Reader's Choice

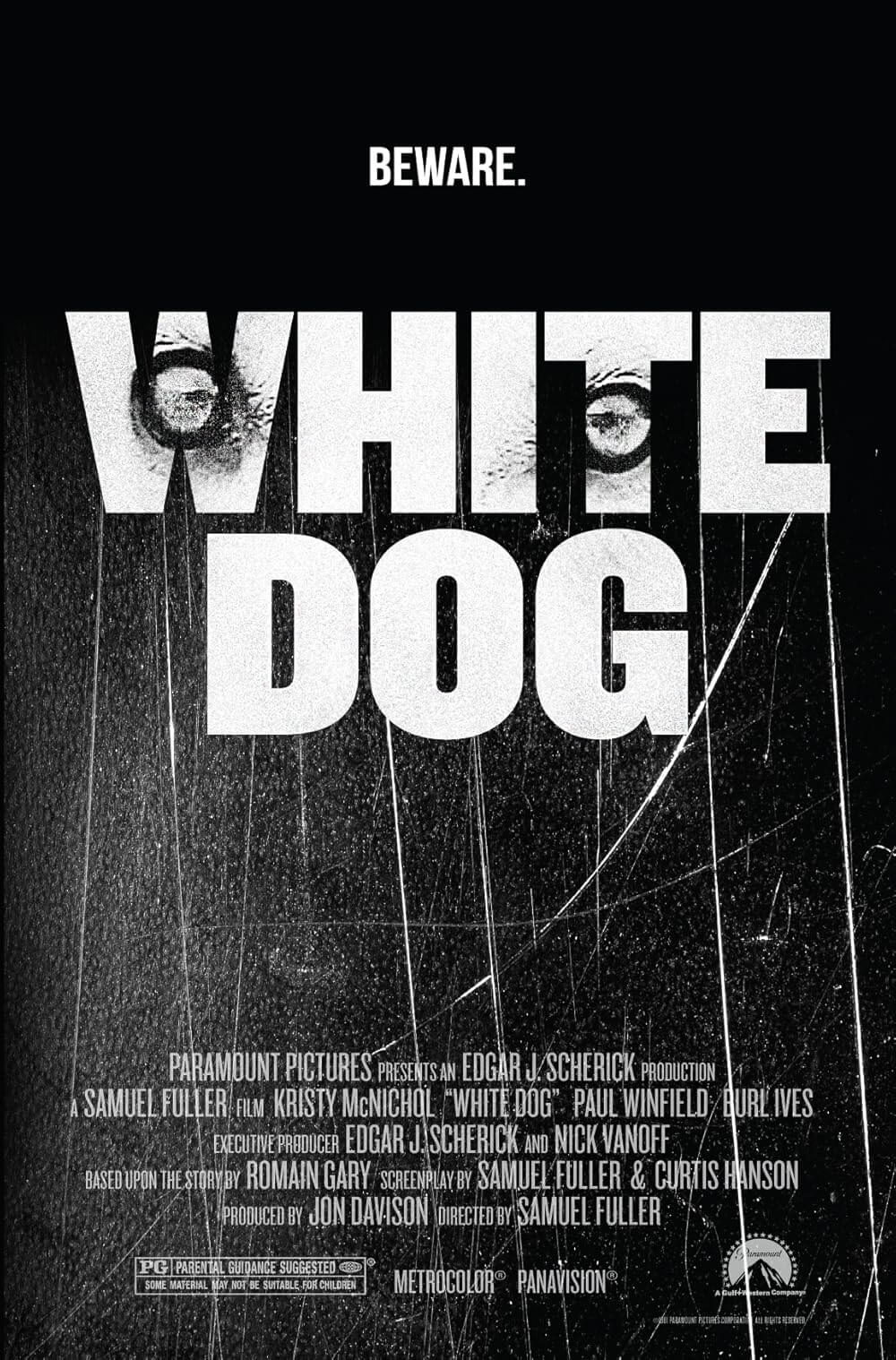

White Dog

By Brian Eggert |

Samuel Fuller’s most controversial and confronting film, White Dog, tells the story of a young woman who discovers that her adopted dog has been trained to attack Black people on sight. Determined to save the dog, she hires an animal trainer, a Black man, to deprogram it. The 1982 film never received a wide release. Paramount Pictures felt its theatrical distribution would bring about controversy, causing problems with civil rights groups. But Fuller targeted racism with his film, an unflinching and unsubtle condemnation of America’s history of prejudice and violence against people of color. Watching White Dog today, it’s preposterous to think anyone could misinterpret the film and label its message as racist. Fuller, as ever, uses the punchiness and extremes of a tabloid newspaper, telling his story with overstatement and clear-cut metaphors to make his anti-racism theme unmistakable. The opening title design epitomizes his perspective, with its black and white letters against a solid gray background, suggesting that the world is more complex and nuanced than polarized ideologies of black and white would suggest. It’s a film that could easily be critiqued for its sentimentality and bluntness, and its rough-around-the-edges execution at times. But to call White Dog racist is absurd given its lucid, surface-level commentary, as well as Fuller’s life and career of loud protests against discrimination and racial violence.

White Dog originated with the nonfiction story Chien blanc, penned by French novelist Romain Gary and published in 1970, segments of which appeared in Life magazine. In the book, Gary and his then-wife Jean Seberg adopt a white German shepherd and soon discover it has been trained as a tool for racist attacks. When they try to correct the problem, the Black trainer they hire takes revenge and conditions the dog to attack white people. Gary’s confused message, a reaction to Seberg’s outspoken support of various civil rights groups that upended their lives, would