Wild at Heart

By Brian Eggert |

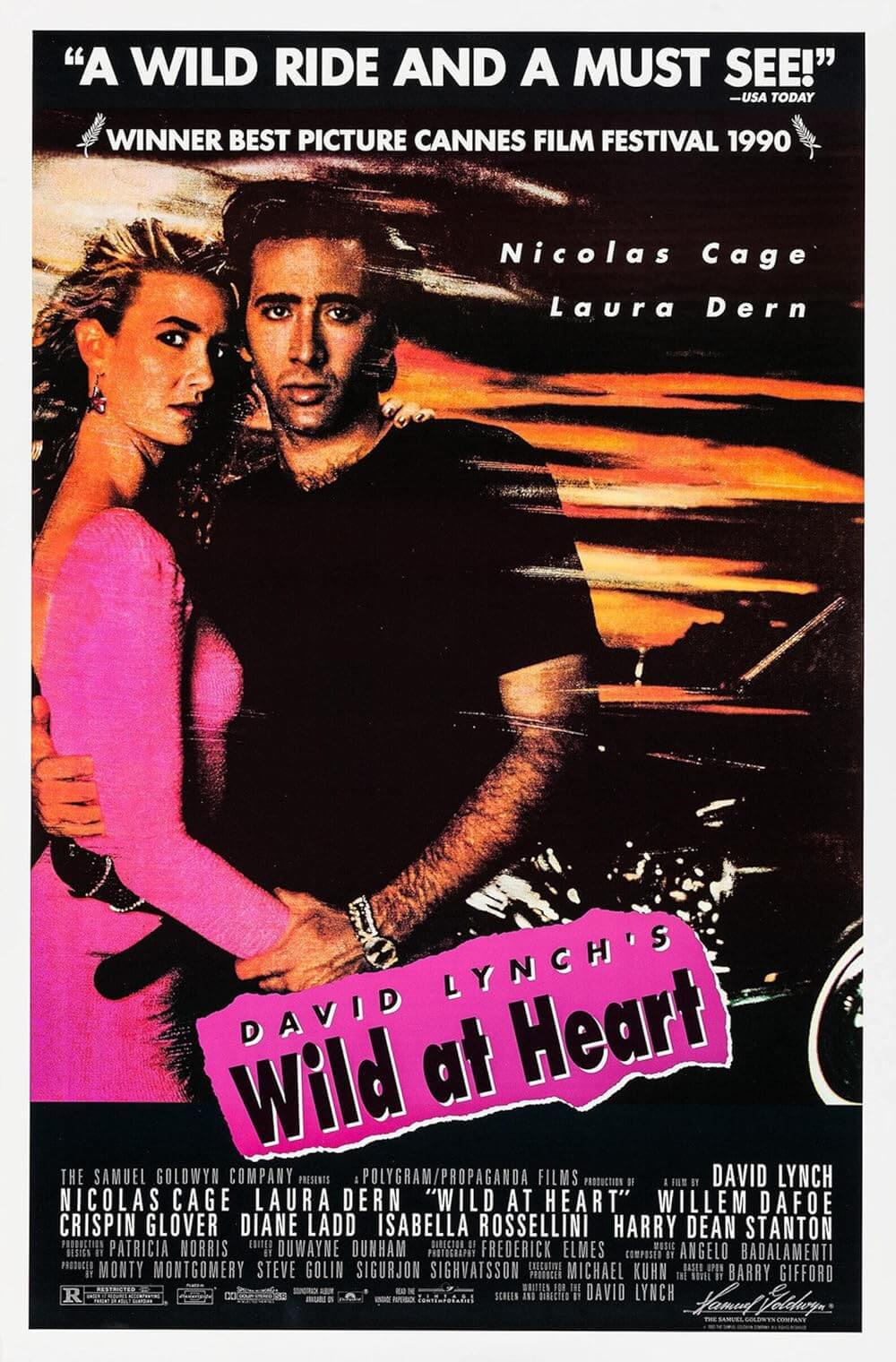

David Lynch achieves combustible, grotesque poetry in Wild at Heart, the director’s highly divisive film from 1990. This Bonnie and Clyde-esque road movie and love story features Nicolas Cage as a criminal Elvis wannabe and Laura Dern as his sexpot goddess. On the run from authorities and anyone else who would stop them, the rebellious pair drives through Lynch’s fantasyland of incendiary violence, rabid sex, and references to The Wizard of Oz—the lot of it described best by Dern’s character: “This whole world is wild at heart and weird on top.” A strange blend of goofy humor and frighteningly dark situations, Wild at Heart reeks with the smell of cigarettes, sexual abandon, bloody violence, bad teeth, and vomit. Based on Barry Gifford’s 1989 novel of the same name, Lynch freely adapted the film into something else entirely, a fusion of extreme light and dark put through the director’s surreal perspective. And yet, it remains one of Lynch’s most undervalued and misunderstood pictures.

