Wolfwalkers

By Brian Eggert |

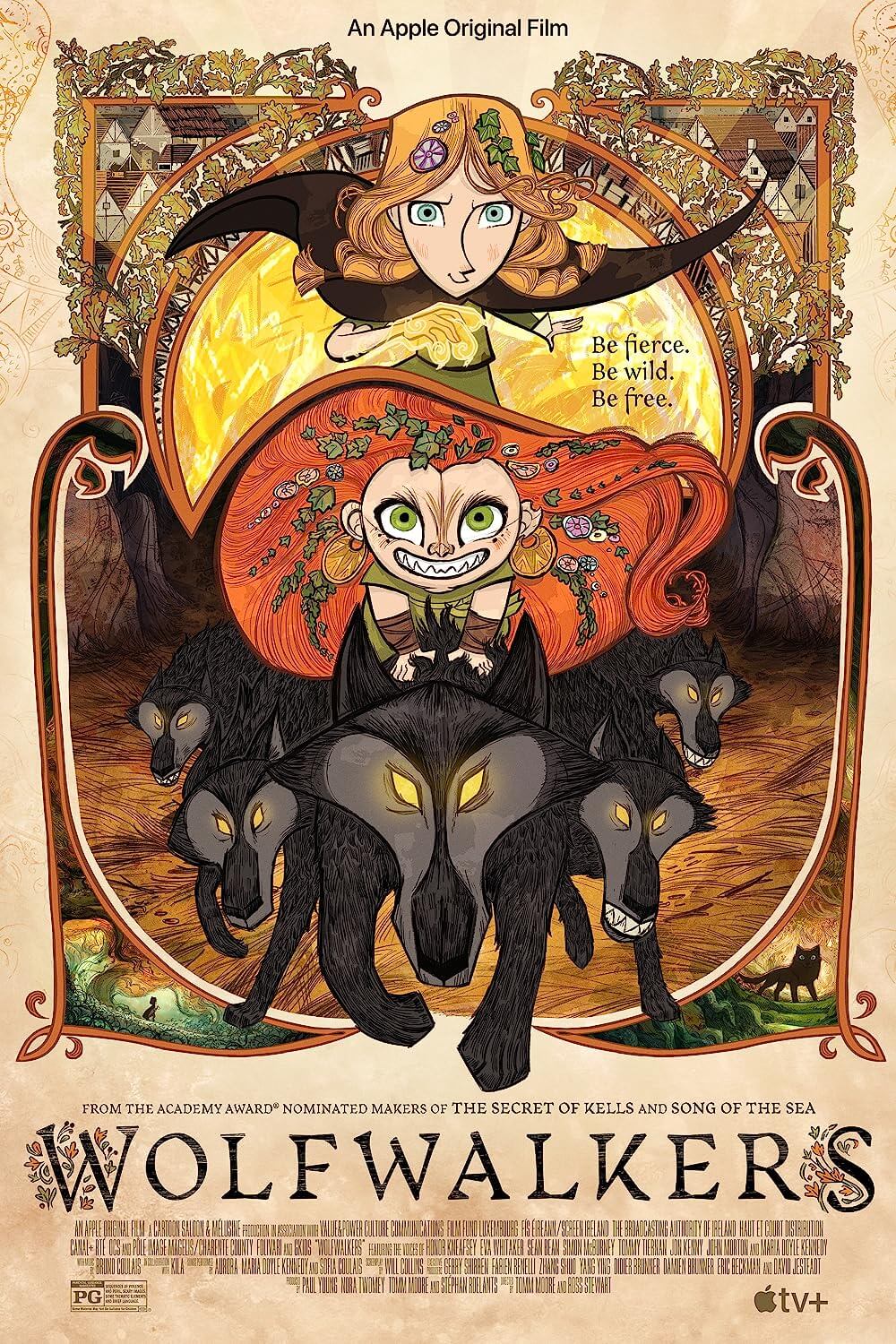

To watch the stunning Wolfwalkers, the latest from Irish animation studio Cartoon Saloon, is to feel the spirit of Hayao Miyazaki, the premier animator from Japan’s Studio Ghibli. While the story comes straight from Kilkenny, the medieval town in southeast Ireland, and the studio’s headquarters, its themes and animation style bear a resemblance to Miyazaki’s interest in ecological responsibility. It’s a film about the dangerous tide of so-called progress through fear-mongering and religious certainty that stands in contrast to Nature’s beauty and the mysticism of the wilderness. Far from mere kid’s stuff, the film is steeped in Celtic mythology and history, though it’s also ceaselessly enjoyable as an adventure story, recalling Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997). And while today’s animation usually involves computer-generated images interacting on a three-dimensional digital plane, there’s something tangible and hand-crafted about the animation in Wolfwalkers. Even though computers doubtless assisted the production, it feels like a film created by artists who remained hunched over their desks, sketching each gorgeous, transportive frame by hand. It feels like the work of artisans.

