Wrath of Man

By Brian Eggert |

Half of director Guy Ritchie’s output has been crime comedies; the other half has been studio tentpoles with varying degrees of soullessness. Mention Ritchie’s name, and it brings to mind a hyper-energetic, often funny, post-Tarantino mode of British crime cinema. But his reputation has rested on the greatness of Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels (1998), Snatch (2000), and RocknRolla (2008) for years. Over the last decade, Ritchie has busied himself with blockbuster intellectual properties. Some, like the Robert Downey Jr. starring Sherlock Holmes (2009) and its sequel, integrated Ritchie’s penchant for gleefully seedy characters, zippy editing, and flashy aesthetics into a period film. Others include the airless King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017) and his abysmal live-action take on Disney’s Aladdin (2019). Only last year did Ritchie return to British crime in the manner of his former heights with The Gentlemen, which felt like Ritchie imitating himself. In point of fact, Ritchie has spent more time working outside of the genre that often defines him than he does within it.

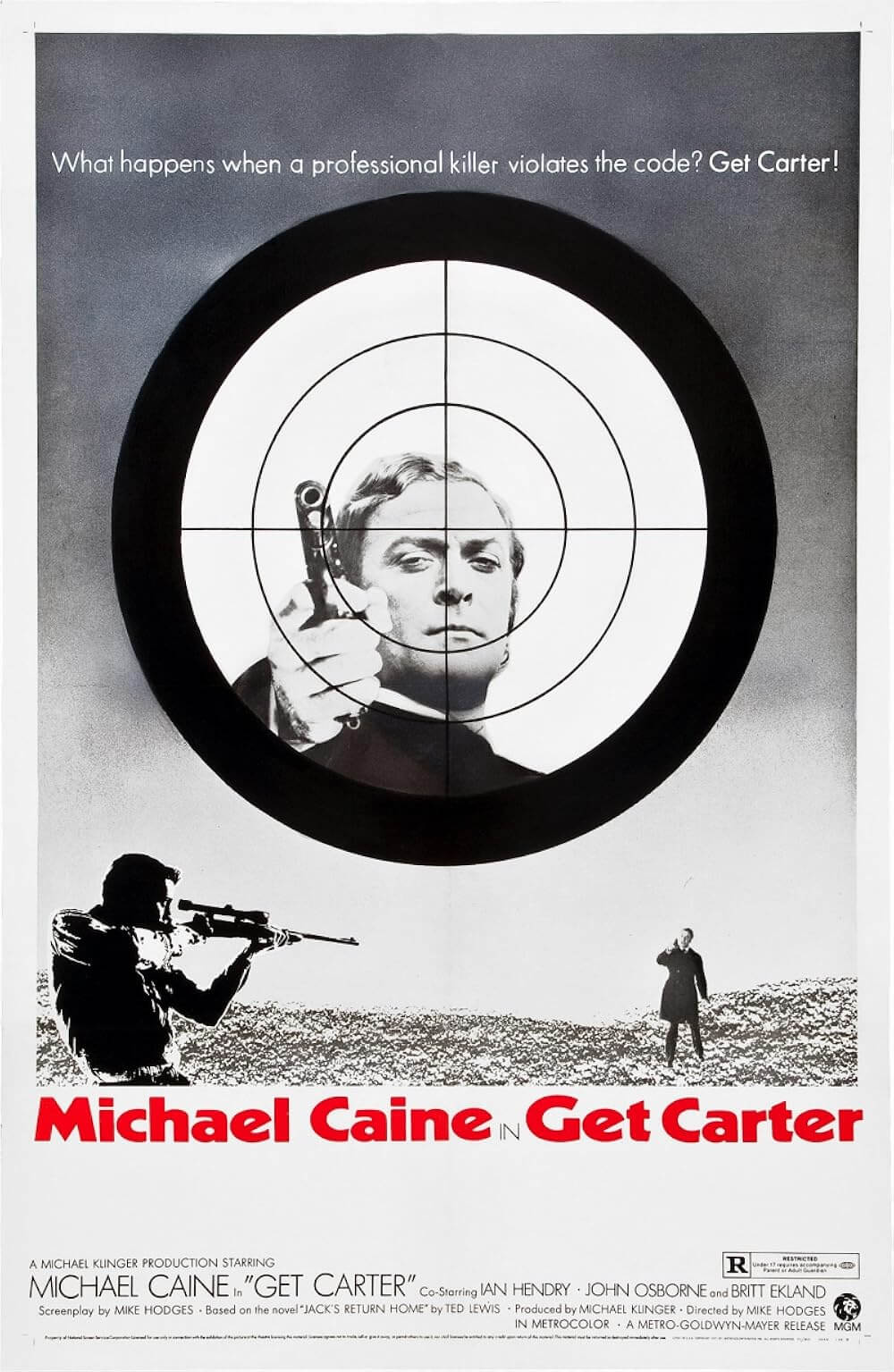

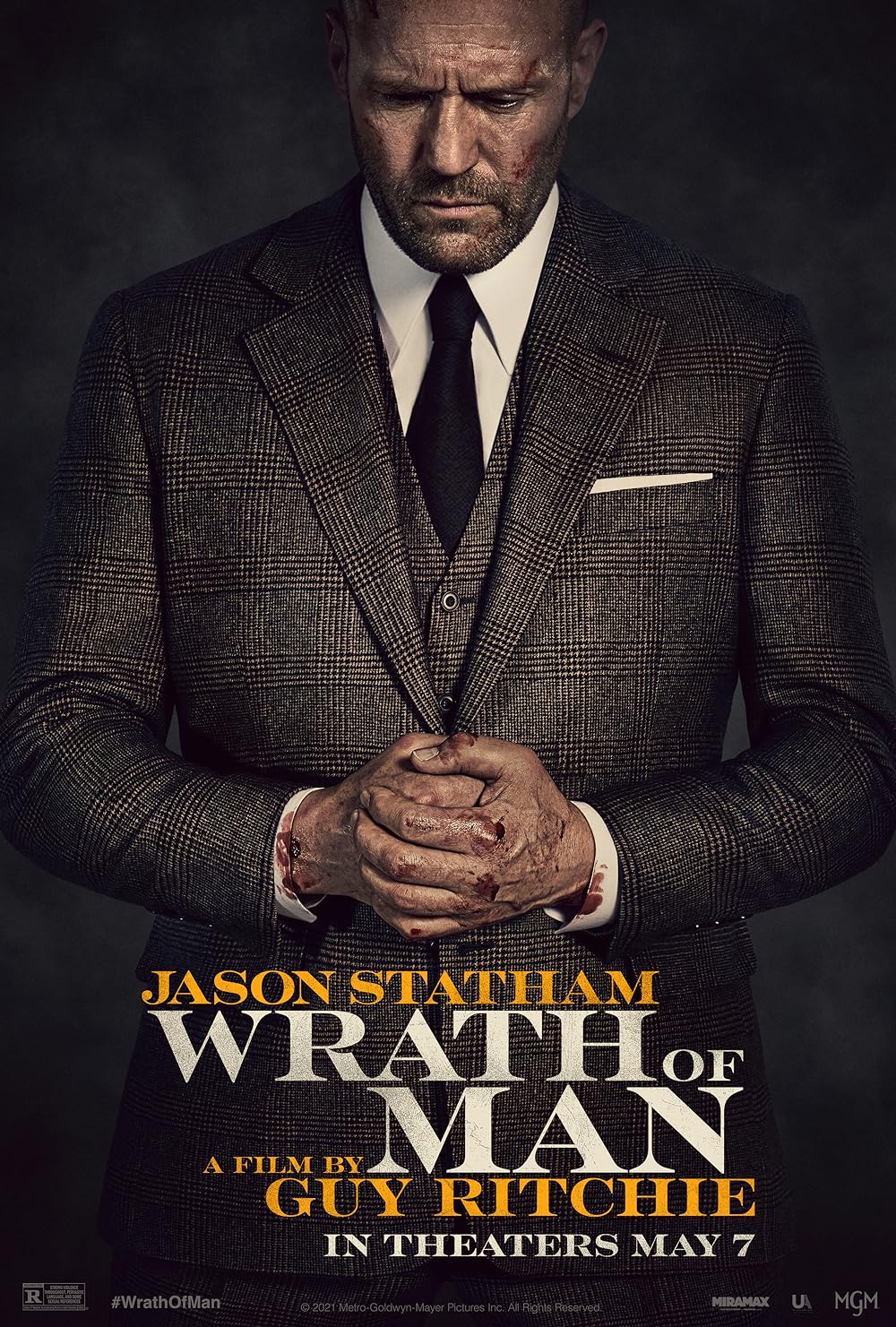

Fortunately, that seems to be changing after the newly restructured Miramax signed a deal with Ritchie for his next two pictures. The first of them, Wrath of Man, opened the summer movie season with promising box-office receipts (for pandemic times). But the most exciting thing about the film isn’t its earnings; it’s how much Ritchie has adjusted his filmmaking style into a hard-boiled crime story. A remake of the 2004 French film Le Convoyeur, Wrath of Man finds Ritchie setting aside his Tarantino-inspired hipness and embracing a classical version of British crime filmmaking—the sort found in Basil Dearden’s The League of Gentlemen (1960) and Mike Hodges’ Get Carter (1971)—combined with Michael Mann’s austere criminal professionals in Heat (1995). It also reteams Ritchie with star Jason Statham, who made his acting debut in Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels before becoming an action movie icon. For Ritchie, it’s a shift in a new direction; for Statham, it’s the actor’s most compelling performance in recent memory.