be streamlined after Robert Evans optioned the story in 1977 with Roman Polanski slated to direct. Paramount president Michael Eisner envisioned a “Jaws on paws” shocker, and screenwriter Curtis Hanson (L.A. Confidential) was tasked with the adaptation. But Polanski’s legal troubles meant the production was delayed. Paramount ordered various rewrites and circled other directors until Hanson recommended Fuller, whose decades of experience meant he could carry out the production fast and for cheap. Together, Fuller and Hanson rewrote the existing script, crafting a pointed damnation of racism in which the Black trainer was the tragic hero, desperate to remove the animal’s racist education. On a budget of $7.1 million, Fuller shot for 44 days in Los Angeles, but not without considerable studio interference that would eventually halt the film’s release altogether.

Fuller’s career is loaded with controversial topics and films that somehow made it passed studio bosses, only to be received with equal measures of critical acclaim and conservative dissension. He often worked on the margins with a shoestring budget. However, his productions made money and, as long as they continued to earn a profit, executives like Daryl Zanuck gave him the freedom to explore whatever subject he wanted. Sometimes, that got him into hot water with censors and even government officials. His spy-thriller Pickup on South Street (1953) was so critical of the FBI that J. Edgar Hoover opened an investigation into the writer-director. Elsewhere, he tackled racism, nationalism, misogyny, sex crimes, and anti-Semitism in films like Steel Helmet (1951), Shock Corridor (1963), The Naked Kiss (1964), and The Big Red One (1981). Fuller’s films always came from a place of earnestness and experience. He had seen it all as a teenager when he served as a crime reporter for a New York tabloid. Later, he served as an infantryman in World War II, where he helped liberate the concentration camp at Falkenau. Fuller’s style was bald-faced and daring, and his work on White Dog remains among his most brazen.

