Whiplash

By Brian Eggert |

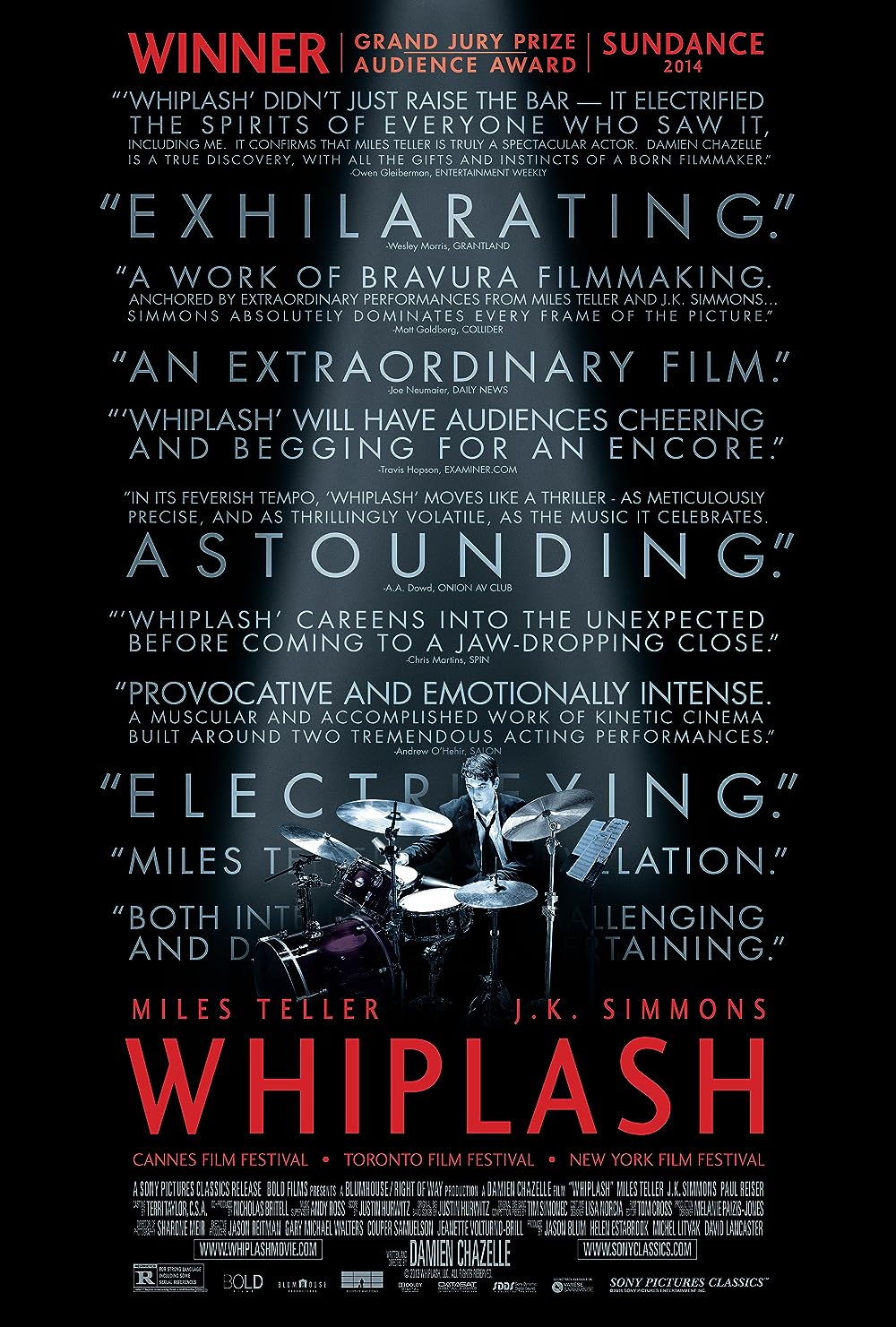

Putting everything into your art or sport of choice has been the theme of many a dramatic motion picture, but few pour out their passions with such volatile intensity as Whiplash. Writer-director Damien Chazelle follows up his black-and-white debut feature Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009) with his 2014 Sundance Film Festival favorite, which took home the Grand Jury Prize and the Dramatic Audience Award. Headed by his two central actors, Miles Teller and J.K. Simmons, Chazelle’s fascinating jazz-centric film considers whether an instructor’s psychological and even physical abuses of his students are worth the turmoil if his cruelty results in artistic genius. Certainly, our supportive, sensitive society would not agree, whereas, those passionate about art, specifically jazz, know that some of the finest masterpieces come from lives defined by struggles the artist sometimes does not overcome.

If R. Lee Ermey’s drill instructor character in Full Metal Jacket had attended the jazz program at Manhattan’s prestigious Shaffer Conservatory, he would have been sent home crying, his tail between his legs, thanks to the top instructor, Terence Fletcher (Simmons), who affirms at one point, “There are no two words more harmful in the English language than ‘good job.’” His head shaved bald, his clothes all black, and his shirt pulled tight against his toned frame, Fletcher is an intimidating man whose acerbic bark gives way to a scathing bite. In one sequence, he humiliates an out-of-tone student to tears and then kicks the boy out of class; once the boy leaves, he admits to the class the boy’s tone was fine, but the fact that he didn’t know he was in tune was a problem. Such demonstrations, topped with a healthy dose of verbal berating, come standard in his class. Enter quiet, talented, 19-year-old jazz drummer Andrew Neyman (Teller), whose goal is not only to become great but to become one of the greats.

Andrew is an absolutist, and his all-or-nothing approach is polarized between 1) transforming himself into the next Buddy Rich, Hank Levy, or Charlie Parker, and 2) leading a life devoid of meaning. For option 2, Andrew hears a story about one of Fletcher’s former students that committed suicide, supposedly because of mental scars left over from his abuse. And so, obsessively, Andrew practices on his skins, his sticks leaving open sores on his hands. He endures every abuse Fletcher doles