Statham plays Hill, a mysterious, single-minded character who remains mysterious well into the second act. Hill lands a job with an armored car company in the opening scenes and spends his first few weeks training under a guy nicknamed “Bullet” (Holt McCallany). Bullet gives everyone a nickname—a cowardly motormouth character played by Josh Harnett is hilariously called “Boy Sweat” Dave—and so he gives Hill the nickname “H.” While on the job, H, who remains impersonal yet clearly skilled in his work, single-handedly takes down an attempted robbery by expertly shooting several well-armed criminals. At this, his supervisor Terry (Eddie Marsan) and the company’s president (Rob Delaney) aren’t sure whether he’s a psycho or a hero, whether he should be reprimanded or promoted. Nevertheless, they resolve to keep him on, and H earns a reputation as a badass with a pitch-black sense of humor among his coworkers (after H kills several robbers, he asks “Boy Sweat” Dave, “Did you make poo-poo?” in a strangely comical moment). In the coming months, he puts a stop to other robberies. But between his general air of don’t-mess-with-me and his suspicious combat skills, H is hiding something from his fellow guards.

Soon enough, the screenplay by Ritchie, Ivan Atkinson, and Marn Davies takes us back to what motivated H’s current course of action. Wrath of Man is broken into several chapters that shift in perspective and chronology, sometimes focusing on H and sometimes on the various men who work for H. The biggest shift comes in the film’s second half when we meet a group of bored ex-soldiers, among them a steely eyed wild card (Scott Eastwood), led by Jackson (Jeffrey Donovan). How the group’s trajectory will intersect with H remains uncertain at first; so does the relevance of the film’s opening scene shot entirely from inside an armored car during a deadly robbery. And once we understand what’s driving everyone, their inevitable collision turns into a suspenseful, expertly crafted robbery and shootout sequence. Noting that the epic bank heist in Mann’s Heat is an obvious influence is beside the point; Ritchie delivers an intense, unflinching action climax full of gasps and unexpected plot turns with a clear-headed vision.

Soon enough, the screenplay by Ritchie, Ivan Atkinson, and Marn Davies takes us back to what motivated H’s current course of action. Wrath of Man is broken into several chapters that shift in perspective and chronology, sometimes focusing on H and sometimes on the various men who work for H. The biggest shift comes in the film’s second half when we meet a group of bored ex-soldiers, among them a steely eyed wild card (Scott Eastwood), led by Jackson (Jeffrey Donovan). How the group’s trajectory will intersect with H remains uncertain at first; so does the relevance of the film’s opening scene shot entirely from inside an armored car during a deadly robbery. And once we understand what’s driving everyone, their inevitable collision turns into a suspenseful, expertly crafted robbery and shootout sequence. Noting that the epic bank heist in Mann’s Heat is an obvious influence is beside the point; Ritchie delivers an intense, unflinching action climax full of gasps and unexpected plot turns with a clear-headed vision.

Despite the story’s various leaps back and forth in time, Ritchie and editor James Herbert keep the chronology clear. Their structure feels less like the narrative gamesmanship and reframing in Ritchie’s earlier crime fare—inspired by Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994)—than a novelistic approach that gives the audience information at precise times, changing our understanding of the forward-moving plot. The increasingly low-toned string score by Christopher Benstead deepens our immersion, making us feel that every detail is important and connected to the film’s progression, even when it’s not initially clear how. Ritchie also keeps us invested through a calmer visual style. He dispenses with any tricks of film speed, slow-motion fisticuffs, and exaggerated Cockney slang found in his other crime work. Comparatively, Wrath of Man looks straightforward, if expertly shot by cinematographer Alan Stewart in a series of long Steadicam sequences with an asphalt jungle color palette.

Admittedly, this review might do you a disservice by establishing expectations, which can sometimes be a moviegoer’s worst enemy. Wrath of Man is the sort of film that one should enter without knowing too much. If you anticipate nothing more than a solid Jason Statham crime yarn, you will come away surprised to discover the star elevates every moment and has rarely been better. If you anticipate something like Ritchie’s more animated films, you might appreciate his more thoughtful, restrained approach that mirrors so many merciless British crime films of yesteryear. That said, Wrath of Man’s opening credits sequence seems odd at first, echoing a kind of James Bond-styled kaleidoscope of floating heads and mythological etchings. It’s as though Ritchie wants to establish a legend. Throughout the rather grounded proceedings, these titles hardly seem fitting, until the moment that they do. By the end, Ritchie and Statham have crafted a superb crime story that methodically unfolds into a criminal underground fable worthy of Scarface or the Krays.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review