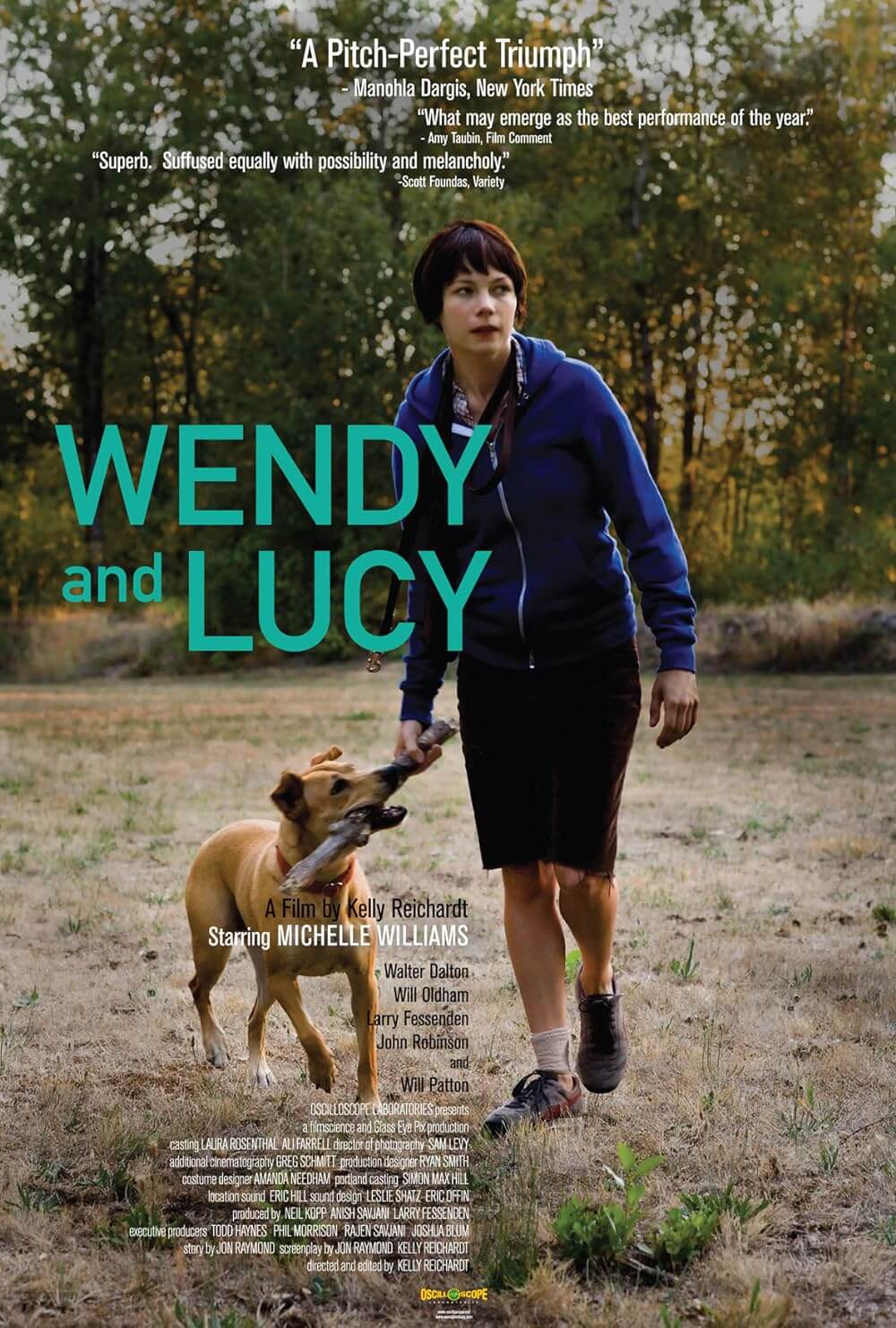

Wendy and Lucy

By Brian Eggert |

Wendy and Lucy confirms Kelly Reichardt’s place as a true original operating on the margins of American independent cinema. Though her debut River of Grass (1994) and belated follow-up Old Joy (2006) made waves among many who recognized her almost experimental approach, it was her third film that announced her work as that of a developing auteur. How fitting that her characters often inhabit the outskirts of social and economic hierarchies—American systems that dismiss or oppress those who attempt to carve out a better existence for themselves, ignorant or defiant of the prevailing authority that exploits them. Wendy and Lucy charts the troubles of a young woman played by Michelle Williams, whose poverty derails her journey to Alaska for stable employment. Accompanied by her dog, Lucy (Reichardt’s actual dog), Wendy finds herself waylaid in an Oregon town, where everyone’s just trying to do the best they can. Based on the short story “Train Choir” by Reichardt’s regular collaborator Jonathan Raymond, the film was conceived in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and released just a few months after the 2008 financial crash. It was a response to stories about people forced to help themselves without assistance from the government or some charitable organization, exploring how people of a particular socioeconomic class aspire to something more, though in most cases, the systems in place prevent them from ever escaping their situation.

