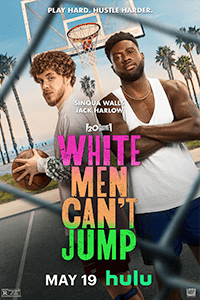

White Men Can’t Jump

By Brian Eggert |

A remake of Ron Shelton’s comedy hit from 1992, the new White Men Can’t Jump had plenty of opportunities to update its message for younger generations and reconsider the original’s thorny racial politics. While the new movie certainly dispenses with Shelton’s overarching themes—for instance, that everyone’s a little racist—it also robs its characters of personality and neutralizes the narrative’s lessons. Unfortunately, comparing the two will do the new version no favors. Director Calmatic, who helmed the abysmal remake of 1990’s House Party earlier this year, once again delivers an empty retread of established intellectual property. Both of Calmatic’s remakes show a director taking sharp and occasionally politically incorrect material and dulling its edges, rendering them flat and unmemorable—not that their political incorrectness alone made them memorable. But the new White Men Can’t Jump shows what happens when a production refuses to take risks. The remake fits squarely into the category of a hollow, low-stakes studio project made for its name-brand recognition, not because its makers had a story they needed to tell.

What made the original so unforgettable was Shelton’s unique blend of philosophy, sports, bold characters, and the distinctly 1990s Los Angeles milieu. His version started with an exhilarating 10-minute sequence, setting the stage for a foul-mouthed, trash-talking game of hustlers’ streetball, performed perfectly by Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson in their energetic prime. If you remember anything besides the hilarious Snipes and Harrelson’s love-hate banter, you’ll remember that Rosie Perez stole the movie, destroying the braggadocious male egos with her character’s trivia knowledge that earned a Jeopardy! payday, therein solving her boyfriend’s financial troubles. For the guys, it was all about winning with an angle while also betting everything on their skills, a gamble on their masculinity—in a way, the 1992 film was a movie about gambling addiction. Perez offered an alternative, more fluid outlook: “Sometimes when you win, you really lose, and sometimes when you lose, you really win, and sometimes when you win or lose, you actually tie, and sometimes when you tie, you actually win or lose. Winning or losing is all one organic mechanism, from which one extracts what one needs.”

There’s nothing so profoundly insightful or memorable about the new version. Sinqua Walls plays Kamal, a would-be college player whose anger issues have kept him grounded. Rapper-turned-actor Jack Harlow plays Jeremy, whose bad knees have kept him from playing but not hustling. They both want to compete in an upcoming championship, yet they must earn a hefty entrance fee first. Though they initially clash on the courts, given Jeremy’s motormouth and Kamal’s short temper, they soon form a working collaboration. They compete against other hoopers and hustlers in a series of basketball montages, shot in amber-hued gyms and flashy neighborhood courts by cinematographer Tommy Maddox-Upshaw. But Jeremy’s shit-talking and Kamal’s temper get them into trouble more than once, including a competitor’s retaliation with a flamethrower. Still, there’s no tension in the movie and even fewer laughs, largely because Walls and Harlow don’t have the onscreen chemistry of Snipes and Harrelson.

Screenwriters Kenya Barris and Doug Hall worked with Shelton on their story, which has none of Shelton’s punchy dialogue or thoughtful worldview. It cares even less about women. Whereas Perez was central and invariably scene-stealing—enough to argue for the movie’s feminist perspective, given its interest in women’s agency and its takedown of male egos and power—the women in the new film have less to do. Laura Harrier has a thankless role as Tatiana, Jeremy’s girlfriend, who’s tired of his hustling and has opportunities of her own. Teyana Taylor plays Imani, Kamal’s girlfriend, and after her powerhouse performance in this year’s A Thousand and One, it’s evident her talent is wasted here in a sidelined hairdresser role. Then again, neither Kamal nor Jeremy are memorable characters either. Walls plays a straight man, and Harlow has one or two amusing insults in his dull stand-up-quality material. They’re far from having resonant personalities. If there’s a silver lining, it’s that the viewer gets one more chance to see the late-great Lance Reddick in action, playing Kamal’s father, whose domineering personality left a few scars on Kamal’s psyche.

Indeed, by the humorless third act, the difficult-to-finish White Men Can’t Jump takes itself too seriously and hasn’t earned its somber tone. But given that the preceding two-thirds are bereft of laughs or dynamic characters as well, perhaps that’s true of the entire movie. Calmatic, who started in music videos and commercials, carries over a glossy aesthetic here, concentrating more on surfaces than in-depth characters or perspectives. Shelton’s original was hardly perfect, but comparing the 1992 movie with the remake leaves the viewer with a sense of the new version’s empty, commercial artlessness. The movie exists because 20th Century Studios needed “content” for their streaming service, leaving White Men Can’t Jump to debut on Hulu. Fortunately, viewers can bypass that experience and watch the original on the same service instead.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review