While We’re Young

By Brian Eggert |

As everything old becomes new again, everything new becomes unfashionable, and those who thought they were modern for keeping up with the latest trends, they find themselves to be old news. Such is the intergenerational crisis that afflicts the middle-aged; specifically, a conflict that swells between today’s once-defining Generation X-ers and the emergent millennials. It’s also the subject of Noah Baumbach’s While We’re Young, a comedy about a pair of fortysomething New Yorkers who, after spending time with a twentysomething couple, feel equally revived and uncomfortable in their own skin. The conflict reminds one of Baumbach’s Greenberg (2010), in which the titular, middle-aged narcissist rants about youth: “The thing about you kids is that you’re all kind of insensitive… You’re just so sincere and interested in things. There’s a confidence in you guys that’s horrifying… You wouldn’t know agoraphobia if it bit you in the ass, and it makes you mean… I hope I die before I end up meeting one of you in a job interview.”

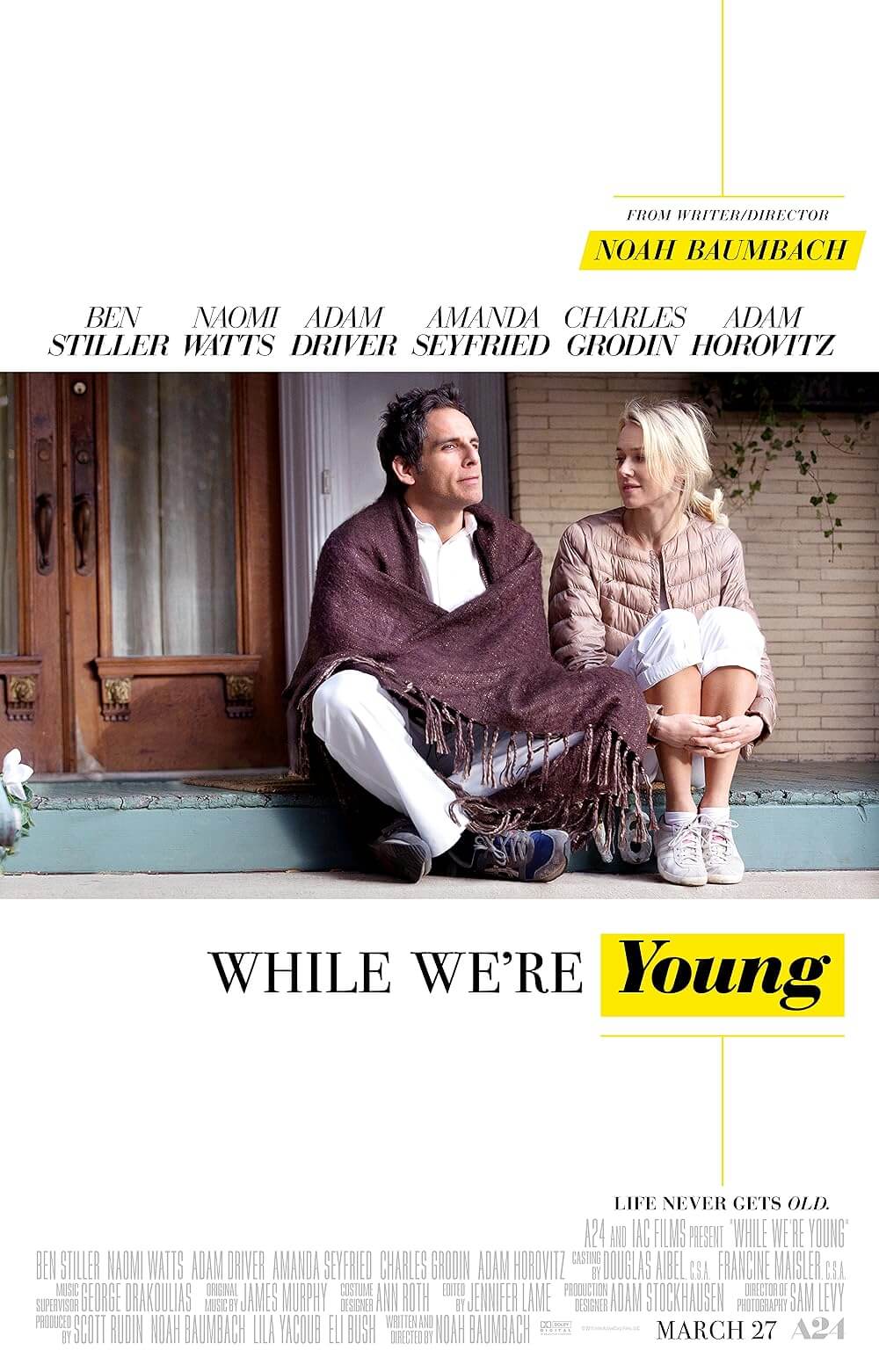

In While We’re Young, Ben Stiller, who gave that speech in Greenberg, and Naomi Watts play the married couple, Josh and Cordelia. He’s a struggling documentary filmmaker who never lived up to his potential, and she’s a doc producer. Together, they have given up on having children after a series of miscarriages, while their older friends Fletcher (Adam Horovitz, aka Ad-Rock of the Beastie Boys) and Marina (Maria Dizzia) are consumed by the alienating parenthood cult. Josh and Cordelia befriend Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried), a married pair of hipsters who could be their children, and who seem to occupy space on a much cooler plane of existence. Each of the characters is the product of a careful, hilarious, and accurate observation on Baumbach’s part. There’s a telling scene where the foursome tries to remember the word “marzipan”. Josh wants to use his smartphone to find the answer, but Jamie proudly suggests, “Let’s just not know it.” Whether it’s wise or a pretentious affectation on Jamie’s part, Josh is impressed enough to adopt his younger counterpart’s personal style, including a short-rimmed fedora.

For much of the film’s first half, Baumbach outlines the couples’ differences, particularly in one clever montage: Jamie and Darby watch old VHS tapes, listen to vinyl, and use typewriters. Josh and Cordelia stream Netflix, listen to CDs, and spend dinners lost in their smartphones. Jamie and Darby accept the high and low equally, while Josh and Cordelia have firm opinions. Darby makes avocado-almond ice cream at home, and Jamie wants to be a documentarian. Cordelia works alongside her father (Charles Grodin), a famous doc-maker compared to Frederick Wiseman and Albert and David Maysles. Josh, who has struggled for eight years to complete his latest project, feels reinvigorated by Jamie’s enthusiasm. But it’s more than just youthful vigor that interests Josh and Cordelia; it’s feeling relevant again and filling their time with active projects and ever-present creativity. Despite having no real obligations to hold them back, Josh and Cordelia feel pinned down. Josh rationalizes their lifestyle in a heartbreaking statement: “Maybe the point is that we have the freedom. What we do with it isn’t important.” Somehow, going to a “street beach” and hallucinogenic Ayahuasca ceremony seems more alive than their comfortable marriage.