The story follows an aspiring young actress, Julie (Kristy McNichol), who hits a stray dog, a gorgeous white German shepherd, while driving to her home in the Hollywood hills one night. As she nurses the animal back to health and posts signs around town for the owners, she forms a bond with him. He’s gentle enough, allowing her to pry open his jaws to force down a pill. And the dog even protects her from an attempted rape by an intruder. Later, the dog goes missing after it chases a rabbit into the hills. Julie’s search at the pound leads to a desperate scene—similar to one sequence in Umberto D. (1945)—where she sees a dog cruelly destroyed. After that, she resolves to keep the stray for herself. Meanwhile, the dog attacks and kills a Black man driving a street sweeper, and later that night, when he returns to Julie, she’s overjoyed and assumes the bloodstains on his white fur are from the rabbit he chased earlier. Her boyfriend, Roland (Jameson Parker), isn’t convinced of the dog’s innocence and feels threatened more than once by the dog’s protective behavior toward Julie. It’s not until the dog attacks one of Julie’s costars, a young woman of color, that she recognizes the problem. Though, she refuses to have the dog put down, as Roland suggests, and declares her intention to have the animal “retrained” by a professional.

To this point, White Dog has been aligned with McNichol’s underdeveloped character, but Fuller’s scenario soon finds its dramatic center with its African American animal wrangler, Keys (Paul Winfield, in a powerhouse performance). Julie takes the dog to Carruthers (Burl Ives), who runs an operation that rents out lions, tigers, chimps, and bears to Hollywood productions (complete with too-small cages and questionable living conditions). Carruthers sees the problem right away—“That ain’t no attack dog you’ve got. That’s a white dog!”—and he refuses to help. However, Julie then meets Keys, Carruthers’ business partner, who has long hoped to deprogram a white dog. She agrees to leave the dog with Keys, who proceeds to lock himself in an arena-like cage and allow the dog to attack his protective padding until the animal tires and can attack no more. “I’m gonna teach you that it’s useless to attack black skin,” he explains. For Keys, it’s a matter of hope, a symbol that racist ideologies can be changed not only in this animal but the world at large. Even after the dog escapes and kills another Black male, this time in a church, and even after Julie gives up hope, Keys is determined to change the animal for the better. He has to believe he can reverse racism; it has become an obsession, albeit an ill-fated one.

Fuller’s direction is both visceral and unshakably moving, though evidence of its cheapness remains. He makes the most of his limited budget, employing creative dog point-of-view angles and arch close-ups, which suggest a menacing intelligence behind those puppy-dog eyes. Indeed, dog lovers will notice much tail-wagging during attack scenes, an indication that the canine is playing, not attacking, which dispels some of the urgency of these scenes. Moreover, Fuller used five credited dogs on the set, younger animals for attack scenes, and an older, more friendly looking canine for cuddly moments. Fuller and editor Bernard Gribble created the dog’s role in the editing room, and the dogs’ varying ages and states of play are sometimes apparent. On a technical level, there are several visible gaffes, including boom mic and camera shadows, giving White Dog an appropriate coarseness that, alongside the alternately wooden and hammy performances from McNichol and Ives, feel suitable for an exploitation film. Goofs aside, it’s evident Fuller has infused each scene with playful details. There’s more than one reference to François Truffaut, whom Fuller greatly admired, including Julie’s gift of the Hitchcock/Truffaut book to her friend as a get-well present. And if Fuller’s opinion of Star Wars and the blockbuster trajectory of Hollywood was ever in doubt, watch the scene when Carruthers throws a dart at a cardboard R2-D2 and aptly notes, “That’s the enemy!”

