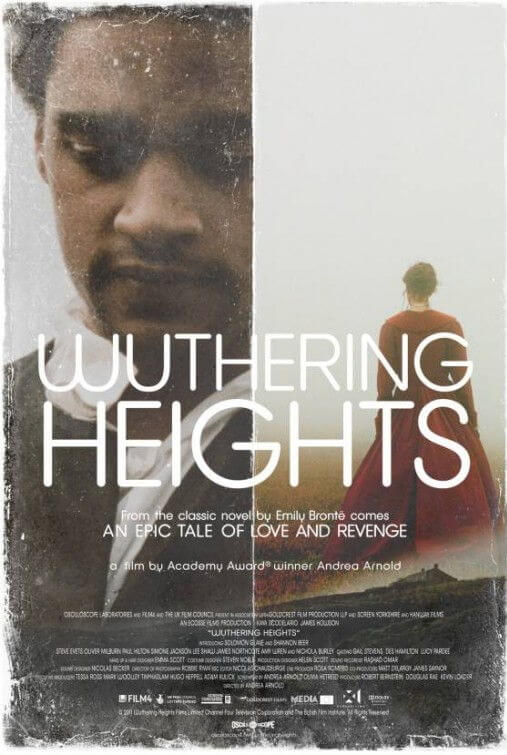

Wuthering Heights

By Brian Eggert |

All the superficial embellishments typically linked to classicized costume dramas have been stripped away in director Andrea Arnold’s raw, spare adaptation of Wuthering Heights. Avoided are the prestigious and regal reputation of Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel and its long-established tradition of elegant interpretations on the screen, enjoyable to behold though they may be—particularly William Wyler’s 1939 version starring Laurence Olivier as Heathcliff and Merle Oberon as Cathy. Arnold’s take replaces romanticism with unrefined emotion, angry and powerful, though also achingly complex, in the same way that Nature is simple yet intricate. It’s a dark and unlikable film that must be admired for Arnold’s dedication to her task: Interpret the source material in such a way that it feels new and reinvigorated. That said, Arnold creates a radically desolate piece of cinema that presents a challenge to traditionalist audiences.

The revised story begins on the Yorkshire moors, where Mr. Earnshaw (Paul Hilton) brings the young Heathcliff, here played by black actor Solomon Glave (and later as a twentysomething man by James Howson). With Arnold’s innovative description of Heathcliff, his outsider status is set by the color of his skin and the Earnshaws’ intolerance. Heathcliff nonetheless forms a bond with Mr. Earnshaw’s daughter Cathy (Shannon Beer), and together the two explore the surrounding moors and, as implied, each other. When Mr. Earnshaw dies, his bitter son Hindley (Lee Shaw) becomes the farm’s prevailing Master and unleashes abuses on Heathcliff, who, barred from talking to Cathy, watches as she’s courted by a “respectable” suitor. At this, Heathcliff leaves heartbroken, returning years later now inexplicably well-to-do and hungry for revenge on Hindley, and to present himself to the now-married and with child Cathy (the older version played by Kaya Scodelario).

Arnold’s minimalist approach is presented in a pan & scan aspect ratio, using grainy handheld lensing by Robbie Ryan and interspersed with unique angles and jarring jump-cuts. The presentation is almost devoid of non-diegetic music, save for an ungainly tune in the finale played by Mumford & Sons, effectively taking us out of the period in which Arnold tries so unrelentingly to immerse us. Every element of Arnold’s technical approach dissolves the romanticism and heightens the emotional significance by embracing a notably unromantic, arguably more historically genuine setting. Natural lighting is used throughout, making night scenes often dark to the point of unintelligibility. Recurring shots of moor wildlife—birds, beetles, landscapes—emphasize the thematic distinction between civilization and the wild, yet these shots also feel repetitive. Unpressed clothes looked soiled by the purveying mud of the moorlands, where it’s especially unhealthy to be a rabbit, bird, or even a dog.

Indeed, along with Heathcliff killing animals to feed the Earnshaws, at least two dogs are hung from the neck, either to quiet his rage or simply because it’s one too many mouths to feed. If there’s anything a filmmaker could do to place a barrier between her audience and the emotional lows of her protagonist, it’s killing a dog (Movie rule: never kill the dog), even if such animal cruelty is referenced in Brontë’s text. Slightly less disturbing, believe it or not, is a moment of necrophilia. But then Arnold isn’t one to play by the rules. She continuously explores uncomfortable emotions and situations. In her two previous and equally confrontational efforts, Red Road (2006) and Fish Tank (2010), her female protagonists, for one reason or another, each picks an odd choice of man that results in a jarring offense to the viewer. Wuthering Heights is about confronting the audience with their expectations for a Brontë tale.

Harsh domestic and environmental circumstances give way to a general feeling of emotional immediacy amid the ugliness about everything onscreen (though, admittedly, Ryan’s occasional impressionist views of the foggy, pastel landscape are gorgeous). Cussing and violence, spitting in each other’s faces, Heathcliff’s penchant for slamming his head against trees and walls—in place of the film’s deafening lack of dialogue, these are the ways Arnold’s characters communicate. We’ve grown accustomed to romanticized stories of forlorn love, and all the associated decorative rooms and polished silverware. Period pieces are put on lofty airs because it is tradition, and Arnold does the opposite but, curiously, achieves the same effect through a different kind of expressive quality. The film’s drives toward authenticity and naturalism have their own mannerisms, and they’re splendidly used here, even if they’re not what we might consider “pleasant” or “enjoyable.” No one said good art must be an agreeable experience.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review