We Need to Talk About Kevin

By Brian Eggert |

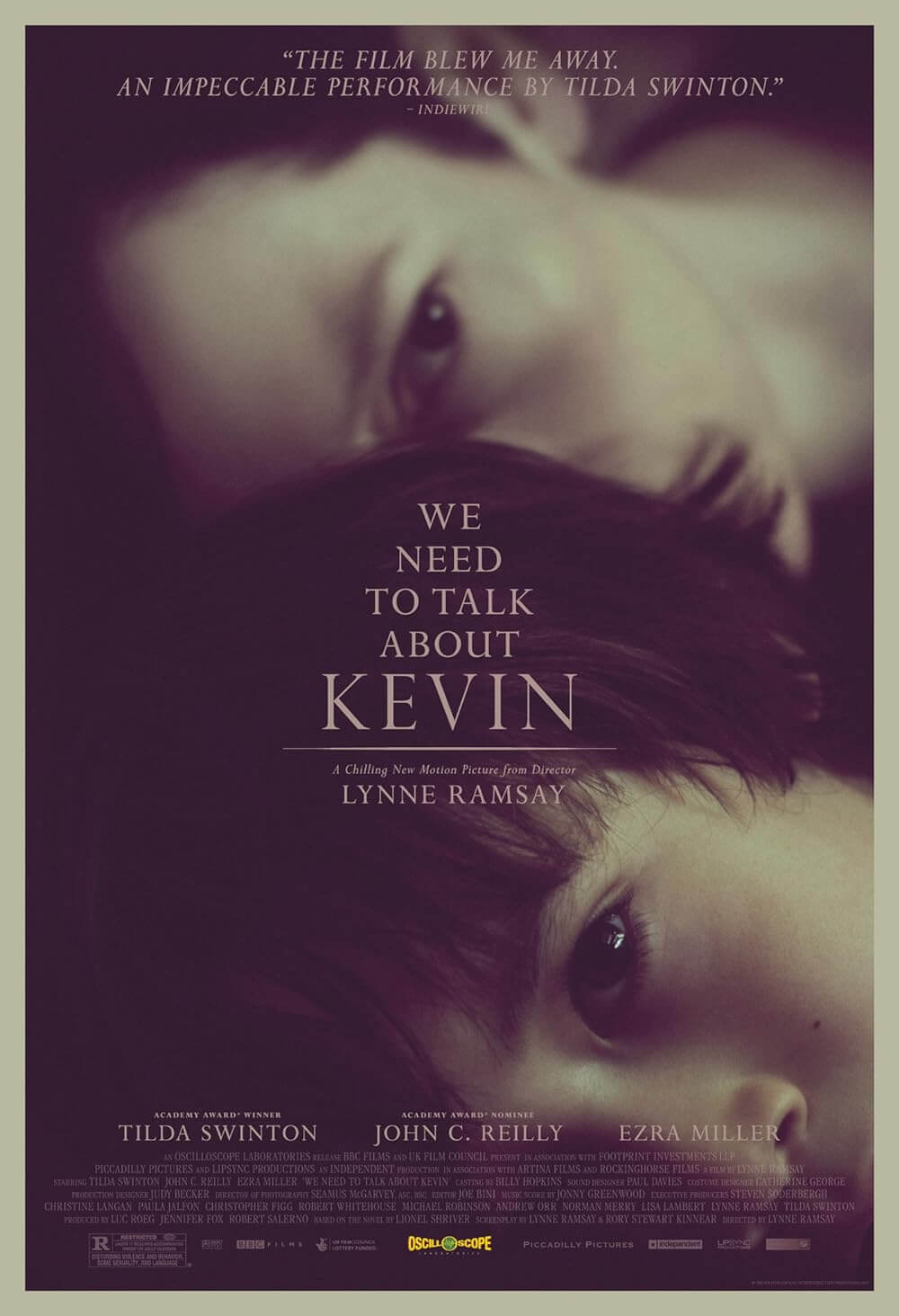

For We Need to Talk About Kevin, Lynne Ramsay draws from a downpour of misfortune to explore her frequent themes of sadness, uncertainty, and perceived guilt following a tragic death. Based on the novel by Lionel Shriver, Ramsay’s film uses evocative imagery and a non-linear narrative structure to create a stunningly observed series of disturbing scenes, which, as the viewer pieces them together, become so filled with dread that we squirm with unease long after the film has ended. The film debuted at 2011’s Cannes Film Festival, and aside from garnering star Tilda Swinton with a much-deserved Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress, it went largely unnoticed even in arthouse crowds. This British-American production is not a crowd-pleaser or a film that people will enjoy seeing; however, its powerful effect on its audience is unquestionable and calls for viewers who recognize that sometimes cinema should make us feel uncomfortable.

