Wonder Wheel

By Brian Eggert |

Each new Woody Allen film bears a certain historical importance. He has released a new film as writer-director every year since the early 1970s. Though occasionally a year goes by without an Allen film, he sometimes releases two pictures in a year, so his output has a consistent average over the last half-century. No other filmmaker’s body of work has followed such a trajectory, and during that time, delivered an oeuvre that has more good films than bad. Some of them prove underwhelming (Hollywood Ending, Anything Else), but most of them, even what some might call an “average” Allen film (Cassandra’s Dream, Vicky Cristina Barcelona), prove more composed and better written than another filmmaker’s best efforts. Of course, there are several masterpieces (Annie Hall, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Hannah and Her Sisters, etc.) to his name, and even recent ones (Blue Jasmine, Irrational Man) worth celebrating. And so when something like Allen’s forty-eighth film Wonder Wheel arrives, it may feel like a drop in the bucket or more of the same from Allen, even while being a significant piece of film history.

For Wonder Wheel, Allen continues his partnership with Amazon Studios, which distributed his last film and produced his first foray into television (2016’s rather disastrous Crisis in Six Scenes). His latest is Amazon’s first project as both a production house and distributor, whereas their earlier releases were festival acquisitions in a distributor-only capacity. Allen once again steeps his material in nostalgia (to a fresher effect than last year’s Café Society), setting his story on Coney Island in the 1950s. A busy boardwalk milieu of rides, restaurants, and beaches appear in a light that alternates between gray-toned overcast realism and accentuated colors to heighten the drama. Adopting the classic theatrical precepts of Aristotelian tragedy, Wonder Wheel also embodies the poetic realism of Clifford Odets and the dramaturgy of Eugene O’Neill (whom the film references more than once). Given its Greek influence, his characters are self-aware and yet propelled by fate; and while being cognizant of their roles in the unfolding drama, this detail may feel distractingly on target.

Indeed, Justin Timberlake stars as peripheral narrator and fourth-wall-breaking character Mickey, a young veteran of World War II serving his postwar years as a lifeguard. Mickey also has a small apartment in Greenwich Village and studies at NYU for his Master’s in drama. He dreams of being a great playwright and admits outright that his penchant for romanticism and melodramatic characters has exaggerated his story. In other words, Mickey warns us that the resulting film will feel stagy, overemotional, and unrealistic, following in the tradition of his favorite playwrights. As a result, Wonder Wheel‘s other characters seem like familiar theatrical tropes. Ginny (Kate Winslet) once had a promising future. She was a modest stage actress in a love affair with a drummer, but her fortunes changed. She’s now fast approaching 40, serving as a waitress in a Coney Island clam bar, and trapped in a marriage to her second husband, Humpty (Jim Belushi)—a greasy merry-go-round operator with no interest in plays or films (Ginny’s favorite pastimes), just fishing and sports. Meanwhile, Ginny’s 10-year-old son, Richie (Jack Gore), fathered by her first husband, has a chronic case of pyromania that often makes for an amusing aside, until gradually it becomes disturbing.

Living in their cramped apartment near the constant pops of the Coney Island shooting gallery is slowly driving Ginny mad. The incessant sounds, the red “Wonder Wheel” light glowing into her bedroom, the profound boredom, and family pressures leave her beleaguered with migraines and seeking escape. Enter Mickey, a tonic for her stifled romanticism. Though Ginny may just be a summer fling to him, Mickey represents her chance to escape. The situation is complicated by Humpty’s daughter, Carolina (Juno Temple), who shows up after five years of estrangement, seeking refuge from gangsters (Carolina was married to a mob man but later informed on him, and now Steven Schirripa and Tony Sirico are after her). Humpty, overjoyed by her return but still wounded from being “dumped” by her, treats his daughter as though she was still daddy’s little girl, but also “like a girlfriend,” Ginny observes. And while all of Ginny’s hopes of getting away have been centered on Mickey, her dreams of escape begin to waver when it becomes apparent that Mickey has eyes for Carolina.

