Wildlife

By Brian Eggert |

There comes a point in every child’s life when they recognize the humanness of their parents and cease to perceive them as heroic and infallible. Just as a young person emerges from adolescence and begins to understand that there’s a world beyond their home, parents become smaller somehow. Soon enough, it’s evident that your parents are just as confused and frightened, just as uncertain about how to operate in the world as you are. They’re faking it—and you, being a child, have bought into the myth. Wildlife is about this realization. Based on Richard Ford’s 1990 novel, the film explores material well-treaded by the cinema. It’s a coming-of-age story that takes place in the 1960s, an era defined by the obliteration of the American Dream—the suburban nuclear family, two cars in every garage, and an almost sickening wholesomeness. Ford’s symbol of choice to reflect a doomed culture—from the atomic and Red scares to the perceived abandonment of so-called American values by the counter-culture movement—is a raging forest fire on the border between Canada and the story’s setting in Great Falls, Montana. It’s as though the fire has burned up everything good and pure, the virtue of youth’s obliviousness.

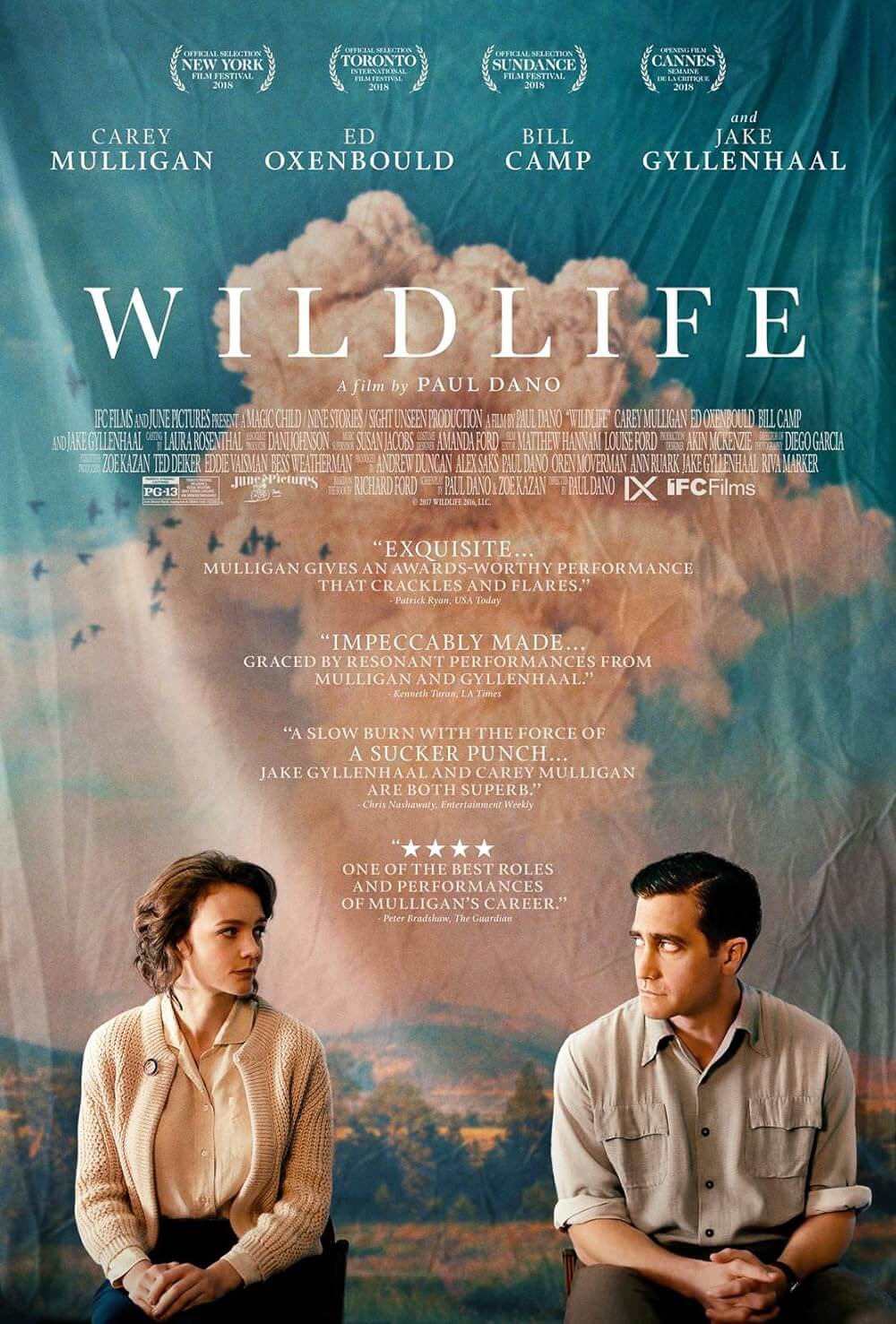

Ford’s literary conceit has been fully embraced by Paul Dano, the actor who makes his directorial debut on Wildlife and, refreshingly—unlike other actor-directors Clint Eastwood, Kevin Costner, or more recently Bradley Cooper—has decided to remain behind the camera. Collaborating on the adaptation with his partner Zoe Kazan, Dano exhibits a masterful application of craft and aesthetic clarity for a debut film, or any film. Although the period details recreated by production designer Akin McKenzie capture the 1960s setting, there’s an intentional void at the center, a deafening muteness that seizes the perspective the 14-year-old protagonist, Joe (Ed Oxenbould, from The Visit). His parents, Jerry and Jeanette, exceptionally performed by Jake Gyllenhaal and Carey Mulligan, have just settled in Montana, the latest in a series of moves. Joe, though tired of relocating, sees his parents as estimable, unfailing, and even admires the way they flirt. But then Jerry, a talented golf instructor, finds himself fired, losing the family’s sole income. Despite being asked back to work the next day, Jerry’s restlessness and pride expose a fissure of instability in the family. Joe watches as, over the course of the film, everything he knows about his parents is warped and perverted.

Joe quickly becomes an intermediary between two people who have stopped trying to understand each other. He’s the recipient of orders like “Tell your mother…” or “Tell your father…”—in the way many children become the go-between to parents who make their failing marriage their child’s issue. Joe begins to see his father, now sleeping on the couch and drowning his sorrows in beer, as someone who needs to be asked, “Are you ok?” His otherwise stable mother unhinges from her routine. Jeanette starts teaching swimming classes at the YMCA, while Jerry writhes in self-pity and despair for reasons that remain unclear, at least to Joe. Soon enough, Jerry takes a dangerous job fighting fires in the mountains, promising he’ll return with the first snowfall. With this, Jeanette shuts down. She aims her loneliness in the direction of Mr. Miller (Bill Camp), a well-fixed local, and also stops caring for Joe as a parent and speaks to him in an all-too-frank way. She acts out in a series of desperate, lonely, jumbled behaviors, all of which Joe witnesses with equal measures of fear and confusion over what’s become of his family. Even as he watches his family collapse, one cannot help but remember earlier scenes, before the breakdown, where both Jerry and Jeanette seemed to be acting their way through their marriage. Their behavior is something Joe has just become old enough to notice, distracting him from school and the female classmate (Zoe Margaret Colletti) that he’s too preoccupied to fully befriend.