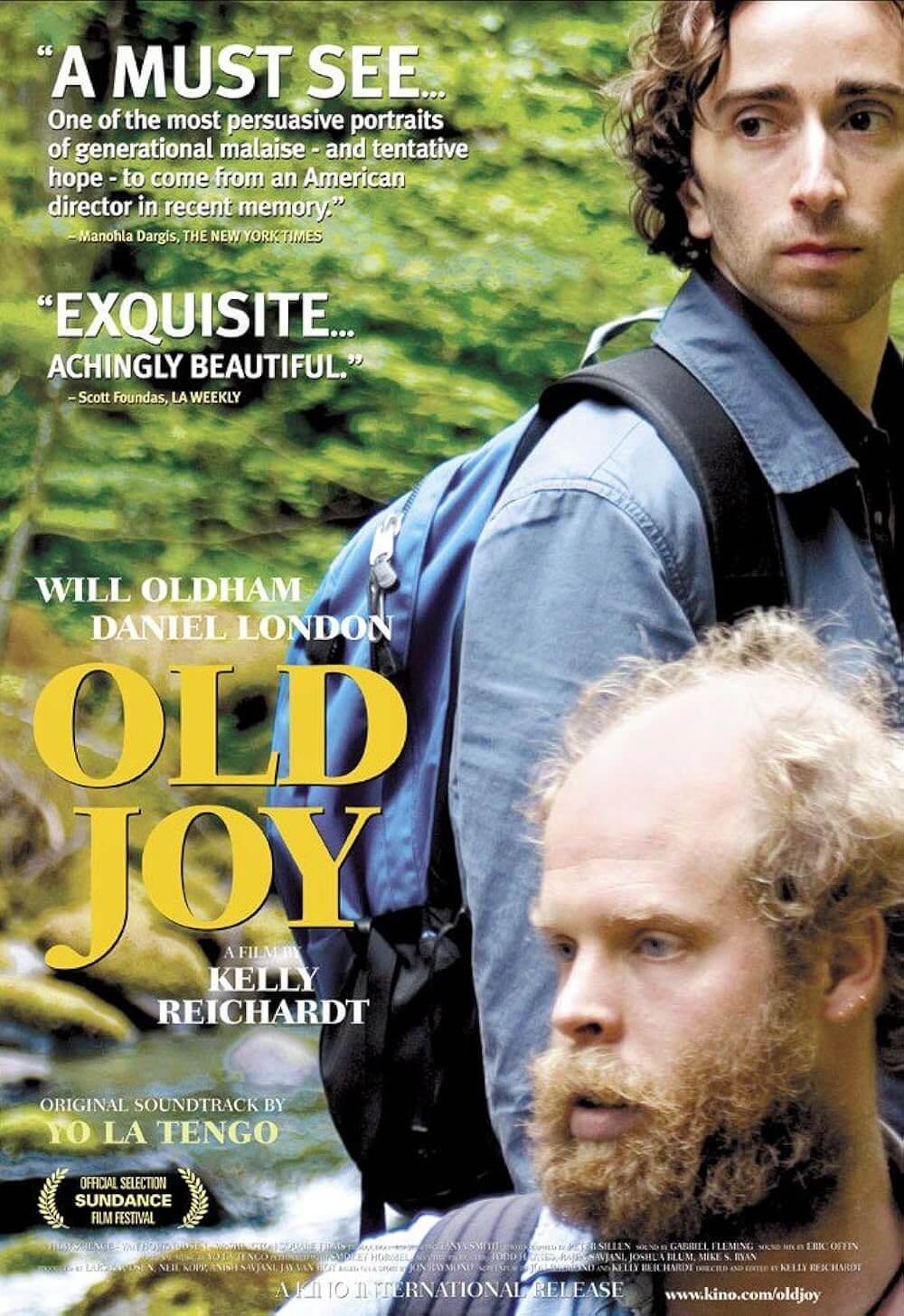

The film could be described as using familiar, reductive genre tropes, such as a girl-and-her-dog story or a road movie. Reichardt’s first four features are road movies: River of Grass offers an alternative take on the lovers-on-the-run subset of road movie; Old Joy features two friends searching the road, and the wilderness, for an elusive hot spring; and after Wendy and Lucy, Reichardt released Meek’s Cutoff (2010), about a wagon train lost on a supposed shortcut to the Oregon Trail. Each of these is a hopeless kind of road movie that offers little optimism about its characters’ fates. In an interview with the Washington Post, filmmaker Todd Haynes, who executive produced Wendy and Lucy, described Reichardt’s cinema: “Her films are all sort of failed road movies […] about people setting out across expanses and getting stuck in one way or another, emotionally or physically.” Similarly, scholars Katherine Fusco and Nicole Seymour note that unlike traditional road movies, which unfold between Point A and Point B on a quest of discovery and betterment, Reichardt’s characters find themselves “spinning their wheels.” Indeed, Wendy makes scant progress in the small Oregon town where the film takes place. Though her passage from Indiana to Alaska, where she hopes to find work at the Northwestern Fisheries cannery that’s rumored to pay well and comes with room and board, is implied; it’s presumed by Wendy’s Indiana license plates and her state of “just passing through.” The entire film takes place on a stop on a much larger expedition.

The screenplay by Raymond and Reichardt does not allude to the impetus of Wendy’s desperate travels, though her youth is evident. In her notebook, where she keeps an accounting of her meager finances, we see flowery doodles and ornamentation she has sketched with a pen. One night, she stops in a Walgreens parking lot to sleep in her car. She’s awakened the next morning by a security guard (Walter Dalton), who asks her to remove her vehicle from the lot, but she discovers the car will not start. She pushes the car to the street, just in sight of the security guard posted outside. With her supplies low and the unexpected costs of a car repair coming, Wendy knows her tight budget will not allow for expenditures such as food or meals for her dog. She shoplifts her morning meal and cans of dog food, but she’s caught by Andy (John Robinson), a smug teenage grocery clerk who, we learn later, must be driven to and from work via station wagon by his mother. Reichardt carefully delineates the sense of cruel superiority among those a step higher on the economic ladder. Andy seems eager to exact justice on Wendy for her few dollars of stolen items, and he pressures the grocery store manager to explain, “We have a policy,” as if such things mattered. When the police drive Wendy away for processing, there’s a stomach-churning shot of Lucy framed in the patrol car’s rear window, tied to the bike rack with her leash where Wendy left her, getting smaller as the car pulls away.

