Wish

By Brian Eggert |

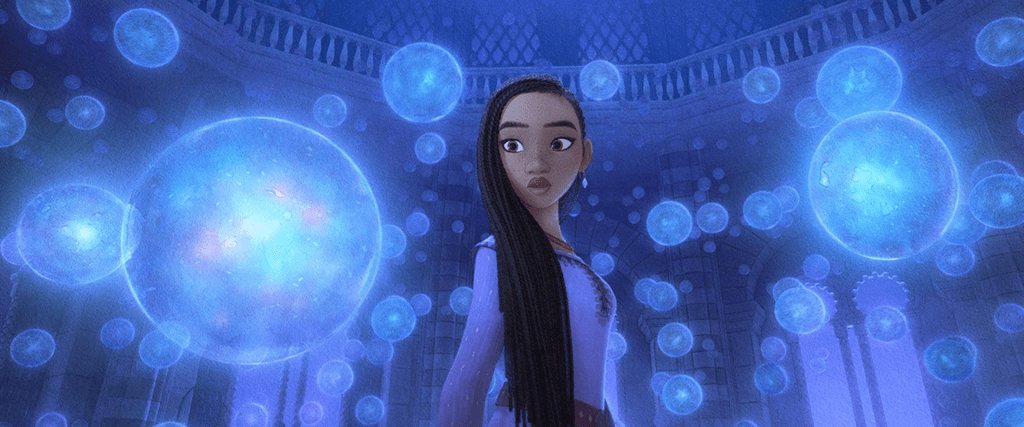

Disney’s Wish tells the story of a Mediterranean island community called Rosas, which is idyllic, inclusive, and run by a sorcerer-king named Magnifico, voiced by Chris Pine. Magnifico collects his people’s most cherished wishes on their eighteenth birthday and holds onto them in glass orbs, while the newly made adults forget “without regret” what they wished for. Although he grants one citizen their wish once a month, the story reveals that Magnifico is a despot, and his small graces are only to keep his people ingratiated and dependent, boosting his ego. The storybook conflict entails a defiant teen heroine, Asha (Ariana DeBose), who, after learning Magnifico is less generous than he presents himself, enlists a few of her friends to lead a rebellion and allow people to wish freely for something better—and to realize that they have the power within themselves to fulfill their dreams. In purely thematic terms, Wish will spark with moviegoers who feel disenfranchised by those in power. Unfortunately, the filmmakers’ methods of telling this story are commercially crass and visually uninspired, turning what might have been a worthwhile narrative into a product about Disney playing with itself.

Let’s start with the good. I appreciated how Magnifico’s instantly suspicious modus operandi leads to the story’s healthy cynicism about egocentric leaders—that the guy in whom you put your faith is using you to further his power and exploit you. Pine plays this against type, like an evil version of his charming character from this year’s Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves. After Magnifico complains that he doesn’t get unquestioning allegiance in the song “This Is the Thanks I Get?!,” he learns to feel better about himself by literally crushing people’s dreams. The movie encourages skepticism in a world of cultish devotion to certain political leaders. Elsewhere, Asha’s rebellion against Magnifico validates the importance of everyone’s dreams, instilling a theme of unity because everyone hails from the same stardust, so we should try to see each other by our common traits. Her eventual call for action is punctuated with the genuinely rousing rally song, “Knowing What I Know Now,” written by current-era Disney staple Dave Metzger, with help from Julia Michaels and Benjamin Rice. Many of the other songs fall flat, but I found these two thoughtfully linked with the story’s themes.

Apart from the impassioned ideas and a couple of memorable songs, Wish tests the viewer’s patience with a visually misguided animation style. Directed by Frozen (2013) helmer Chris Buck and that film’s storyboard artist Fawn Veerasunthorn, Wish features characters who could pass in the kingdom of Arendelle. They have generic, plastic shapes, no doubt designed with their eventual toys in mind. More discomfiting, the movie’s characters inhabit a CGI world artificially designed to look hand-drawn, complete with watercolor skies and bold outlines around every edge, including their facial features and bodies—as though animated by Telltale Games. Within the bold outlines, the animation looks like a computer’s approximation of hand-painted artistry. Perhaps this blend of hand and computer-generated animation is an intentional amalgam of the company’s history of styles—from individually painted cells to whole worlds designed in a digital environment. But the look never comes together into a singular conception; instead, the characters feel removed from their backgrounds, and the styles present an off-putting contrast. My eyes were constantly at odds with the execution.