Baumbach could not have picked a better actor than Stiller to play Josh, as the actor epitomized what it means to be a member of Generation X with his own film Reality Bites (1994). When Stiller played the self-absorbed character in the aforementioned Greenberg, he lashed out at youth for his own missed opportunities. Baumbach poses Josh against Jamie, who is both charming and duplicitously realized by the emergent Driver, and through them, the writer-director creates a film that considers middle age largely from the male perspective. Baumbach spends less time with Cordelia and her crisis of parenthood than with Josh’s professional woes, while Darby’s role feels underdeveloped and fully devoted to supporting Jamie. It’s less a shame than a missed opportunity on Baumbach’s part to explore his female characters better, if only because Seyfried and especially Watts happen to be quite fascinating and funny in their roles. When Cordelia unwittingly follows Darby into a hip-hop class, Watts demonstrates her rarely explored knack for physical comedy (see also I Heart Huckabees).

In amassing his dependably insightful filmography around characters who say what they think without hesitation, Baumbach is growing to become a modern equivalent of Woody Allen in the eighties. Baumbach, at once film-savvy and attuned to the existential timbre of his characters, explores intellectual sources within accessible comedies. Consider how While We’re Young opens with an exchange in quotes from Henrik Ibsen’s The Master Builder. The play’s character Solness recoils from the presence of youth at his door, with all their energy and directness. His much younger neighbor Hilde recommends he embrace youth. “Open the door and let them in,” she says. Elsewhere in Baumbach’s film, Josh struggles to complete an exhaustive documentary whose purpose he cannot summarize, and whose subject is a “boring” old philosopher. The character cannot help but recall Woody Allen’s character in his film Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), whose impenetrable subject is pushed aside in favor of a more commercial concept. Jamie’s doc idea begins with Facebook and ends with the conflict in the Middle East.

When the story devolves into a question of Jamie’s authenticity as an artist and a person, or lack thereof, While We’re Young seems to lose its nebulous observation of the generational gap and instead relies on a series of somewhat conventional situations, culminating in a predictable climax. Nevertheless, much like Allen, Baumbach’s poignant dialogue and wry examination of people cannot help but inspire us to consider our own relationships, friendships, and attitude toward the world—no matter how commercial or audience-friendly it may become. Moreover, Baumbach seems to admit that there’s a limitation to his material. Each of his films, from The Squid and the Whale (2005) to Margot at the Wedding (2007) to Frances Ha (2012), has some autobiographical strain. And while embracing himself in his art, occasionally catering to the audience isn’t the worst crime for an artist. Of course, references to Allen, Ibsen, and others could hardly be seen as commercial, but general audiences will enjoy While We’re Young, perhaps more than his other work.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review