After 2009’s The Secret of Kells earned Cartoon Saloon an Oscar-nomination with a story of magic and Viking invasions, director Tomm Moore continued his exploration of Irish identity with Song of the Sea (2014), a fantasy about a lighthouse keeper and selkies. Co-directing with Ross Stewart, Moore concentrates his interest in Irish history and mythology into Wolfwalkers, easily the animation studio’s best film to date. Will Collins’ screenplay, based on a story by Moore and Stewart, transports the viewer to Kilkenny in 1650, where a walled village rests just outside of a vast, enchanted forest. Local farmers and woodcutters, trying to establish an infrastructure just outside these savage lands, have encountered a pack of wolves that threaten their progress. Enter Bill Goodfellowe (Sean Bean), a widower and hunter assigned to eliminate the wolves by order of the resident authority, the Lord Protector (Simon McBurney). Goodfellowe’s daughter, Robyn (Honor Kneafsey), accompanied by her trusty falcon named Merlin, hopes to become a hunter as well. However, Goodfellowe plans to keep his promise to his late wife to protect their daughter, even if it means constraining Robyn to domestic drudgery.

Of course, Robyn disobeys her father and finds herself entangled with a feral, red-haired forest girl named Mebh (Eva Whittaker), a Wolfwalker who can control her pack of wolves with a howl. Mythical creatures that thread the division between humanity and Nature, Wolfwalkers appear human by day and, while asleep at night, their animal spirit emerges and materializes into a wolf. When Mebh accidentally bites Robyn, our hero becomes a Wolfwalker as well, and in the process, learns that there’s more to the wolves than she believed. Not only does she uncover the beautiful, autumnal world in the forbidden forest—a space of lush greens and burnt oranges that radiate from the screen—she is exposed to a unique visual experience whereby scents become illuminated in glowing, trailing auras in an otherwise dark world (recalling the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Disney’s 1941 Dumbo). Now forced to see the world from a wolf’s perspective, she recognizes that the Lord Commander’s plan to kill the wolves and conquer the forest will have dire consequences for Mebh and her kind, a group to which Robyn now belongs.

Of course, Robyn disobeys her father and finds herself entangled with a feral, red-haired forest girl named Mebh (Eva Whittaker), a Wolfwalker who can control her pack of wolves with a howl. Mythical creatures that thread the division between humanity and Nature, Wolfwalkers appear human by day and, while asleep at night, their animal spirit emerges and materializes into a wolf. When Mebh accidentally bites Robyn, our hero becomes a Wolfwalker as well, and in the process, learns that there’s more to the wolves than she believed. Not only does she uncover the beautiful, autumnal world in the forbidden forest—a space of lush greens and burnt oranges that radiate from the screen—she is exposed to a unique visual experience whereby scents become illuminated in glowing, trailing auras in an otherwise dark world (recalling the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence in Disney’s 1941 Dumbo). Now forced to see the world from a wolf’s perspective, she recognizes that the Lord Commander’s plan to kill the wolves and conquer the forest will have dire consequences for Mebh and her kind, a group to which Robyn now belongs.

The gorgeous, inspired animation feels far more complex and multifaceted than the studio’s earlier projects, which look like rough drafts next to this polished, fully realized film. There’s a shifting style that at points looks like a storybook come to life, evidenced in forest scenes where the expansive landscape appears to be composed of watercolors and sketchy inks, the lines of which have a fascinating, unpolished flick-of-the-wrist quality. Elsewhere, usually in establishing shots or master shots, the film employs the flattened perspective of Chinese landscape painters or Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s peasant scenes. The character designs prove just as diverse, shifting from the fluidity of the wolf pack that moves in unison like a cloud of smoke to the boxy contrast seen in lumberjack characters. The influence of Japanese animation ranges from extra-large catchlights in Robyn and Mebh’s oversized eyes to the directors’ use of split-screens and whooshing backgrounds. Wolfwalkers borrows much but never feels stylistically derivative; its influences come together into something that’s unlike anything you’ve ever seen.