Living in their cramped apartment near the constant pops of the Coney Island shooting gallery is slowly driving Ginny mad. The incessant sounds, the red “Wonder Wheel” light glowing into her bedroom, the profound boredom, and family pressures leave her beleaguered with migraines and seeking escape. Enter Mickey, a tonic for her stifled romanticism. Though Ginny may just be a summer fling to him, Mickey represents her chance to escape. The situation is complicated by Humpty’s daughter, Carolina (Juno Temple), who shows up after five years of estrangement, seeking refuge from gangsters (Carolina was married to a mob man but later informed on him, and now Steven Schirripa and Tony Sirico are after her). Humpty, overjoyed by her return but still wounded from being “dumped” by her, treats his daughter as though she was still daddy’s little girl, but also “like a girlfriend,” Ginny observes. And while all of Ginny’s hopes of getting away have been centered on Mickey, her dreams of escape begin to waver when it becomes apparent that Mickey has eyes for Carolina.

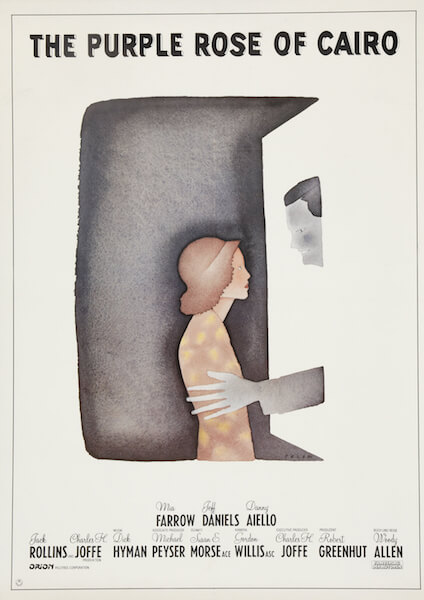

Winslet’s performance is at once devastating and visceral, a wounded character that teeter-totters on the brink of madness, just as Cate Blanchett’s character in Blue Jasmine. Her inundation is stressful and often unnerving to behold, but it’s marvelously portrayed, leading to a final scene that reaches something between Blanchett’s Jasmine and Norma Desmond. Allen, if nothing else, inspires outstanding acting. Who would expect that Jim Belushi, playing a big, sometimes abusive lug reminiscent of Danny Aiello in The Purple Rose of Cairo, would deliver such an excellent turn? Timberlake was perhaps miscast, as his modern sensibilities do not translate to the film’s setting. But then, the intentional interplay of acting styles from theatrical to natural places the viewer into a state of ever-shifting flux. At times, the characters seem a part of a realistic human drama; at others, the dramatics feel overwrought and artificial. Whenever this begins to feel unnatural or awkward, the viewer must remember Mickey’s initial warning: he has a flair for melodrama. Even so, that doesn’t make adjusting to these shifts in tone any easier or more natural.

Wonder Wheel is also one of the most stylized productions of Allen’s career. Whereas formalism has never been one of his key characteristics as a filmmaker, cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and production designer Santo Loquasto (a longtime Allen collaborator) infuse Allen’s film with expressive visuals. The light effects referenced earlier in this review function in the same manner as stage lighting designs and gels, fading in and out with the ferocious or amorous reds and oranges of sunsets or the titular Ferris Wheel to reflect the given scene. They adjust along with the characters, transitioning the viewer’s visual experience along with the drama. Likewise, Ginny and Humpty’s apartment has a deliberate stagelike appearance, whereas the gorgeous costumes by Suzy Benzinger look like theater garb. Because the film adheres to the rules of a Broadway drama, some may have an inherent difficulty watching Wonder Wheel as a work of cinema. And yet, strangely, Allen uses the limits of cinema to produce a drama that—despite borrowing stage tricks and harboring a sometimes frustrating self-awareness (“Spare me the bad drama,” Ginny says to Mickey at one point)—evokes some genuine emotions. We cannot help but yearn for Ginny to escape her prison of discontent, and the way Allen directs Winslet into a great performance with a tragic end is nothing short of impressive. Although at times uneven and filled with an obvious digital quality to achieve the setting, Allen has made another solid drama in his venerable career by embracing the emotional fire of his lead character and performer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review