Before Lynch began work on Wild at Heart, he entered perhaps the highest, most commercially successful period in his career, where he was lauded as a proverbial Renaissance Man. Blue Velvet (1986) had opened to mixed reviews but instant cult status. Twin Peaks, the director’s oddball television mystery, earned massive ratings in the United States. He also held several exhibitions of his fine art and even staged a musical performance with Angelo Badalamenti called Industrial Symphony No. 1. When Wild at Heart screened at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, he was more popish than he would ever be again. The director even held a Twin Peaks party at Cannes where pie and coffee were served, and attendees enthusiastically celebrated their love for Lynch’s safe-for-prime-time program. It could be argued that much of popular America had not seen Blue Velvet, nor The Elephant Man (1980), and certainly not Eraserhead (1977), and did not understand how far Lynch was willing to go. And though Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet had much in common about exposing the sordid underbelly of Small Town, America, neither project could prepare casual fans for the shotgun-in-the-face that was Wild at Heart.

At Cannes, Wild at Heart received an equal helping of boos and cheers upon its debut, commonplace among Cannes winners. But critics could not put too fine a point on their feelings about the film, often resulting in dismissive statements. Roger Ebert, who was described as “pink with outrage” when Lynch’s film won the Palme d’Or, and who famously admitted he could not get his head around Lynch’s films, wrote, “There is something repulsive and manipulative about it, and even its best scenes have the flavor of a kid in the school yard, trying to show you pictures you don’t feel like looking at.” Jonathan Rosenbaum, writing for the Chicago Reader, similarly noted the film’s immaturity, calling it “exploitation fodder that seems to come straight out of junior high.” Newsweek critic David Ansen put his critique in a more cool-headed manner: “Lynch is opportunistically trafficking in Lynchian grotesqueries. The mannerisms threaten to overwhelm the matter… It’s yet another journey inside Lynch’s seething subconscious, an exciting place to visit but one that is beginning to show its limitations.” And more than once, Lynch was accused of parodying himself for the sake of his then-popular status.

The French critics were far more favorable, reading the film as a critique of violence in America or a society on the verge of self-destruction. They were right about the latter part, anyway. But Lynch demonstrates an evident fondness for the film’s central lovers, Sailor Ripley and Lula Fortune, played to unbridled perfection by Cage and Dern. Sailor, a descendant of Elvis in a snakeskin jacket, claims his garb “represents a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom.” He has chain-smoked since the age of 4 and, in the first scene, beats a man to death with his bare hands. The victim was hired by Lula’s mother, Marietta (Diane Ladd, Dern’s real-life mother), to kill Sailor after he turned down her proposal to “fuck Lula’s ma-ma.” Following a stint in prison for manslaughter, Sailor resolves to break parole and take Lula on the road to California, stopping in cheap motels, taking in the occasional metal band, and humping like rabbits. At the same time, Marietta has ordered her sometimes-lover, Johnny Farragut (Harry Dean Stanton), to track Lula down and bring her daughter home. But she also hires a gangster named Santos (J. E. Freeman) to kill Sailor and recover Lula, even though it means Santos gets to kill Johnny as well.

Soon enough, Sailor and Lula find their way to Big Tuna, Texas, a dumpy little town populated by a variety of scum, the king of them being Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe). With Sailor out of money and Lula newly pregnant, Bobby is able to convince Sailor to take part in a feed store robbery. Of course, the robbery goes south, resulting in Bobby’s death and Sailor’s capture. Sentenced to five years in jail, Sailor bides his time, while on the outside, Marietta, still enraged by her rejection, mourns his release. When he’s eventually freed, he’s met by Lula and their son. But Sailor vows to leave Lula and their child because he’s not good enough for them. Before he gets too far, Sheryl Lee appears as The Wizard of Oz‘s Glinda the Good Witch (played by Billie Burke in the original) and tells him, “Don’t turn away from love, Sailor.” Convinced he’s had an epiphany, Sailor runs back to Lula and their boy, stomping on top of cars stalled in traffic, and finds his love. There, on the hood of their car, he sings Lula a rendition of Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender”—the song Sailor vowed only to sing to his wife.