To that end, here’s a film that also asks questions about conformity and difference. At one point, Goodfellowe tells his daughter, “We must do what we’re told.” She asks him why, and his response taps into a condition that has driven the human race for centuries: “I’m afraid.” It’s not the reassuring, believe-in-yourself message that usually resides at the center of animated fantasies by Dreamworks or Disney. But it leads to Robyn understanding her father’s motivations, and those of other human beings, and it ultimately drives her decision to choose her fellow Wolfwalkers and the wonders of the forest over Kilkenny and its narrow-minded inhabitants—many of them portrayed as grotesques from odd angles. The Lord Protector uses fear to maintain control over his subjects, whether by the threat of punishment or unknown mysteries hidden in the forest—the “pagan nonsense” that uses dangerous, unholy magic. But fear, to quote a favorite science-fiction text, is the “mind-killer.” By understanding that her father will not do the right thing out of fear, Robyn recognizes how the Lord Protector manipulates Kilkenny.

Wolfwalkers also contains a thrust of feminism. Robyn wants only to become a hunter like her father, a role beyond what this patriarchal Christian society will allow. Goodfellowe tells his daughter, “Help me by doing your work and staying in town.” At the grim scullery, accented with a stony-gray palette, and where “work is prayer,” Robyn sees women who have chopped fish, churned butter, and laundered sheets all their lives. There are few other alternatives; the Lord Protector punishes women who do not work. But if her place is mopping floors, it’s a station no different than the cage where the Lord Protector keeps Mebh’s mother, Moll (Maria Doyle Kennedy). Whether she sets out into the wilderness to hunt or embraces her new form as a Wolfwalker, Robyn’s transformation cannot help but recall Merida from Pixar’s underrated Brave (2012), given its use of Gaelic culture and feminist self-actualization. The commentary gives way to a queer reading as well, most apparently in the scenes between Robyn and Mebh that ring with sincerity and affection, and how Robyn shatters perceived social and societal norms by running toward her new family.

Wolfwalkers also contains a thrust of feminism. Robyn wants only to become a hunter like her father, a role beyond what this patriarchal Christian society will allow. Goodfellowe tells his daughter, “Help me by doing your work and staying in town.” At the grim scullery, accented with a stony-gray palette, and where “work is prayer,” Robyn sees women who have chopped fish, churned butter, and laundered sheets all their lives. There are few other alternatives; the Lord Protector punishes women who do not work. But if her place is mopping floors, it’s a station no different than the cage where the Lord Protector keeps Mebh’s mother, Moll (Maria Doyle Kennedy). Whether she sets out into the wilderness to hunt or embraces her new form as a Wolfwalker, Robyn’s transformation cannot help but recall Merida from Pixar’s underrated Brave (2012), given its use of Gaelic culture and feminist self-actualization. The commentary gives way to a queer reading as well, most apparently in the scenes between Robyn and Mebh that ring with sincerity and affection, and how Robyn shatters perceived social and societal norms by running toward her new family.

In addition to its feminist message about the importance of independent thought, the film taps into a postcolonial commentary on the presence of Protestant settlers from Great Britain in Ireland. Colonizers sought to wipe out many of the local myths and replace them with Christian ideals. The Lord Protector, too, represents an English authority who seeks to “tame” the Irish wilderness, creating an association between pre-Christian Ireland and the untamed and dangerous. By the time this story takes place, the British Empire had already suppressed the Gaelic language and culture to a whimper throughout the North, leading to an eventual drive to revive and remember that inspired many during the later Irish Revolution. These historical underpinnings deepen Wolfwalkers into a layered, stirring post-colonial fable fuelled by centuries of Irish animosity toward their English colonizers.

Wolfwalkers is loaded with multi-textual potential, allowing viewers to cling to any number of readable, often germane, commentaries embedded into the story. But the film’s themes work so well because the characters and animation have so fully immersed us in the experience. The animation goes beyond being pleasing to the eye; it emboldens the film’s various undercurrents, using color, along with the harshness of lines and angles, to establish the conflict between seemingly civilized men who make false claims against the freeing, bright, welcoming mysteries of Nature, extending into the supernatural and spiritual. Few filmmakers in animation have linked humanity and Nature to the artform so fully; only the aforementioned Miyazaki, who sought a balance between progress and the natural world, compares. Disney’s overproduced products and Pixar’s digital sheen make their products feel like polished, blunt objects next to the rustic, homespun appeal of Cartoon Saloon’s masterpiece. At once empowering and enchanting, Wolfwalkers is a sophisticated, rousing, and earthy adventure that plays to both hearts and minds.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review