What follows in Wendy and Lucy is a process of necessary action, as Wendy waits for bureaucracy to take its course and then searches for her dog. Reichardt’s films dwell on matters of process, from the long slog of Meek’s Cutoff to the elaborate plot laid out by eco-terrorists in Night Moves (2013). And so, Wendy quietly endures the fingerprinting, mug shots, and solitary cell before she is released from jail, having been forced to pay $50 for the offense. She searches for Lucy at the grocery store but finds that she is gone. She visits the pound and walks down a hallway lined with cages, each housing a single dog, fed and cared for, yet each appears eager for companionship. At least they have shelter and food; the same cannot be said for Wendy, who must wash in gas station restrooms and factor every dollar into her route. Wendy also discusses her car’s situation with a nearby mechanic (Will Patton), and she must sleep in the woods as the shop keeps her vehicle overnight. She never seems to realize that her trip has been poorly planned and will inevitably fail, although Reichardt implies as much in a moment when Wendy walks passed a wall that reads “Goner” written in graffiti, a warning sign that Wendy does not heed. This should not suggest that Wendy will die or anything so overt. But when Wendy finds Lucy, who has been moved from the pound to a foster family, she resolves to leave her there. Wendy then scuttles into a boxcar that she hopes will take her to Alaska. However, the film does not end with Wendy’s arrival at her destination; the viewer never sees the train leave the Oregon town.

Reichardt shows a continued interest in the economic wastelands of the Pacific Northwest, almost as much as she’s drawn to characters on the fringes of so-called normal society. She captures them in open-air settings, using Sam Levy’s naturalistic camerawork to minimalist and naturalistic effect. Though the screenplay doesn’t reveal the source of Wendy’s desperate need to work in Alaska, the immediateness of every moment makes her trip feel like an escape. She carries her money on a strap around her torso and proves wary about making connections or even friendships. She hesitates to borrow the security guard’s cell phone to call the pound for updates, worrying about what he might want in exchange. Still, she comes to find some safety in the familiarity of the Walgreens parking lot. It’s a sly commentary by Reichardt on the false sense of security implanted by capitalistic institutions, and how Wendy continues to have faith in such institutions despite her current predicament. There, at least, she meets the kindly security guard who slips her some cash upon their farewell, trying to hide the gift from his girlfriend. “I don’t want her to know about it,” he explains. As the couple drives away, Wendy looks at what she’s been given, and the moment’s poignancy reveals itself in the crumpled fiver and few one-dollar bills. Despite meeting such a Good Samaritan, Wendy has good reason to feel reserved. Reichardt hints at this when a rambling drifter (Larry Fessenden) interrupts Wendy’s sleep in the woods. His presence is threatening; given another minute or two, he may have attacked or sexually assaulted her. Wendy has a survival instinct—she has prepared herself, though it’s no less traumatic. When she escapes Fessenden’s character, she finds some safety behind the locked door of the gas station restroom, and she breaks down. But these tears come from someone who seems to remember something far worse than what just happened.

Michelle Williams has rarely been better than her performance in Wendy and Lucy. Her portrayal is full of internalized trauma and dread, interpreted from a face that rarely evokes emotion in the presence of others. Moments that could be played at a heightened pitch—such as when the cop drives Wendy away from Lucy, and the officer disregards Wendy’s remarks that her dog is tied up outside, but she does not protest—have a silent outrage to them. Similarly, the young officer who takes Wendy’s fingerprints, and then must take them again because he did it wrong the first time, delaying her from returning to her canine companion, receives no objection. Moreover, Wendy seems to view herself as outside of her situation; the present moment is merely another obstacle to her Alaskan destination. As a result, she doesn’t identify with others like her—the poor security guard; the homeless gathered around a campfire; the line of folks at the recycling center, waiting to get their cans exchanged for a few bucks. Rather than waiting in line to exchange the few cans that she has gathered, she gives them up to a man in a wheelchair, as if to say, You need them more than I do—though, she needs the change just as badly. Her character recalls the couch surfer Will in Old Joy, a vagabond who belongs nowhere yet searches tirelessly.