Transitioning a first-person singular novel into a film often misses the mark, as recreating the subjectivity of the main character in an inherently third-person medium results in creative casualties. Rather than attempting a dully faithful adaptation, Dano resolves to spend most of the runtime with Joe, watching him observe his parents, while also introducing brief detours that explore the parents’ lives. Joe does not witness Jeannette applying for a job or Jerry walking outside for a smoke, for example. And there are many brief but important moments that linger on Jeanette’s face after Joe leaves the room, giving the audience a moment with her. To be sure, there’s an almost suspicious assuredness behind Dano’s approach, in that hardly a moment feels wasted. It’s also a mannerist production in how formally austere it is. Filmed by Diego García, who shot the dreamlike Cemetery of Splendor (2015) for Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Wildlife uses desaturated colors and plain, portrait-like framing throughout. Notice how the top of the frame often cuts off just above the character’s eyebrows, affecting an intimacy in the given scene that also suggests there’s more off-screen—more beyond what Joe can perceive about the situation. The framing is informed by the closing scene, where Joe, who works as an assistant to a local photographer, insists they take a final family portrait together.

During his press tour, Dano admitted that Ford’s novel appealed to him because, like Joe, he experienced his formative teenage years under the duress of quarreling, eventually divorcing parents. Watching Wildlife, it occurred to me that a potentially large segment of the film’s audience would not be as affected by the material as Dano, or myself. Much like Joe, I spent the later years of my teenage life trapped between parents who were on different wavelengths and, over time, recognized that these two people were not only unhappy together but were using my presence as a crutch. As their own discord meant they disappeared into their own individual spaces, I did too. Meantime, I noticed every microaggression, felt stifled by the lack of communication, and finally realized that my parents’ marriage would not last. Whereas Joe’s experience can be perceived through Ford’s prose, Dano’s film captures these same emotions by a camera that lingers on Oxenbould’s sensitive face. An empathetic viewer can assume what Joe feels about his parents as he watches their marriage crumble before him, but those with a first-hand understanding may experience Wildlife on a higher level. I suppose this is true of any work of art that has a particularly relatable subject matter for a specific viewer.

This is all a way of saying, with perhaps too much openness for a film review, that my experience with Wildlife was intensely emotional. It struck me in a personal way I was not prepared for, and therefore, my reaction is not entirely forged in a critical perspective alone. Some will not grasp, or be able to project, the weight of these situations and their effect on Joe, beyond what’s communicated by the filmmaking. Dano’s style could be described as cold or removed, though the film’s atmosphere comes from the experience of Joe’s uncertainty, and the director’s compassion for his protagonist. Dano’s control throughout Wildlife does not apply to his actors, who perform in scenes of such complexity and unconstrained emotion that it would be impossible to reduce their characters to mere tropes. At one point in the film, Jeanette asks Joe what happens to animals in a forest fire. They either adapt or burn up, his mother tells him. However obvious and potent a metaphor this becomes for Joe’s place within the crumbling family, it’s evocative imagery that Dano renders in elegant, studied visuals, and earns its dramatic weight from the three fully inhabited performances at the film’s center.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review