Women Talking

By Brian Eggert |

(Note: This review was originally screened at the 2022 Twin Cities Film Fest and reviewed on November 7, 2022. It opens in Minnesota on January 13, 2023.)

Women Talking is a controlled and intentional piece of filmmaking by director Sarah Polley. Her production yearns for safe spaces for women to think freely, express themselves without fear of repercussions, and make their own decisions. Staged like a chamber piece yet presented in the dramaturgical format of a debate forum, the film delivers a series of declarations about the female experience that span generations. “This story begins before you were born,” says the opening narration, which seems to situate the proceedings in the distant past, albeit told from a more promising future. Similarly, Polley’s film is urgent and of the moment, yet it’s also timeless in its portrait of female agency clashing with patriarchal oppression—in this case, of the most unthinkable kind. However, Women Talking feels less interested in its specific women than the parable they inhabit. Formally and narratively, Polley has deemphasized the cultural details of the conservative Christian community on display and, in doing so, amplified the representational quality of their conflict. While the film is sure to become one of 2022’s more socially significant releases, loaded with ideas that will spark debates and lessons, the pure storytelling feels underserviced in favor of its powerful message.

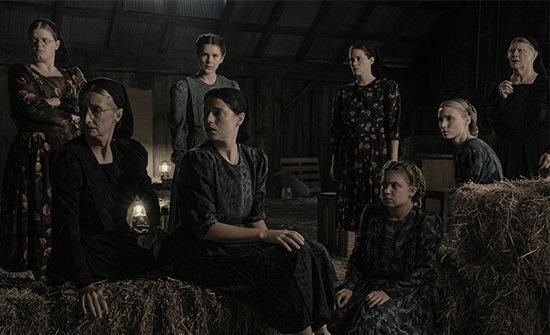

The film is based on Canadian author Miriam Towes’ 2018 best-seller about Mennonite women in Bolivia who meet secretly to discuss their situation. The men in their colony have conspired to repeatedly drug and rape the colony’s women and young girls, with some victims as young as four years old. Fortunately, the film spares the audience from any depiction of these ritualized assaults; however, it shows women waking up bloodied and bruised, and one of them has a mouthful of broken teeth, forcing her to wear ill-fitting dentures. The men claim ghosts are responsible, possibly Satan, or maybe their “wild female imagination.” In reality, the men sedate their victims with a spray typically used to anesthetize cows (a detail that remains fuzzy in the film). And those who didn’t participate remain complicit to the patriarchal power dynamic reinforced by their religion. So, while the men are away to post bail for one of their own caught in the act, the women meet in a hay loft to debate their options: Do nothing, stay and fight, or leave. After an initial vote, where each woman makes an “X” under a picture depicting their choice—the women in this community do not read and write, and they’re not allowed an education—two options tie: Stay and fight, or leave. What follows is a deliberation about the pros and cons of both options.

