulges the relentless toxic fan culture, which clamored and complained and whined until they got what they wanted. It allows Snyder to indulge his artistic impulses, insert his unused original footage, and create some newly shot material to assemble a four-hour-and-two-minute runtime. And it also indulges Snyder’s idiosyncratic technical and narrative structural choices, which feel ill-suited for either at-home viewing or theatrical exhibition. Altogether, it’s admirable in some facets and downright frustrating in others. The “Snyder Cut” happened, and it’s a weird success story for fans, even while the experience of watching it remains a mixed bag of improvements, curiosities, pleasures, irregularities, and emptiness. Neither an overwhelming artistic victory nor a complete failure, the entire thing is an oddity and certainly unprecedented.

For the uninitiated, Snyder has been working on DC superhero movies at Warner Bros. for over a decade. He helped launch the so-called DC Extended Universe with 2013’s disappointing Man of Steel, followed by 2016’s Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice. Other filmmakers introduced heroes in Suicide Squad (2016), Wonder Woman (2017), Aquaman (2018), Shazam! (2019), Birds of Prey (2020), and Wonder Woman 1984 (2020)—though the overall results have been uneven. The franchise tried to replicate the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s synergy, but Warners failed to regulate quality or create a narrative throughline over the nine movies released thus far. Justice League was meant to be an Avengers-like crossover epic. During the production, the studio was unhappy with his oversight of the DCEU and brooding take on the characters. When Snyder had to leave the production after a family tragedy, they opted to hire another filmmaker who would go the direction they wanted. Enter Joss Whedon, who oversaw expensive reshoots and delivered a product that dramatically altered Snyder’s vision. Between the goofy CGI removal of Henry Cavill’s mustache, the movie’s striking resemblance to Whedon’s The Avengers, and the reports of Whedon’s abusive behavior on the set, the movie was a hollow and marred experience.

Not long after the 2017 debut of Whedon’s version, voices on social media made their demands: #ReleaseTheSnyderCut. For years, the persistent voices went unheard until HBO, a division of WarnerMedia, launched its new subscription service, HBOMax. In a bid for exclusive content that would attract new subscribers, Warner Bros. agreed to give Snyder another $70 million to complete additional footage, redo some special FX, and deliver his indulgent hunk of superhero moviemaking. And so, the fans who complained to a major Hollywood studio can now log onto their subscription streaming service and watch all four hours of Snyder’s new version, the result of several years of production time, well over $500 million in estimated budget and marketing costs, and some off-screen scandals that have ruined careers. When I sit down to watch Zack Snyder’s Justice League, I ask myself, Is this film worth all the time, money, and heartache? It’s an improvement, to be sure. But it’s far from a triumph.

Not long after the 2017 debut of Whedon’s version, voices on social media made their demands: #ReleaseTheSnyderCut. For years, the persistent voices went unheard until HBO, a division of WarnerMedia, launched its new subscription service, HBOMax. In a bid for exclusive content that would attract new subscribers, Warner Bros. agreed to give Snyder another $70 million to complete additional footage, redo some special FX, and deliver his indulgent hunk of superhero moviemaking. And so, the fans who complained to a major Hollywood studio can now log onto their subscription streaming service and watch all four hours of Snyder’s new version, the result of several years of production time, well over $500 million in estimated budget and marketing costs, and some off-screen scandals that have ruined careers. When I sit down to watch Zack Snyder’s Justice League, I ask myself, Is this film worth all the time, money, and heartache? It’s an improvement, to be sure. But it’s far from a triumph.

If you saw Whedon’s version, the same basic story remains intact and continues to bear an uncanny resemblance to The Avengers: We follow a disgraced alien conqueror, Steppenwolf (Ciarán Hinds, his face and voice digitally altered), who wants to get his hands on three Mother Boxes (like Infinity Stones, Horcruxes, One Ring to Rule Them All, etc.). When combined, the advanced technology will allow him to claim Earth for his master, Darkseid—the universe’s godlike despot, a personality-less version of Thanos bent on acquiring a formula for “anti-life.” A flashback shows that Darkseid once tried to conquer Earth, except the so-called Old Gods thwarted him. Sometime in the last few millennia, Darkseid apparently forgot not only his one-and-only defeat but that his precious “anti-life” recipe was stored on Earth, and so he’s been scouring the multiverse ever since in search of it. Plot holes aside, Steppenwolf establishes an evil lair inside an irradiated nuclear reactor (“It’s toxic. That’s good,” he proclaims in the film’s typically dull dialogue) and hunts down the three Mother Boxes needed to complete his Master Plan. Alerted to the plan, Bruce Wayne, aka Batman (Ben Affleck, solid), sets out to assemble a team of heroes to stop the world-dominating alien threat. After enlisting Wonder Woman (Gal Godot), Aquaman (Jason Momoa), The Flash (Ezra Miller), and Cyborg (Ray Fisher), the team plans to revive Superman (Henry Cavill), who died at the end of Dawn of Justice, since he’s the only hero capable of defeating Steppenwolf.