But this plot description says nothing of the oddities found throughout Wild at Heart. There’s Mr. Reindeer (W. Morgan Sheppard), the mobster hired to kill Sailor, who employs an impressive sampling of Lynchian weirdoes. Among them is Juana Durango (Grace Zabriskie), whose daughter Perdita (Isabella Rossellini) is Sailor’s ex-girlfriend, who’s sleeping with Bobby Peru. There’s also a darkly comic aside involving Lula’s memories of her cousin Dell (Crispin Glover), a Christmas-obsessed wacko with cockroaches in his underpants. Let’s not forget when Sailor and Lula attend a concert by the metal band Powermad, and Sailor halts the show to sing Lula his take on Elvis’ “Love Me.” Lynch adorns this moment with the faux screams of teenage fans of the hysteric, fainting, Beatlemania variety. It’s a hilarious and odd moment that puts us in the middle of Sailor and Lula’s relationship, which is all manner of flawed and messed up, but it also happens to be rather endearingly unhinged.

With Lynch’s pervading theme about the ugly underbelly of America running through Wild at Heart and other films, he emphasizes that theme with allusions to The Wizard of Oz. He did something similar in Blue Velvet, in which Isabella Rossellini plays Dorothy, a woman whose husband is killed and her child kidnapped by psychotics—she’s not in Kansas anymore. That classic 1939 gem represents a fairy tale world where all one has to do is click her heels to wake up from a bad dream. Lula tries that very thing after Bobby Peru assaults her with a horrifying rape-by-voice. In a revolting scene, Bobby comes on to Lula, who resists; he grabs her throat and says he’ll leave if she’ll just say “fuck me.” Over and over again, Bobby whispers, “Say ‘Fuck Me,'” until Lula, taken by the low-level, high-intensity eroticism of the moment, concedes. When she does, Peru steps back and says, “No thanks, I don’t have time today. I’ve got to go!” The violation is absolute. Lula’s power and confused sense of rejection in this scene remain traumatic for both the viewer and Lula. If only she could click her heels and get away.

The references to The Wizard of Oz occur in the dialogue and about a dozen visual nods. The symbolism completes the notion that Sailor and Lula have lost themselves in a fantasy world of violent Americana. Sailor’s snakeskin jacket, flashy red car, and Elvis obsession speak to his fantasy, whereas Lula seems more self-made and free-spirited but no less American. That Sailor and Lula are so committed to each other to fantastic extremes, despite the insane world around them, is the very meaning of Wild at Heart—represented by the fire that not only killed Lula’s father but also signifies their love. It’s also the reason Lynch changed Gifford’s ending from Sailor leaving Lula to a happy one that better reflected their relationship’s mutual fire, burning through the film with the image of flames and struck matches. (The only possible alternative to Sailor and Lula burning on forever is both of them going out at once, perhaps in a fire, an equally romantic idea.) Lynch also reinforces Sailor and Lula’s passion with unbridled sexuality between them. They seem perfectly attuned and open to any sexual experience, including erotic tales of their respective former conquests, and remain in sync that way throughout the film.

Wild at Heart opened up movie violence to independent cinema. Lynch brought a new, visceral, figurative violence to the screen with his film. He gave other independent filmmakers—such as Quentin Tarantino with his 1992 debut Reservoir Dogs—a new license to depict violence as extreme and cinematic. Filmmakers could now paint art with blood. Lynch described the book as “exactly the right thing at the right time,” and that’s what his film ended up being, whether critics at the time were willing to admit it or not. In many ways, Wild at Heart reflects a society ready to burst and stands as a precursor to the 1992 riots in Los Angeles. “I’ll tell you what it is,” Lynch told interview Chris Rodley. “Each year we give permission for people to get away with more. We do it by being disorganized, being without leadership, not making decisions fast enough, and not holding true to thinking that were in place to begin with. Then it gets easier to give more away.” Wild at Heart considers an America where everything has been given away. The film shows an underworld already saturated in violence and, with the emergence of Sailor and Lula, pours over into popular culture with hints of Elvis Presley and The Wizard of Oz.

Lynch intimates how those confused qualities of light and dark linger under the surface, festering under the skin like a spider sack waiting to hatch. For Lynch, Wild at Heart was “a picture about finding love in hell.” Part of creating that hell was exaggerating violence to surreal, ugly extremes. But to counteract the ugliness he puts onscreen, Lynch also exaggerates Sailor and Lula’s love, their love-making, and their idiosyncratic caricatures, each played to outlandish precision by Cage and Dern. To be sure, the film is a frenzied interpretation of an American love-on-the-run tale through Lynch’s eyes. As a visual artist and filmmaker, Lynch was not so much trying to be himself in 1990; rather, he filtered Gifford’s novel through his own unique, often disturbing, often extreme perspective. There’s always a hint of irony, humor, and macabre in Lynch’s works, and accepting Wild at Heart as a flame-fueled story in a Lynchian technique helps to not only understand the film’s harshest critics but also celebrate the very qualities they condemn.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review