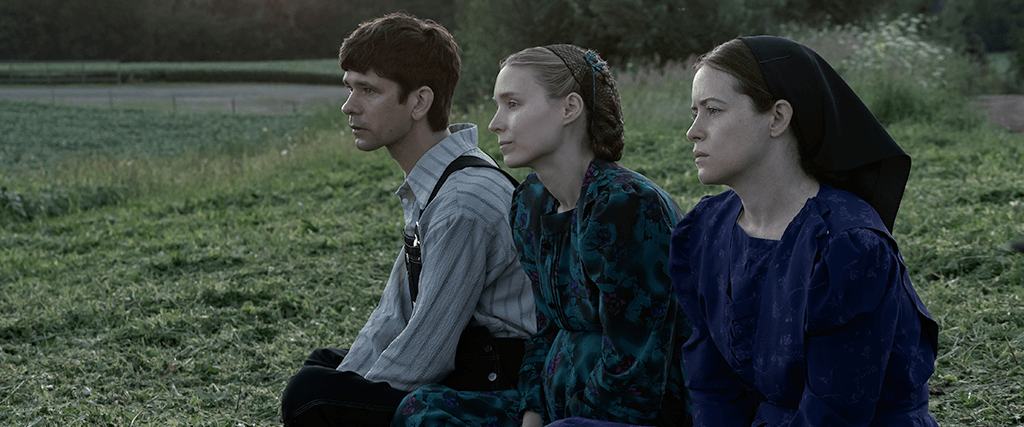

Severe as this setup may sound, Women Talking never resorts to a humorless and dry experience, even though its treatment can often be overly didactic. Even while Polley confronts grim subject matter from rape to gaslighting, her characters’ humanity emerges in moments of levity and the personalities imbued by the terrific actors. The assembled women include Rooney Mara, Jessie Buckley, Claire Foy, Judith Ivey, Liv McNeil, Sheila McCarthy, Michelle McLeod, and Kate Hallett. On the periphery, Frances McDormand (also a producer) plays a stern traditionalist who disapproves of dissent, though her face bears scars of endured abuses. The only male character, August Epp, is played by Ben Whishaw, the community’s schoolteacher whose emotional sensitivity, college education, and lack of farming skills have made him an outsider among the men. While the women debate, August records the minutes, occasionally offering his opinion, much to the annoyance of Buckley and Foy’s more heated Mariche and Salome. Mara’s voice as Ona remains one of serenity and optimism, and she often carries a benevolent smile despite being pregnant with her attacker’s child. Ivey plays the wise old owl, while McCarthy also plays an elder who amusingly insists upon telling allegorical stories about her two horses. Outside, watching over the children, there is Nettie (August Winter), who, after being raped by her brother, identifies as male and goes by Melvin.

Severe as this setup may sound, Women Talking never resorts to a humorless and dry experience, even though its treatment can often be overly didactic. Even while Polley confronts grim subject matter from rape to gaslighting, her characters’ humanity emerges in moments of levity and the personalities imbued by the terrific actors. The assembled women include Rooney Mara, Jessie Buckley, Claire Foy, Judith Ivey, Liv McNeil, Sheila McCarthy, Michelle McLeod, and Kate Hallett. On the periphery, Frances McDormand (also a producer) plays a stern traditionalist who disapproves of dissent, though her face bears scars of endured abuses. The only male character, August Epp, is played by Ben Whishaw, the community’s schoolteacher whose emotional sensitivity, college education, and lack of farming skills have made him an outsider among the men. While the women debate, August records the minutes, occasionally offering his opinion, much to the annoyance of Buckley and Foy’s more heated Mariche and Salome. Mara’s voice as Ona remains one of serenity and optimism, and she often carries a benevolent smile despite being pregnant with her attacker’s child. Ivey plays the wise old owl, while McCarthy also plays an elder who amusingly insists upon telling allegorical stories about her two horses. Outside, watching over the children, there is Nettie (August Winter), who, after being raped by her brother, identifies as male and goes by Melvin.

As the debate continues, there’s a quality that recalls 12 Angry Men (1957), wherein some women who believe they should stay and fight gradually change their minds to leave. But there’s no secondary vote or hand-raising that helps us keep track of where certain characters stand during the discussion, so a sense of progression is somewhat less apparent. Even so, Polley’s screenplay isn’t as concerned about building to a verdict as the immersive discourse. Most of the women weigh their decision against their religious convictions, yet the male-dominated religion and rules of the colony protect men and demonize women. They recognize that “We’re women without a voice” in their colony, and “It doesn’t matter what [they] think.” But as Salome admits, “I will become a murderer if I stay.” They also consider the spiritual implications: Will they be excommunicated and not allowed into the Kingdom of Heaven if they disobey their husbands or disrupt their community? Others are more interested in the here and now: “Surely there must be something worth living for in this life and not in the next.” And what about the children? If they leave, should the young boys be allowed to join them, and if so, what’s the age limit? Moreover, many worry about how they will make their way in the world if they leave.

It has been a decade since Polley last directed, and Women Talking marks her fourth time behind the camera after Away From Her (2006), Take This Waltz (2011), and her biographical documentary, Stories We Tell (2012). Her adaptation takes a pointedly symbolic approach, making the storytelling more illustrative than specific. Working with cinematographer Luc Montpellier, a fellow Canadian who shot her first two films, Polley delivers a digital image desaturated of color, like a faded photograph created by a computer. At times the picture looks almost sepia-toned, with the occasional burst of green from the farm fields or blue from the women’s dresses. The lack of color and artificiality of the digital image work to turn the film into an allegory worthy of Margaret Atwood—whose Alias Grace was adapted into a TV series by Polley and director Mary Harron—as though what unfolds could happen anywhere. By contrast, the music by Hildur Guðnadóttir is grandiose, underscoring the seriousness and importance of the subject matter. Even if many of the formal choices feel heavy-handed, Polley finds moments of beauty and hope in some Malickian magic hour shots of children playing against the sunrise, which prove less transportive when drained of color under the film’s dour visual circumstances.

