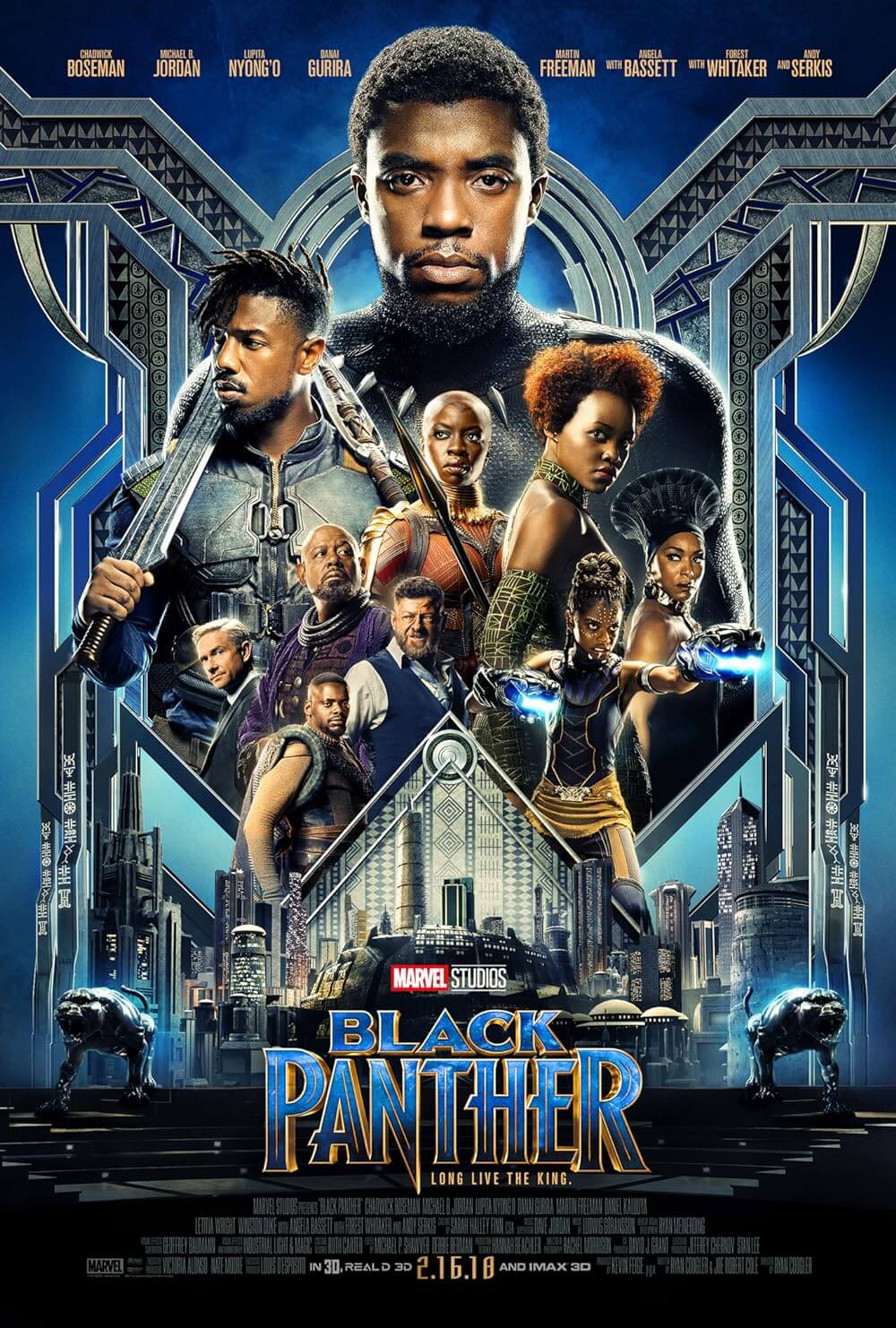

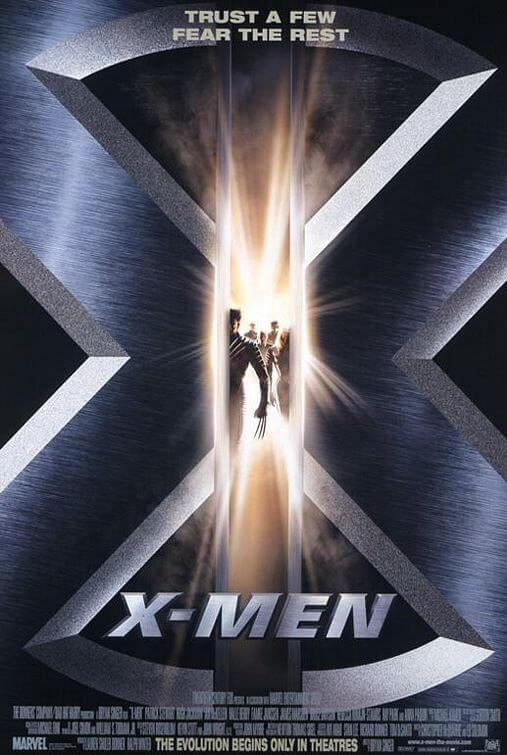

X-Men

By Brian Eggert |

Throughout the 1990s, the comic book scene was dominated by Marvel Comics’ X-Men, a massive team of superheroes that inspired an expansive franchise, which has still barely reached the scope of its possibility. A popular animated series and toy line followed and proved its marketability beyond the printed page, because the ongoing story concerned overcoming adversity and addressed important social concerns. Much of my own adolescence was spent with my nose in the pages of The Uncanny X-Men or Wolverine, reading the adventures and romances of my favorite mutant-powered heroes. Often, I would daydream of a movie, speculate as to the model story for the film, and wonder how Hollywood could ever get it right. Bryan Singer’s film of X-Men comes pretty damn close to those adolescent dreams of mine, succeeding in terms of casting, beginning a long-running and popular motion picture series, as well as (re)proving the validity of superhero movies to the world cinema market.