out, and his insults only make Andrew work harder. Coming from a line of unexceptional people—his father (Paul Reiser) is supportive to a fault—Andrew is determined to push himself further. Chazelle’s script is supremely focused on Andrew, whose confidence grows enough to ask out a concessions girl (Melissa Benoist) at a nearby movie theater. Shortly after their first date, he tells her that in order to become a great drummer, he must expel any distractions from his life, and she’s a distraction.

Andrew’s logic is calculated, and unfeeling; he puts all of his passion into his drums, and he knows nothing would be left for anyone else. As a result, Andrew avoids his fellow students and remains so focused on his ambition that he isolates himself—all of these traits not unlike the virtuoso mind of Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. Losing himself in tears and furious bursts of anger and frustration, not to mention pounding up to 300-beats-per-minute on his drums, Teller astounds in his intensity and range. Most impressive is how well the actor learned to play the required pieces for his role; although, he maintains a level of naiveté throughout that makes his character not only socially awkward but infatuated. A dangerous mix. Nevertheless, J.K. Simmons outshines even Teller’s performance with his manipulative, secretly vulnerable, yet monstrous role. After all, he starred in Chazelle’s 18-minute short that premiered at Sundance in 2013, whose praise provided the inspiration to turn Whiplash into a feature-length film.

Some might argue otherwise, but Chazelle fails to explore Fletcher to a sufficient degree and what causes him to unload on his students. He’s nonetheless a fascinating character who proves a controversial argument—that, under the right circumstances, an established talent can become a genius if pushed to do so. However divisive a notion it may be for those who refuse to believe practice-makes-perfect and genius is born, not trained, Chazelle delivers a compelling drama. Without an overt sense of style—aside from sharp cutting during the performance sequences—the straightforward direction demonstrates Chazelle’s control over the material. And jazz aficionados, even those merely diverted by jazzy sounds, will find Chazelle’s music selections, from the titular Levy tune to “Caravan” by Juan Tizol and Duke Ellington, infectious, adding undeniable momentum to this potent, superbly acted drama.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review