Swinton plays Eva, who has a child named Kevin with her husband Franklin (John C. Reilly). Since Kevin was a toddler, Eva has suspected he’s a sociopath, although he only seems to reveal that part of himself to her, never to his father. One day in his mid-teens, Kevin cordons off his high school gym and kills several of his classmates with a bow and arrows. Although we do not learn of this unmotivated spree until later, the film’s fragmented story bounces back and forth between Eva’s life before and after the incident, giving us little hints of the massacre along the way. Before, Eva struggles with her pubescent child (played by Jasper Newell), who seems to retaliate because she shows bitterness over how the boy has stolen her youth and freedom. Later, the teenaged Kevin (now played by Ezra Miller), becomes a narcissistic monster whose sadistic, cleverly disguised attacks advance from cruel to atrocious.

But is Eva’s lack of parental know-how or finesse with Kevin to blame for his behavior? Flashing forward to after Kevin’s attack, Eva’s life is in shambles. Hated by locals as the mother of a killer, her house is vandalized with buckets of crimson paint, just one of the film’s many uses of the color red. A beautiful sequence early in the film shows Eva participating in the tomato-smashing festival La Tomatina, wholly carefree for the only time in the film, or perhaps it just seems that way because the very next scene comes in the immediate aftermath of her son’s rampage. She’s drenched with a tireless feeling of responsibility for what happened. Whether or not she should blame herself becomes a question the viewer must answer. Given the sickening degree of Kevin’s behavior, one finds it difficult to find Eva culpable, even if she’d never win a “Mother of the Year” award. Then again, the film dances around what happened in court; we see Eva leaving the courthouse with a crowd of people wanting to tear her apart. What did she say in there? Did she apologize for her son and needlessly put the responsibility upon herself as the bad parent of a sick child? I think she did.

Despite the familiar “demon seed” story, if presented in a chronological order, the film’s individual scenes would not amount to something like Orphan or The Omen or any number of thrillers about a maniacal child-turned-psycho. Ramsay’s artful touches and intimate close-ups lend watchful moments a penetrative and grim mood, each more intent on creating the film’s lasting sense of apprehension beyond just horror chills. Her film is best aligned with Joshua, that underseen gem from 2007 starring Sam Rockwell and Vera Farmiga. Both pictures examine families whose parents resent the newborn child, and an intuitive child who manipulates both parents until they fall apart. But even that film feels organized without the dramatic intentions of We Need to Talk About Kevin, in which Ramsay delves into the psychology of her unreliable narrator by using striking visual imagery to propel Eva’s sense of justified dread and paranoia.

Swinton disappears into Eva in yet another incredible performance of many from this actress. We sympathize with her because Kevin manipulates her through her maternal weaknesses, and we understand her because we’ve all experienced similar (although decidedly less aggressive) frustrations with children. Swinton captivates and demands our attention, while newcomers Miller and Newell offer significantly well-rounded and creepy portrayals. Reilly’s performance brings the actor back to his indie roots and proves that, when he’s not Dr. Steve Brule, he’s actually a legitimate screen presence. But the real performance belongs to Ramsay and her close observations of these people, their interactions, and their mysterious internal makeup. Making only one other film (Morvern Callar, 2002) since her astounding 1999 debut Ratchcatcher, Ramsay may not have a prolific career, but her personal imprints are undeniable on We Need to Talk About Kevin. Perhaps a cautionary tale for modern parents who seem to openly resent their children for stealing away their youth, or perhaps a warning to parents that the period where youth is innocent becomes shorter and shorter as generations pass, this fascinating and haunting film confronts and disturbs, but no matter how you react you will not be able to look away.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review