Made in 2000, before I ever considered film criticism, my enthusiasm toward the film then was perhaps overblown. The comic book aficionado and apologist in me believed the adaptation was faithful, whereas the critic seedling barely grasped its flaws. Now things are clearer. So while the film is still a complete joy, some Hollywoodized aspects are best ignored. On page and film, the story of the X-Men begins when genetic mutations reveal themselves during adolescence and manifest in the form of superpowers. Professor Charles Xavier (Patrick Stewart), a powerful psychic, runs a school to help “gifted youngsters” control their newfound abilities—everything from telekinesis to place-to-place teleportation. The world believes mutants should be regulated by the government, inspiring Xavier to form the X-Men, a group of his students determined to fight for adversity. Their missions help protect mutants from the public, and vice versa, to better human-mutant relations. But Xavier’s friend-turned-villain Magneto (Ian McKellen), a mutant with the power to control metal by way of magnetism, believes mutants are the next evolutionary step up, and he intends to usher them to their rightful place at the top of the world’s food chain.

And that’s about how the film plays out, with the sympathetic yet misguided Magneto attempting to convince world leaders of the mutant perspective by turning them into mutants themselves. The conflict concerns Senator Kelly (Bruce Davison), whose plan is The Mutant Registration Act, which would catalog mutants of the world and force them to expose themselves, in turn spearheading a new form of genetic racism. Having experienced the regimentation of a race as a child during the Holocaust, Magneto, given all the weight and sympathy and gravitas McKellen can offer, now has the power to prevent genocide from occurring again. Cue the X-Men to stop him. But doesn’t Magneto’s plan make sense? Shouldn’t mutants defend themselves against a threat so totalitarian if they can? Indeed, should Darwinism apply, mutants would have little trouble conquering the planet in this fictional universe. And yet, Xavier believes in a peaceful coexistence between humans and mutants, an idealized dream that in the comics and the film is likely never possible. For this reason, the comic and the film succeed in being more than your average superhero yarn. The landscape is wrought with human protesters and villains often wanting to protect themselves. Every reader or viewer can identify with the fear of bigotry presented, and whether they’re on the giving or receiving end, the narrative boasts an admirable message of equality. There are potent motives behind every character, and the actionized plot resembles a morality play more than typical good vs. evil superhero fluff.

Beginning with the cast, Singer’s choices couldn’t be better. Stewart as Xavier offers a twofer for fans of both the comic and Star Trek: The Next Generation, as the bald-headed performer seems perfect for the wheelchair-bound, likewise coiffured character. McKellen is another thespian to equal Stewart. Then-newcomer Hugh Jackman plays Wolverine, everyone’s favorite bad-boy hero with advanced healing powers, adamantium claws, a nasty case of amnesia, and an attitude to boot. Jackman is wonderful in the role, which serves as the heart of the story, and the centerpiece for subsequent sequels, including his own solo movies. For the team of X-Men, their leader, Cyclops, who shoots energy blasts from his eyes, is played with necessary straightforwardness by young actor James Marsden. His telekinetic sweetheart, Jean Grey, is played by Famke Janssen. The “untouchable” power-stealing youngster is Rogue, changed for the film and rendered your average teenager, played by Anna Paquin. The weather-controlling Storm is Halle Berry, who looks the part despite her poor pseudo-African accent.

From the standpoint of a comic reader, some of the production’s changes to character origin and appearance prove distressing, particularly with Magneto’s gang of villains. Consider the “sexiness” of Mystique, played by model Rebecca Romijn (then-Stamos), a shape-shifting character whose white dress is replaced by scales, gallons of blue body paint, and near-nakedness. Toad (Ray Park) is also painted, but he’s green and given a ridiculously long tongue, which comic readers scratched their heads over. And the biggest faux pas was Sabretooth (Tyler Mane), whose almost silent role lacks any potential for Wolverine to explore his relationship with his archnemesis further. But besides these quibbles, the film gets it right, for the most part, to satisfactory degrees.

Having helmed both The Usual Suspects and Apt Pupil prior, Singer’s direction contains the same sharp eye and concentration on visual compositions as the characters. He worked closely with screenwriter David Hayter (Watchmen) to faithfully grasp the multitude of characters and conflicts present in the X-Men universe. Missteps do occur, such as the over-glorified final battle atop the Statue of Liberty and the awkward dismissal of Sabretooth via uneventful death. Or consider the useless dialogue when Storm and Toad battle: “Do you know what happens to a toad when it’s struck by lightning? The same thing that happens to everything else.” Well, duh!

Where Singer thrives is his balance of the comic and filmic worlds, making the characters full of melodramatic conflict to enhance the comic-book nature of the storyline. The comics featured a community of mutants broken up into several teams; including X-Men, The Uncanny X-Men, X-Factor, X-Force, Excalibur, and The New Mutants. Indeed, the initial comic from 1963 spawned uncountable characters and storylines no single film could cover. And while some fans may balk that their favorite hero (Gambit or Beast or Angel) or villain (Apocalypse or Mr. Sinister or the Sentinels) didn’t appear in this first film, with any luck, they’ll appear in a future sequel or spinoff in some capacity. Comic fans should keep their eye on the background, as Singer cares for this segment of the audience, and makes references to future plots or important characters, if indirectly. He cares equally about comic fans and filmgoers unfamiliar with the material, and though he occasionally tries too hard to comfort the average viewer, the resulting film proves an entertaining and appeasing effort.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review