Michelle Williams has rarely been better than her performance in Wendy and Lucy. Her portrayal is full of internalized trauma and dread, interpreted from a face that rarely evokes emotion in the presence of others. Moments that could be played at a heightened pitch—such as when the cop drives Wendy away from Lucy, and the officer disregards Wendy’s remarks that her dog is tied up outside, but she does not protest—have a silent outrage to them. Similarly, the young officer who takes Wendy’s fingerprints, and then must take them again because he did it wrong the first time, delaying her from returning to her canine companion, receives no objection. Moreover, Wendy seems to view herself as outside of her situation; the present moment is merely another obstacle to her Alaskan destination. As a result, she doesn’t identify with others like her—the poor security guard; the homeless gathered around a campfire; the line of folks at the recycling center, waiting to get their cans exchanged for a few bucks. Rather than waiting in line to exchange the few cans that she has gathered, she gives them up to a man in a wheelchair, as if to say, You need them more than I do—though, she needs the change just as badly. Her character recalls the couch surfer Will in Old Joy, a vagabond who belongs nowhere yet searches tirelessly.

There’s a false sense of hope in the final scenes when, after a daunting and stressful 80 minutes, Wendy at last finds Lucy at her new foster home. She tosses a stick a few times for her friend, kisses her through a chain-linked fence, and says goodbye. It’s a scene that leaves the viewer in tears, especially if you’re a dog-lover. At the very least, Lucy will be cared for—and perhaps that’s enough of an ending. But Wendy’s future proves uncertain, even hopeless. “People see the ending as having hope,” Reichardt told fellow director Gus Van Sant in an interview in BOMB. “I don’t see that much hope.” If Wendy somehow makes the trip to Alaska, what’s there for her? A well-paying job? Affordable room and board? Earlier in the film, she meets a group of drifters, and among them is a man (Oldham, no less) who worked at the cannery and boasts of its wages—regardless of the opportunity, he still ended up homeless and wandering. Wendy and Lucy leaves the dog safe and tended to, but the ending is not hopeful; Wendy has abandoned the one creature that loves her unconditionally to fulfill an unfulfilling dream. Worse, there’s no sense that, if the story were to continue, Wendy would return to reconnect with Lucy. She relinquishes her best friend, quite selfishly, for a futile personal ambition, and a journey for which she is woefully unprepared and tragically optimistic.