Women Talking opens with a title that reads, “What follows is an act of female imagination”—a line borrowed in part from Towes’ introduction to her book. But Towes’ based her account on an actual story that broke in 2011. Even so, Polley’s imagination downplays the details of the real-life Manitoba Colony and plays up the allegorical potential, allowing the viewer to believe that the vintage farm dresses and minimal electric conveniences, such as a refrigerator, represent a time long ago—perhaps the late ’30s or ’40s. There’s little mention of Bolivia, if any that I can remember, and the characters speak in American accents, not the Low German spoken by the actual community. Polley’s careful construction of a nondescript time and place gives way to a reveal: About mid-film, an automobile arrives at the community blaring “Daydream Believer” by The Monkees, and a voice on a loudspeaker asks the members to participate in the 2010 census. Polley’s late reveal—made on the first page of Towes’ book—emphasizes how the problems detailed in Women Talking are unceasing and will continue unless women take action. Unfortunately, the writer-director’s efforts to concentrate these themes into a universal tale also lessen the story’s specificity, diminishing the degree to which these characters have equal substance as people and symbols.

Women Talking opens with a title that reads, “What follows is an act of female imagination”—a line borrowed in part from Towes’ introduction to her book. But Towes’ based her account on an actual story that broke in 2011. Even so, Polley’s imagination downplays the details of the real-life Manitoba Colony and plays up the allegorical potential, allowing the viewer to believe that the vintage farm dresses and minimal electric conveniences, such as a refrigerator, represent a time long ago—perhaps the late ’30s or ’40s. There’s little mention of Bolivia, if any that I can remember, and the characters speak in American accents, not the Low German spoken by the actual community. Polley’s careful construction of a nondescript time and place gives way to a reveal: About mid-film, an automobile arrives at the community blaring “Daydream Believer” by The Monkees, and a voice on a loudspeaker asks the members to participate in the 2010 census. Polley’s late reveal—made on the first page of Towes’ book—emphasizes how the problems detailed in Women Talking are unceasing and will continue unless women take action. Unfortunately, the writer-director’s efforts to concentrate these themes into a universal tale also lessen the story’s specificity, diminishing the degree to which these characters have equal substance as people and symbols.

As a result, the film tends to play like it’s more about ideas than characters, whereas a deeper investigation of the colony’s cultural specifics may have made the story more about human beings than making points in a sociological argument. Oddly enough, August proves the most layered and powerfully acted. His character doesn’t fit in among the women, but he’s an outcast among men and remains in love with Mara’s character. And in the end, he resolves to stay in the colony instead of striking out on his own, doomed to be constrained. In Towes’ text, the book consists of his minutes; therefore, the reader absorbs only what he observes about the women, taken from an outsider’s perspective—representing a male documenting female subjectivity. But Polley’s treatment, which captures the women’s voices without a filter, also renders them with fewer dimensions. Unlike the book, written by a woman from a man’s perspective, Polley’s camera has the potential to adopt a more direct female subjectivity. Still, most of her characters feel like mouthpieces for ideas rather than fully formed characters.

Luckily, Women Talking has ideas to spare, and it’s easy to see why the response has been so impassioned. Doubtless, it will be used as a primer for feminist theory and women’s studies courses. Through their debate, the women carefully outline the systems of power in organized religion and patriarchal hierarchies designed to keep women powerless and obedient. In doing so, the film encapsulates many of the social problems addressed by #MeToo and portrays many of the movement’s arguments about systemic abuse and subjugation. But its remarks can sometimes register more like a proclamation than the lessons of a drama. While this approach allows the proceedings to communicate a clear understanding of gender and power in cultures the world over, it also makes the film more intellectually engaging than emotionally involving at times. However, the performances remain impassioned, with Buckley and Foy being the standouts, and the experience is not without the occasional notes of cheerfulness. The final moments that look toward the future’s open road prove symbolic as well, as the women head out into the world, which they have never been allowed to see, hoping for the best. If the film can be overly allegorical at times, it’s a resoundingly hopeful and worthwhile allegory.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review