Wicked Little Letters

By Brian Eggert |

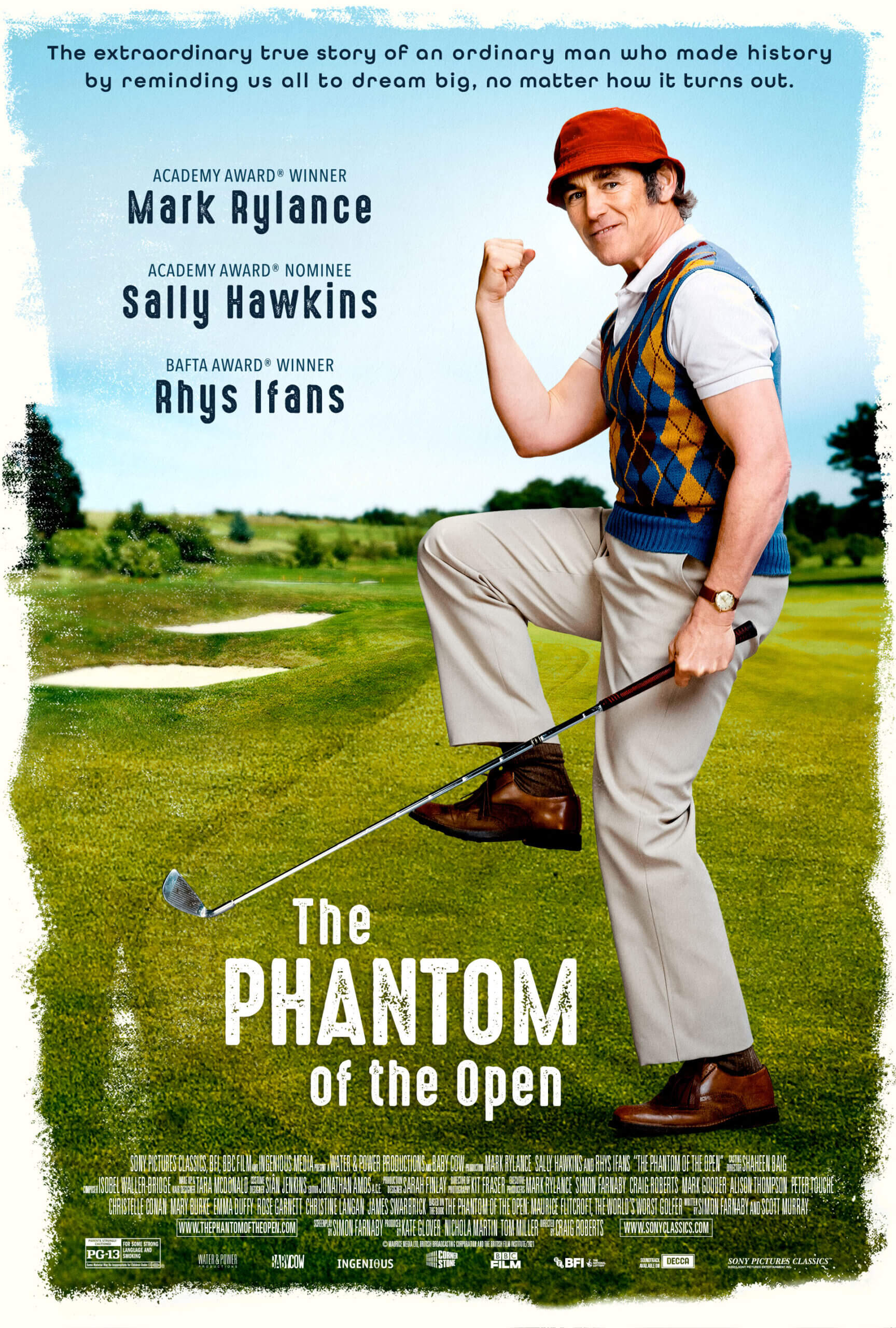

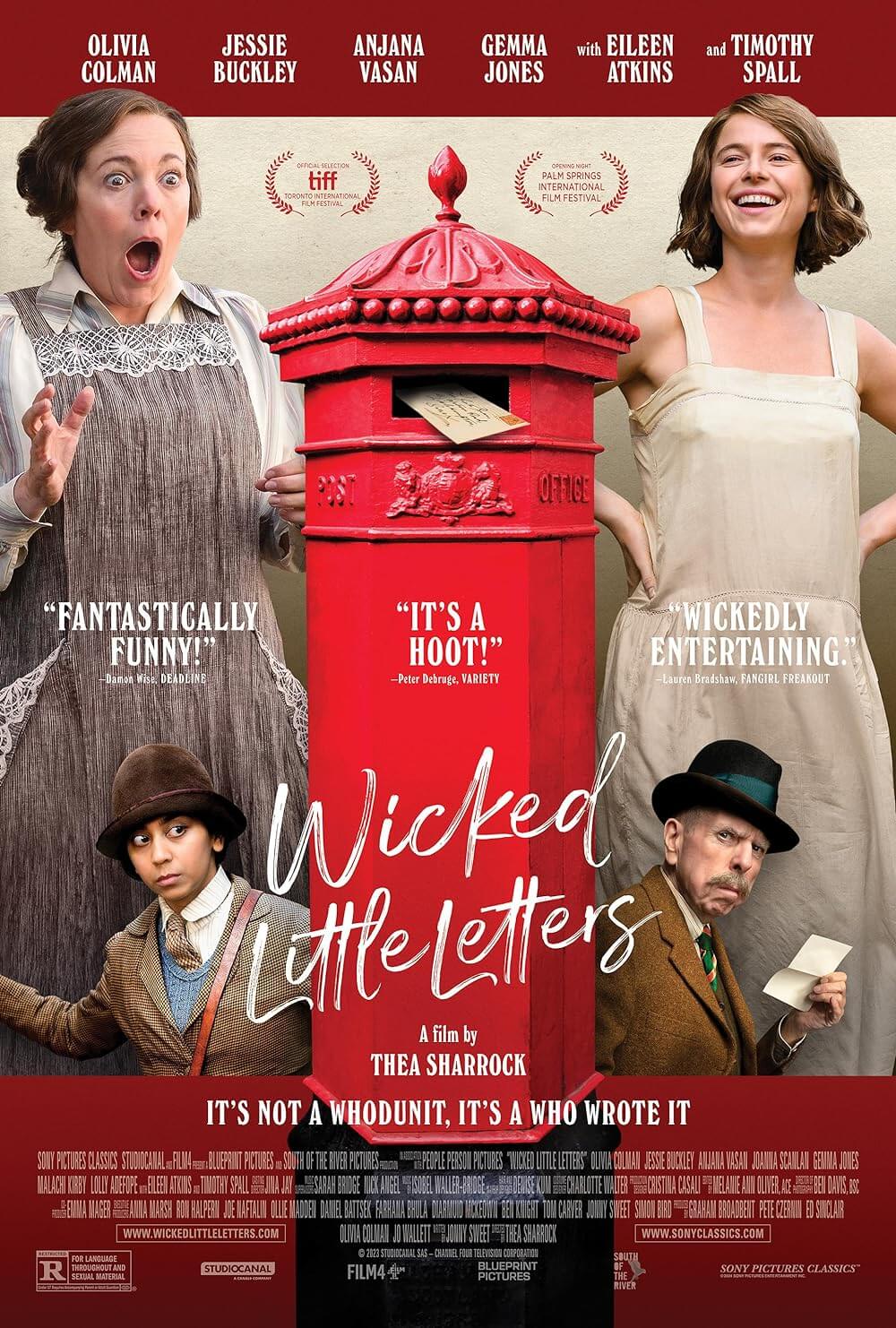

Before people left vitriol in the comments under a shroud of online anonymity, they could write anonymous poison-pen letters and call the recipient names or expose their secrets. Postmarks and handwriting supplied the only clues as to the sender. There’s a great film on the subject by French master Henri Georges-Clouzot called Le Corbeau (1943), a grave thriller meant to capture the effect of fear and paranoia experienced under the German occupation during World War II. Wicked Little Letters has lower stakes, offering a blithe, foul-mouthed British tale in a familiar but welcomed manner of import from Sony Pictures Classics. Admittedly, I’m a sucker for this sort of comedy of (bad) manners, where someone’s unruly behavior undoes a proper English town, exposing the disingenuous nature of decorum. And this one has a terrific cast: Olivia Colman, Jessie Buckley, Anjana Vasan, Timothy Spall, and Eileen Atkins. It also features worthy themes about the dangers of repression and a sly subtext about the timeless trend of accusing someone of the very thing you’re guilty of, evidenced everywhere, from social media to contemporary politics.

Based on an actual 1923 poison-pen scandal that took place in Littlehampton, detailed in the 2017 book The Littlehampton Libels by Christopher Hilliard, the production opens with a wry foreword: “This is more true than you’d think.” Comedian Jonny Sweet’s screenplay takes the usual liberties with the real-life story. He condenses and refines the incident, which unfolded over several years and four different courtroom trials. Most people will be unfamiliar with this little-known case from just after World War I, but even so, it’s not much of a whodunit, nor is it difficult to guess who’s behind its nastily worded letters. They’re delivered to Edith Swan (Olivia Colman), a middle-aged spinster who lives in a quiet Sussex parish with her doormat mother, Victoria (Gemma Jones), and domineering, possessive, prejudiced father Edward (Timothy Spall). Edward points the finger at their neighbor, Rose Gooding (Jesse Buckley), a fiery Irishwoman who swears like a sailor and delights in defying good manners, much to the offense of the Swans’ god-fearing ways.