Then it gets worse. At a certain point, Asha wishes upon a star, like in the song from Pinocchio (1940), whose lyrics promise, “When you wish upon a star, Makes no difference who you are, Anything your heart desires, Will come to you.” This marks the arrival of a magic star character, predictably named Star, who looks like a yellow version of Kirby from the 1990s Nintendo game. Star arrives and gives Asha’s pet goat, Valentino (Alan Tudyk), his desired ability to talk, and then grants countless other wishes using stardust. But it also transforms Wish into a product designed to celebrate the House of Mouse’s centennial, with a fawning series of references to their various intellectual properties. Disney devotees may gobble this up, but it’s difficult not to feel nauseated by the self-aggrandizing commercialism evidenced in singing trees, bluebirds on Asha’s shoulder, a deer named Bambi, thumping rabbits, a grizzly named John, a nod to Neverland, a wink at Mary Poppins, a Tarzan jungle cry, an evil “mirror mirror” taunt, and Asha’s seven friends with familiar characteristics (grumpy, sneezy, dopey, et al.). Wish barely pretends to disguise its allusions, leading to the end credits that display images from Disney’s most iconic movies. These references don’t serve the narrative; they serve the extra-textual brand.

Then it gets worse. At a certain point, Asha wishes upon a star, like in the song from Pinocchio (1940), whose lyrics promise, “When you wish upon a star, Makes no difference who you are, Anything your heart desires, Will come to you.” This marks the arrival of a magic star character, predictably named Star, who looks like a yellow version of Kirby from the 1990s Nintendo game. Star arrives and gives Asha’s pet goat, Valentino (Alan Tudyk), his desired ability to talk, and then grants countless other wishes using stardust. But it also transforms Wish into a product designed to celebrate the House of Mouse’s centennial, with a fawning series of references to their various intellectual properties. Disney devotees may gobble this up, but it’s difficult not to feel nauseated by the self-aggrandizing commercialism evidenced in singing trees, bluebirds on Asha’s shoulder, a deer named Bambi, thumping rabbits, a grizzly named John, a nod to Neverland, a wink at Mary Poppins, a Tarzan jungle cry, an evil “mirror mirror” taunt, and Asha’s seven friends with familiar characteristics (grumpy, sneezy, dopey, et al.). Wish barely pretends to disguise its allusions, leading to the end credits that display images from Disney’s most iconic movies. These references don’t serve the narrative; they serve the extra-textual brand.

Indeed, watching Wish, you begin to question whether Disney is in the business of creating magic or perpetuating its brand. In this case, it’s the latter. Of course, movies are art and commerce, and that dynamic has always been tricky. A good one will deliver a laudable aesthetic experience while earning its investors a profit. Then again, a movie can be great art, whether commercially successful or not. But when a movie forsakes its artistry in the name of selling itself and the corporation, it may not cease to be art, given all the creative work that went into it, but it’s bad art. Wish suffers from this imbalance. The scales have tipped to the side of blatant commercialism so that, along with its ungainly animation style, the conspicuous branding distracts from the storyline. It turns the movie into a Disney billboard, and I couldn’t enjoy the story because the filmmakers kept reminding me of the company’s legacy of trademarked characters. Some people complain about the commercials before the feature presentation; here, the feature presentation is a commercial.

Filmmakers and even corporations can celebrate a brand within a movie well, even creatively. Consider what the James Bond franchise did for its fiftieth anniversary, which coincided with the release of Skyfall (2012). That film was designed as a compendium of brand tropes amassed over five decades, and deployed into a singular experience—enriched by inspired visuals, formal ambition, and expert storytelling. But it wasn’t a reference machine; you aren’t constantly reminded of Bond characters from other movies or asked to “remember when.” By contrast, Wish feels engineered by a promotional department. Whereas recent Disney titles from Zootopia (2015) to last year’s Strange World have a life of their own, with thoughtfully conceived worlds that immerse the viewer, Wish rarely captivated me. What a shame, given that its message—to own your dreams and not entrust them to anyone else, and instead make them happen through commitment and hard work—is so inspiring. Walt Disney made his dreams a reality a century ago. But things have changed, and the intrepid spirit of one artist has gradually mutated into a multinational conglomerate bent on selling its merchandise. I only wish it wasn’t reminding us of Disney’s inventory while crafting its latest product.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review