Now let’s consider what Snyder has brought to the proceedings with two additional hours of screen time. For starters, he organizes the film in several chapters with titles like “Don’t Count on It, Batman” and “The Age of Heroes,” perhaps as remnants of HBO’s original intention to have Snyder’s version unfold like episodic television. Each of his characters’ backstories now has room to breathe, though in most cases, the additions feel like excuses to show his heroes brooding, usually in the director’s beloved slow-motion. Batman and Wonder Woman’s storylines remain mostly the same, as Whedon included most of their footage in the theatrical cut. The Flash and Aquaman have a few perfunctory character moments—the former is saddled with unfunny comic relief fare, the latter sulks about in his undersea Atlantis. Neither receives sufficient depth, leaving us with questions about how Flash got his powers or about the nature of Aquaman’s beef with Atlantians. And all of these heroes have issues with their parents—some disapproving, some in jail, and many dead, leading to numerous scenes of standing over gravestones.

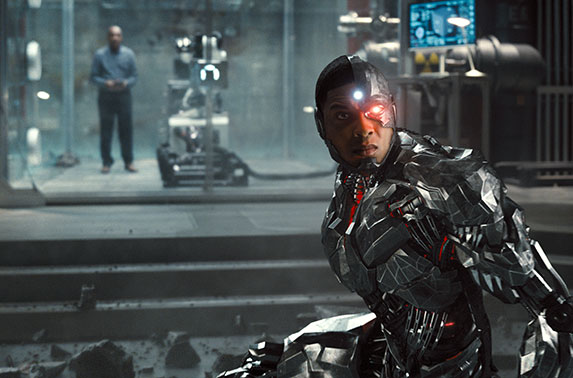

The most significant additions belong to Cyborg, whose dramatic arc was almost nonexistent in Whedon’s cut. Cyborg’s rocky relationship with his father, Silas Stone (Joe Morton), the Starlabs scientist who turned his son into a cybernetic being after a car accident, shapes the character. Silas imbued his son with the ability to overcome any firewall, move funds from one bank account to another at will, and launch the world’s nuclear arsenal with a few thoughts. Silas explains that his son’s challenge is not using those powers, which seems like a risky gamble on a disgruntled young man (especially from Morton, who once played the inventor of SkyNet). All of this power seems useless, however, when Cyborg loses control of his auto-defense system and shoots a missile at the resurrected, temporarily hostile Superman. This is the guy you want in charge of the nuclear arsenal? In any case, Cyborg’s knack for computers allows him to hack the Mother Boxes later in the movie, completing his arc. Additionally, several scenes are devoted to a sub-subplot about Cyborg’s unique relationship with technology that allows him to fix Batman’s carrier jet—and they belonged on the cutting room floor. Given Cyborg’s additional scenes, along with a flurry of new cameos (including an appearance by Jared Leto’s tiresome Joker), the film’s fans will be poring over plot minutiae for hours.

The most significant additions belong to Cyborg, whose dramatic arc was almost nonexistent in Whedon’s cut. Cyborg’s rocky relationship with his father, Silas Stone (Joe Morton), the Starlabs scientist who turned his son into a cybernetic being after a car accident, shapes the character. Silas imbued his son with the ability to overcome any firewall, move funds from one bank account to another at will, and launch the world’s nuclear arsenal with a few thoughts. Silas explains that his son’s challenge is not using those powers, which seems like a risky gamble on a disgruntled young man (especially from Morton, who once played the inventor of SkyNet). All of this power seems useless, however, when Cyborg loses control of his auto-defense system and shoots a missile at the resurrected, temporarily hostile Superman. This is the guy you want in charge of the nuclear arsenal? In any case, Cyborg’s knack for computers allows him to hack the Mother Boxes later in the movie, completing his arc. Additionally, several scenes are devoted to a sub-subplot about Cyborg’s unique relationship with technology that allows him to fix Batman’s carrier jet—and they belonged on the cutting room floor. Given Cyborg’s additional scenes, along with a flurry of new cameos (including an appearance by Jared Leto’s tiresome Joker), the film’s fans will be poring over plot minutiae for hours.