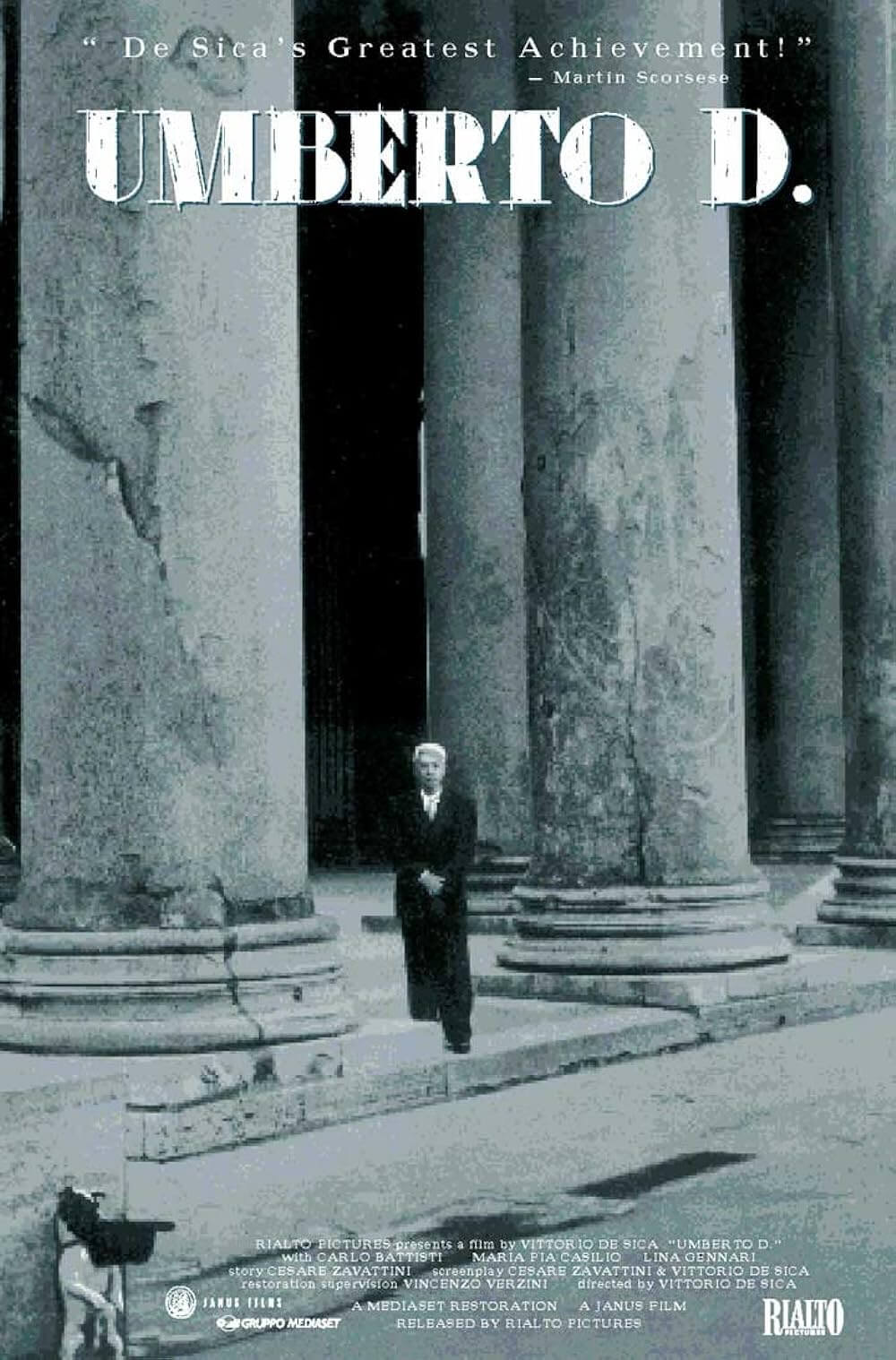

If there’s some mercy in Wendy and Lucy, it’s that Reichardt affords the viewer certainty about Lucy’s fate; she will be cared for and well-fed at her foster home. This is strangely satisfying, even as Wendy continues her course into an uncertain future. If nothing else, one could choose to believe that Reichardt’s previous film, Old Joy, which also features Reichardt’s Lucy in a major role, comes after Wendy and Lucy. Perhaps its yuppie liberal protagonist Mark has adopted Lucy from the foster home where Wendy left her, and the dog’s carefree weekend getaway in Oregon’s forests in that film represents her new life. Reichardt, who along with Raymond watched a lot of Italian Neorealism in preparation for Wendy and Lucy, delivers a modern-day version of Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D. (1952), about a destitute pensioner that considers suicide, except he cannot find a home for his dog Flike, so he resolves to stay alive and face poverty with Flike at his side. Contrarily, Wendy bends to Andy’s cruel remark: “If you can’t afford dog food then you shouldn’t have a dog.” Yes, both Reichardt and De Sica’s films condemn an indifferent society that does not care for those in need, whether they are elderly or poor, though Wendy and Lucy is far less fanciful or blindly hopeful than De Sica’s film. It underscores how there are systems in place to ensure stray dogs have a place at night to keep them warm and fed, whereas we have no widespread institutions for humans in the same condition. Wendy and Lucy may contain all the elements of a social drama, but its beauty resides in Reichardt’s masterful control of tone and tempo, Williams’ muted emotions, and our lasting gratitude that the story, mercifully, finds a safe place for Lucy, even if the same cannot be said for Wendy.

Bibliography:

Fusco, Katherine, and Nicole Seymour. Kelly Reichardt – Contemporary Film Directors. University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Hall, E. Dawn. ReFocus: The Films of Kelly Reichardt. Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Hornaday, Ann. “Director Kelly Reichardt on ‘Meek’s Cutoff’ and making movies her way.” The Washington Post. 18 May 2011. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/director-kelly-reichardt-on-meeks-cutoff-and-making-movies-her-way/2011/05/08/AFOl0K7G_story.html. Accessed 18 January 2020.

Van Sant, Gus, and Kelly Reichardt. “Kelly Reichardt.” BOMB, no. 105, 2008, pp. 76–81. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40428028. Accessed 15 Feb. 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review