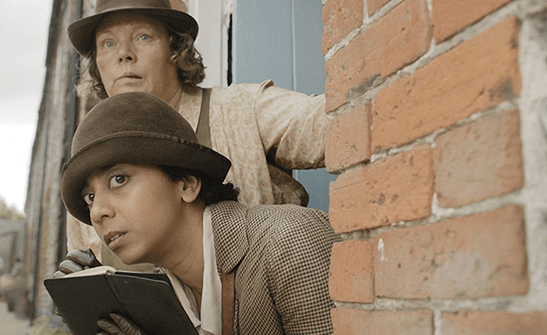

When the Swans call the local Constable Papperwick (Hugh Skinner), he sees the pious, meek Edith as the apparent victim of an unruly outsider, Rose. And so, the authorities arrest Rose on nothing more than a hunch and an unsupported accusation. She’s forced to leave her daughter (Alisha Weir) of dubious parentage—which, for her stuffy neighbors, is part of the problem—with her live-in boyfriend (Malachi Kirby) while in prison. Poor, Rose can’t afford the £3 bail. It’s all the more complicated because Edith and Rose used to be friendly—for a time, anyway—until someone, presumably Edith, called Child Protective Services on Rose for a bogus complaint. Ever since, there’s been bad blood between the Swans and Rose. Meanwhile, a new police officer, Gladys Moss (Anjana Vasan), the first female on the local force, suspects Papperwick and their superior (Paul Chahidi) may have arrested the wrong party. Despite their refusal to listen to her theory, Gladys investigates with the help of some local women (Joanna Scanlan, Lolly Adefope, Eileen Atkins) who like Rose and find Edith to be stuffy and self-important.

Wicked Little Letters takes place in a world where so-called respectable women had to pretend not to know such words, while those who did—and worse, used them—were assumed to be criminals. Then again, the letter writer’s understanding of profanity is a source of some obscure humor since the letters read as though they were written by an alien with no understanding of how to use them. The letters frequently call their recipients a “foxy ass” or “piss country whore,” though most seem baffled and bemused by such nonsense words. In the right context, swear words can be very funny. And much of the movie’s humor comes from watching stereotypically stuffy British folk having to speak long strings of explicit words while cringing, as though the sound creates a physical pain. There’s also a joy in watching Buckley verbally raze anyone who attempts to contain her character, similar to seeing how Colman’s character secretly delights in using such words and can barely contain her pleasure when asked to read them.

Wicked Little Letters takes place in a world where so-called respectable women had to pretend not to know such words, while those who did—and worse, used them—were assumed to be criminals. Then again, the letter writer’s understanding of profanity is a source of some obscure humor since the letters read as though they were written by an alien with no understanding of how to use them. The letters frequently call their recipients a “foxy ass” or “piss country whore,” though most seem baffled and bemused by such nonsense words. In the right context, swear words can be very funny. And much of the movie’s humor comes from watching stereotypically stuffy British folk having to speak long strings of explicit words while cringing, as though the sound creates a physical pain. There’s also a joy in watching Buckley verbally raze anyone who attempts to contain her character, similar to seeing how Colman’s character secretly delights in using such words and can barely contain her pleasure when asked to read them.

Director Thea Sharrock presents the story in a handsome, straightforward production, with convincing period costumes by Charlotte Walter and textured cinematography by Ben Davis, whose occasional wide-angle flourish adds to the movie’s comically heightened quality. Buckley is a bastion of humanity, energetic and alive in every scene, no matter how small. The supporting cast is also excellent, with Vasan demonstrating she could easily occupy a lead role. Gladys’ subplot about searching for the truth and facing down her ignorant male superiors is paralleled by the dynamic between Edith and her father. To that end, Spall excels at playing a hateful man who treats his fortysomething daughter like a child, complete with reprimands in the form of writing Biblical passages out hundreds of times. His scenes with Colman could play in an acidic Mike Leigh film. As for Colman, her range as Edith goes from quaint and humble to something that might remind viewers of her small role in Hot Fuzz (2007). However, Edith could have been more sympathetic had her sanctimonious behavior not been so irritating and mean-spirited.

The movie presents an odd chapter of history, where the letters spread across a whole county, and the scandal occupied an entire nation in the postwar years. But Sharrock balances the film’s often hilarious, blue-humored appeal with dimensional characters, superb acting, and a multilayered commentary about how repression will inevitably lead to an eruption. The film wags a finger at the patriarchy, the religious, and the uptight who scold others for their bad behavior in public, but behind closed doors and in their heads, they speak just like everyone else. After all, as writer Norbert Elias explored, the civilizing process is about denying common impulses, from bodily realities to the language some social circles deem uncouth. But why not embrace who we are? Wicked Little Letters acknowledges how, when there’s an attempt to contain speech or expression, it’s usually motivated by an effort to exercise power or control. Here’s a film that, rather than responding with faux offense to a silly thing like a few fucks, shits, and cocks, viewers will learn to either let it out or lighten up—but also recognize why such behavior is so antithetical to some people’s sense of control.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review