If the story’s referenced inconsistencies are any indication, not everything works about Snyder’s new cut; there’s just more of it. His particular aesthetic tends to make everything feel grandiose, accented by iconic slow-mo—often beautiful imagery that underscores the godly, larger-than-life nature of DC heroes. And while Snyder’s approach wears a viewer down when there’s a traditional runtime, this 242-minute behemoth amplifies the quality, doubling it. Every action scene turns into a series of bullet-time-style sequences interrupted, briefly, by hyper action that reveals the lightspeed reality of the fights. It’s a familiar tactic for the director, evident in his work since his 2004 debut Dawn of the Dead, complete with a fetish for empty gun shells dropping to the ground at a funeral’s pace. We cannot help but wonder how many minutes we could have been spared had Snyder limited his uses of slow-mo by half. My guess would be fifteen, at least. But no matter how often he employs lingering shots with visual luster, the film cannot escape Chris Terrio’s largely humorless screenplay.

Snyder’s imagery may make his superheroes appear legendary, but the characterizations prove unrelatable and inaccessible. Snyder has made them into icons more than flesh-and-blood characters. Sure, The Flash’s amusing moment of concern when he realizes Superman can keep up remains comically intact, and Bruce Wayne’s confession that his superpower is wealth proves amusing. On the emotional spectrum’s other end, the downer scenes of Lois Lane mourning Superman look appropriately weighty, even though they give Amy Adams little to do. It’s easy to forget that her character was originally written as the ultimate strong-willed, go-getter reporter. Now she’s a shell with an unused pregnancy test in her bedside table. These flourishes aside, there’s nary a moment of genuine emotion or comic relief—and relief from Snyder’s oppressive, laborious visual style is just what’s needed.

Oddly, Snyder chose a boxier aspect ratio in hopes of exhibiting his version of Justice League on IMAX screens. Although the “Snyder Cut” was designed for home viewing, Snyder’s choice robs the viewer of almost a third of their television screen by narrowing cinematographer Fabian Wagner’s images. Occasionally, a character bleeds outside of the frame, evidently cropped out, and we’re left wondering about the utility of this decision. After all, the director had a rare opportunity to give this project new life on HBOMax thanks to his fanbase’s demands. The four-hour cut would be an unlikely, or at least ill-advised, choice for wide theatrical distribution. Knowing that his monumentally sized film would premiere on widescreen-standard televisions, he rejected a form-follows-function solution. He chose an aspect ratio designated for theatrical exhibition—and not even standard exhibition, but a niche found in just a few hundred theaters worldwide. You might call it looking a gift horse in the mouth. He delivers a product that, for four hours, reminds fans who demanded to see the “Snyder Cut” that they’re not seeing everything they could be, and what’s more, they’re forced to watch it at home rather than in the theater. It can’t help but feel like a qualified victory.

Oddly, Snyder chose a boxier aspect ratio in hopes of exhibiting his version of Justice League on IMAX screens. Although the “Snyder Cut” was designed for home viewing, Snyder’s choice robs the viewer of almost a third of their television screen by narrowing cinematographer Fabian Wagner’s images. Occasionally, a character bleeds outside of the frame, evidently cropped out, and we’re left wondering about the utility of this decision. After all, the director had a rare opportunity to give this project new life on HBOMax thanks to his fanbase’s demands. The four-hour cut would be an unlikely, or at least ill-advised, choice for wide theatrical distribution. Knowing that his monumentally sized film would premiere on widescreen-standard televisions, he rejected a form-follows-function solution. He chose an aspect ratio designated for theatrical exhibition—and not even standard exhibition, but a niche found in just a few hundred theaters worldwide. You might call it looking a gift horse in the mouth. He delivers a product that, for four hours, reminds fans who demanded to see the “Snyder Cut” that they’re not seeing everything they could be, and what’s more, they’re forced to watch it at home rather than in the theater. It can’t help but feel like a qualified victory.

Somehow, Justice League is the most for-the-fans movie of recent memory, even while some of Snyder’s choices nag at the viewer throughout (let’s just ignore how this version contains open-ended storylines, most of them introduced in the half-hour epilogue, that will probably never be resolved in Warners’ flailing DCEU). Then again, the point, I suppose, is that Snyder’s project got released in the manner he wanted. It improves upon Whedon’s slapdash version from 2017, resulting in a work of visual and tonal consistency—a cohesive vision. But that doesn’t make Snyder’s version a masterpiece. It’s simply a longer and more palatable movie. The film creates new problems even as it solves old ones, such as how the length does the material a disservice, emphasizing Snyder’s style-as-substance touch. The extended runtime gives the viewer’s mind room to wander and consider the surface-level personalities on display. And while restraint has never been one of Snyder’s strong suits, the consequence of his remarkable opportunity with HBOMax is self-indulgent, overlong, and ultimately just the midsection of a larger story that may never get completed onscreen. Snyder devotees will be pleased, but Zack Snyder’s Justice League cannot help but feel somehow incomplete.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review