Fuller’s direction is both visceral and unshakably moving, though evidence of its cheapness remains. He makes the most of his limited budget, employing creative dog point-of-view angles and arch close-ups, which suggest a menacing intelligence behind those puppy-dog eyes. Indeed, dog lovers will notice much tail-wagging during attack scenes, an indication that the canine is playing, not attacking, which dispels some of the urgency of these scenes. Moreover, Fuller used five credited dogs on the set, younger animals for attack scenes, and an older, more friendly looking canine for cuddly moments. Fuller and editor Bernard Gribble created the dog’s role in the editing room, and the dogs’ varying ages and states of play are sometimes apparent. On a technical level, there are several visible gaffes, including boom mic and camera shadows, giving White Dog an appropriate coarseness that, alongside the alternately wooden and hammy performances from McNichol and Ives, feel suitable for an exploitation film. Goofs aside, it’s evident Fuller has infused each scene with playful details. There’s more than one reference to François Truffaut, whom Fuller greatly admired, including Julie’s gift of the Hitchcock/Truffaut book to her friend as a get-well present. And if Fuller’s opinion of Star Wars and the blockbuster trajectory of Hollywood was ever in doubt, watch the scene when Carruthers throws a dart at a cardboard R2-D2 and aptly notes, “That’s the enemy!”

To be sure, White Dog is pure Fuller, with dynamically composed attack scenes staged as bold cinematic showpieces. After the first attack, the street sweeper goes barreling into a shop window on Rodeo Drive, causing an explosion; in the church attack, the dog seems to look up in defiance at a stained glass portrait of Saint Francis of Assisi, the Patron Saint of Animals. Later, when the dog is loose and scavenging the streets of Los Angeles, there’s a breathless moment when he emerges from an alleyway and, at the same instant, a small Black child in the distance is saved when his mother pulls him inside a shop. In later scenes, Fuller uses a lightning storm to evoke Frankenstein (1931), associating the dog with a sympathetic monster who was created by someone even more disturbed. The screenplay also infers that the dog has a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde complex, implying that there’s good and evil inside the animal (and it’s grim foreshadowing that Keys calls the dog “Mr. Hyde”). Ennio Morricone’s excellent score—motifs of which the composer reused in his music for 1994’s Wolf, curiously enough—further emphasize Fuller’s use of broad, unapologetic symbolism. Morricone layers the material with dread, along with melodramatic flourishes reminiscent of Pino Donaggio’s work with Brian DePalma.

From the start, Paramount executives knew the material was risky, but they fast-tracked White Dog into production in spite of their reservations to avoid having nothing ready during an impending strike of both the Writers Guild and Directors Guild. Once Fuller had started shooting, the studio scrambled to minimize the story’s controversy by offering him notes, asking him to remove the racial content and make a more traditional killer animal movie—something akin to Jaws (1975), Grizzly (1976), or Orca (1977). Fuller ignored most of the notes, banned the executives from his set, and shot the script he and Hanson had written. In post-production, the studio held advanced screenings in Seattle and Denver, some of which garnered very positive responses. They opted for a limited release in Detroit in November 1982, and the poor reception led Paramount to halt any further distribution. Film festivals from London to Telluride asked the studio for a print to screen the film, but they denied all such requests at first. Instead, Paramount relegated the film to VHS and cable television in 1984. For Fuller, Paramount’s decision was the last straw. He was done with Hollywood, particularly after Warner Bros. trimmed his passion project, The Big Red One (1980), by nearly an hour prior to its release. Writing about the lack of distribution for White Dog, Fuller said in his autobiography, “It’s like someone putting your newborn baby in a goddamned maximum-security prison forever.” After his fiasco with White Dog, Fuller moved to Paris and never made another film in America.

Paramount’s decision to pull the film was doubtless a reaction to complaints from the NAACP, which worried that the film would give “the KKK and other white supremacist organizations ideas.” Winfield came to the film’s defense, calling the NAACP’s reaction “a disservice to black people” and overprotective. After all, white dogs were no secret. Fuller had learned about them when he investigated the KKK in the 1930s as a reporter; his film wasn’t teaching their hate group anything they hadn’t already known about for centuries. Fuller remarked on this very fact in the screenplay. Keys explains to Julie that white dogs had once been used in America to chase down slaves, and now they chase down Black convicts. “What about white convicts?” asks Julie. Keys gives her a loaded look, as if to allow Julie a moment to think about her question given everything she knows about America’s racist history. Fuller’s outrage over bigoted ideologies remains the most aggressive strain in White Dog, evidenced when Julie reacts to Roland’s suggestion that she put him down. “They should be put to sleep,” Julie says of the dog’s original trainer, “not the dog.” She meets the trainer in a later scene. An older man arrives at her home with his two granddaughters to pick up the animal, having seen her fliers around town. Julie confronts him: “You got two puppies there. You gonna teach ’em to be as sick as you are?” Then she addresses the confused children, “Do you know what your grandfather did to that dog? He turned that dog into a monster! A killer! Don’t you let him turn you into monsters either! Don’t listen to a damn word he says about anything! Not a damn word!”

