Wind River

By Brian Eggert |

After writing two highly acclaimed screenplays—Sicario (2015) and Hell or High Water (2016)—Taylor Sheridan makes his directorial debut on Wind River, an original scenario based on actual events that occurred in 2012. Much like his earlier efforts, the film places wounded characters in tense, violent situations that investigate larger issues in America’s cultural and sociopolitical realms. On the surface, however, the story plays out in the manner of a superb whodunit, albeit with an emotional resonance that builds gradually. The film’s social issue of choice concerns the unchecked degree of crime, especially missing women, on the Native American reservation of Wind River, Wyoming; though, this may not be apparent until the final frames. Rather, the more centralized concern involves the general state of the Reservation and how, despite being situated in the United States, it receives little outside support. Set amid snowy mountains and punishingly low temperatures, Wind River’s inhabitants endure high unemployment rates, a rampant drug problem, and lingering dejection and gloom. “Luck don’t live out here,” says one character. “Luck lives in the city.”

With a moody score performed and sung by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis, Wind River has the tonal sparsity of a Cormac McCarthy novel, the moral justice of a revisionist Western, and hits many beats that a detective procedural might. At the same time, the film’s almost noirish atmosphere contrasts the overcast skies and blindingly white panorama of the Rocky Mountains. Only Nicholas Ray’s On Dangerous Ground (1951) and Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan (1998) have blended a wintry backdrop with a pulpy crime scenario so well. In each of his screenplays to date, Sheridan’s tough-skinned characters deliver crackling dialogue under pitch black conditions; the same goes here, but the situations become horrifically grim—I writhed in my seat during one scene, unable to escape the agony and inevitability of what was happening onscreen. Nevertheless, Sheridan has a way of allowing his narrative to unfold not as a series of plot points we see coming, but as part of a lean, skillfully handled thriller.

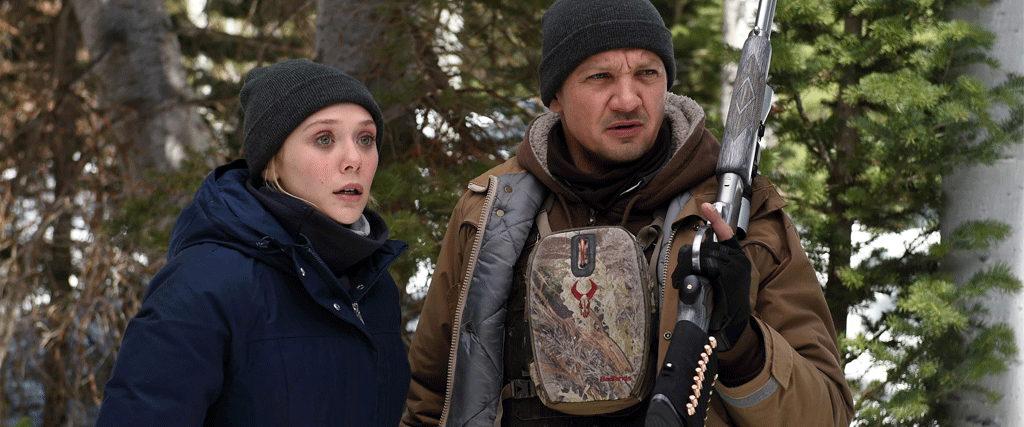

Jeremy Renner stars as U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent Cory Lambert, an experienced tracker and hunter of wild predators such as coyotes and wolves on the Wind River Indian Reservation. Tasked with hunting a family of mountain lions, Lambert comes across the frozen corpse of Natalie (Kelsey Asbille), a young Native American woman that was friends with his late daughter. To investigate, the FBI sends an in-over-her-head agent, Jane Banner (Elizabeth Olsen), but she’s unprepared for the frigid weather and unaccustomed to Reservation culture. She enlists Lambert to guide her through the terrain, alongside tribal policeman Ben (Graham Greene). After an autopsy, it’s discovered that the victim was raped, ran several miles in the snow to escape, but then died from exposure. That last part is tricky, as the coroner refuses to list Natalie’s death as murder, given that the cold killed her; meaning, the FBI doesn’t consider the matter a priority. “This isn’t the land of waiting for back up,” Ben tells her. “This is the land of you’re on your own.”

With no outside help, Banner and Lambert interview the victim’s parents and various suspects. The former demonstrates her lack of sensitivity when dealing with Natalie’s father (Gil Birmingham, excellent), while the latter cannot help feel motivated by the stinging pain of his own daughter’s recent death. Although Olsen provides a functional, if endearingly naive character, similar to Emily Blunt’s role in Sicario, Renner’s three-dimensional portrayal may be his best to date. A divorced and taciturn winter cowboy, Lambert knows the landscape, how to track men in the snow, and how to compartmentalize his mourning. He’s a damaged hero who remains in control of every situation, but his wounds will never heal and he accepts that. Most effective are Asbille and Jon Bernthal in the film’s only flashback, a nauseating few minutes of screentime that recall the tense energy of the roadside scenes in last year’s Nocturnal Animals, and with a similar outcome.

With no outside help, Banner and Lambert interview the victim’s parents and various suspects. The former demonstrates her lack of sensitivity when dealing with Natalie’s father (Gil Birmingham, excellent), while the latter cannot help feel motivated by the stinging pain of his own daughter’s recent death. Although Olsen provides a functional, if endearingly naive character, similar to Emily Blunt’s role in Sicario, Renner’s three-dimensional portrayal may be his best to date. A divorced and taciturn winter cowboy, Lambert knows the landscape, how to track men in the snow, and how to compartmentalize his mourning. He’s a damaged hero who remains in control of every situation, but his wounds will never heal and he accepts that. Most effective are Asbille and Jon Bernthal in the film’s only flashback, a nauseating few minutes of screentime that recall the tense energy of the roadside scenes in last year’s Nocturnal Animals, and with a similar outcome.

Most of the film operates at a slow-burning pace, gradually revealing the layers underneath Lambert and, by osmosis, the complicated and broken world of the Reservation. In one sequence, the investigators knock on the door of a squalid drug den whose ragged inhabitants respond in a sudden burst of unexpected violence. Indeed, Wind River focuses more on its characters than violence, but when a shootout occurs later in the film, it’s handled as absolute chaos, an effective and jumbled assault that never feels as though Sheridan has lost control. The sequence builds with gradual paranoia before exploding onto the screen, and then ends before turning into a disposable action scene. Director of photography Ben Richardson never romanticizes the setting either, even in the film’s few sweeping mountain shots. Early on, the snow and trees are associated with death and a punishing way of life. That feeling of isolation from the surrounding danger never subsides. Late in the film, Lambert explains that only hard-won survivors live in this region. There’s no time to stop and enjoy the view.

As a writer, Sheridan takes his time to establish a distinct environment and its sometimes impenetrable characters, telling the story that has no intention of rushing the viewer to the climax. Wind River has been directed with the same degree of patience and substance that permeates his writing. The texture and earthiness of the storytelling lend the picture a unique identity, despite the scenario’s reliance on several familiar tropes of the Hollywood thriller. Comparisons could be made to many other murder mysteries, but Sheridan uses those tropes in such a way that imbues his film with a resounding sense of innovation, just as his earlier works have done. His craftsmanship and rather cynical perspective behind the camera immerse the viewer in his violent, affecting world. Even though not as many will see Wind River compared to Sheridan’s earlier credits as a writer-only, it’s a confident debut that doesn’t feel like a debut at all, but the realization of a writer’s on paper to film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review