Paramount’s decision to pull the film was doubtless a reaction to complaints from the NAACP, which worried that the film would give “the KKK and other white supremacist organizations ideas.” Winfield came to the film’s defense, calling the NAACP’s reaction “a disservice to black people” and overprotective. After all, white dogs were no secret. Fuller had learned about them when he investigated the KKK in the 1930s as a reporter; his film wasn’t teaching their hate group anything they hadn’t already known about for centuries. Fuller remarked on this very fact in the screenplay. Keys explains to Julie that white dogs had once been used in America to chase down slaves, and now they chase down Black convicts. “What about white convicts?” asks Julie. Keys gives her a loaded look, as if to allow Julie a moment to think about her question given everything she knows about America’s racist history. Fuller’s outrage over bigoted ideologies remains the most aggressive strain in White Dog, evidenced when Julie reacts to Roland’s suggestion that she put him down. “They should be put to sleep,” Julie says of the dog’s original trainer, “not the dog.” She meets the trainer in a later scene. An older man arrives at her home with his two granddaughters to pick up the animal, having seen her fliers around town. Julie confronts him: “You got two puppies there. You gonna teach ’em to be as sick as you are?” Then she addresses the confused children, “Do you know what your grandfather did to that dog? He turned that dog into a monster! A killer! Don’t you let him turn you into monsters either! Don’t listen to a damn word he says about anything! Not a damn word!”

Samuel Fuller’s hatred of hatred fuels White Dog. In her book about the director, Lisa Dombrowski wrote most succinctly about the film, calling it “Fuller’s most complete expression of his belief in the power of education to change minds, an optimistic challenge to ignorance and bigotry.” The director dramatizes racism as a condition that, tragically, cannot be so easily cured, at least not in the film’s German shepherd. In the heartbreaking final scene, Keys seems to have retrained the dog to trust people of color, save for a final test. Although the animal does not attack Keys, Mr. Hyde’s volatile deprogramming has led to a psychotic break, and he violently attacks Carruthers before leaping at Julie. With no other choice, Keys shoots the dog, and the devastating expression on Winfield’s face captures his failure to cure the animal of all its violent tendencies. By the end, Fuller has revised Gray’s novel into such a potent metaphor that the sheer force of his narrative overcomes any flaws in the film’s execution. Fortunately, White Dog has been rediscovered and reassessed in recent years as one of Fuller’s most vital works. It remains a masterpiece by a director who never minced words and always left his audience feeling the gut-punch of his cinema.

(Editor’s Note: This review was suggested and commissioned on Patreon by Brenda. Thanks for your support!)

Bibliography:

Brown, Royal S. “Review: White Dog.” Cinéaste, vol. 34, no. 3, 2009, pp. 54–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41691333. Accessed 28 Mar. 2020.

Dombrowski, Lisa. The Films of Samuel Fuller: If You Die, I’ll Kill You! Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Fuller, Samuel; Fuller, Christa Lang; Rudes, Jerome Henry. A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting and Filmmaking. Knopf, 2002.

Hoberman, J. “White Dog: Sam Fuller Unmuzzled.” Criterion.com. 27 Nov. 2008. www.criterion.com/current/posts/847-white-dog-sam-fuller-unmuzzled. Accessed 28 Mar. 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review