We Live in Time

By Brian Eggert |

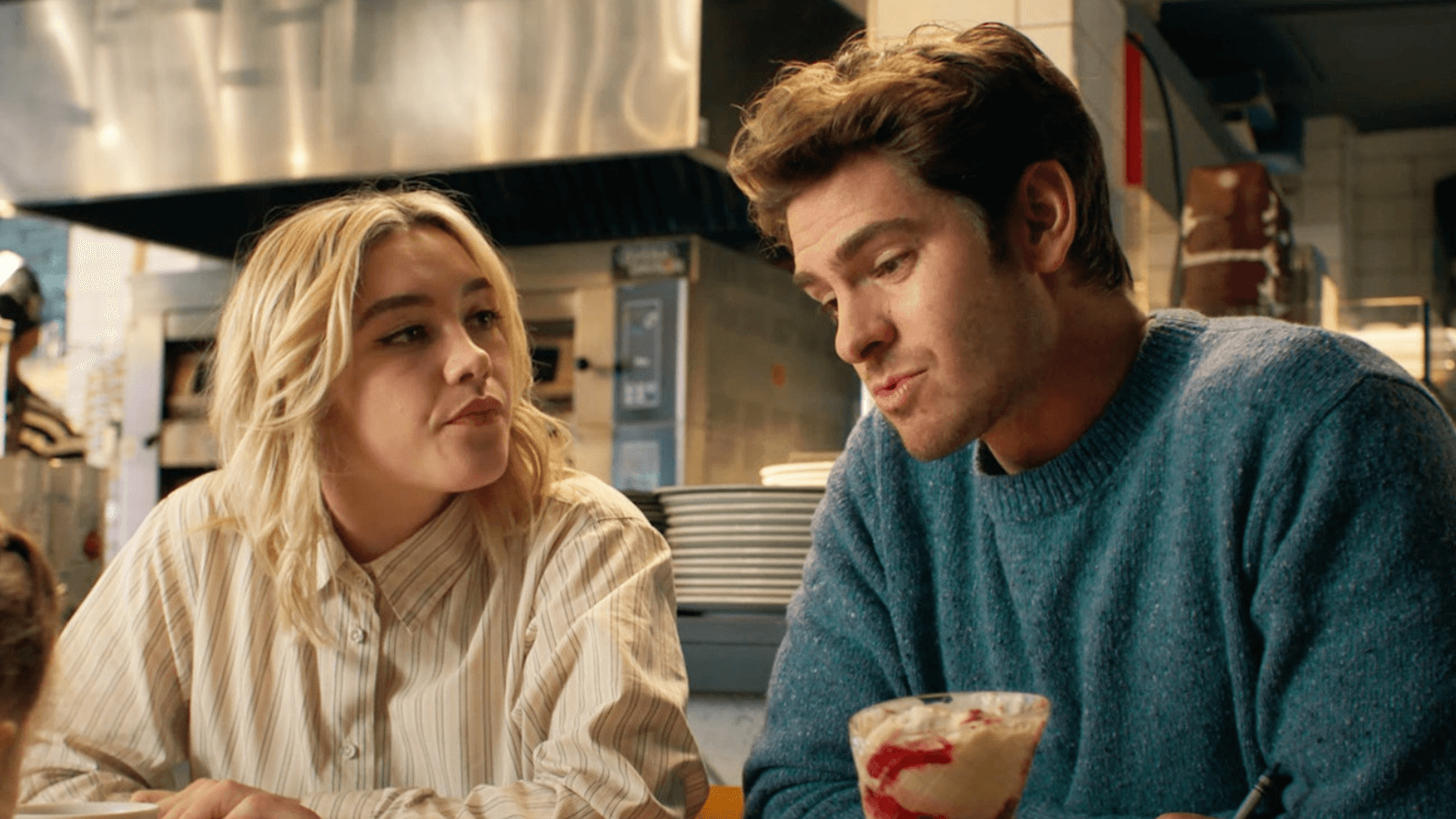

In the first few minutes of We Live in Time, writer-director John Crowley introduces us to Almut, played by Florence Pugh, a chef who lives in the English countryside in one of those spacious, modern-yet-pastoral homes with lush gardens and perfect lighting—the kind of abode that only exists in movies or belongs to the super-rich. After a jog, she prepares her partner, Tobias, a charming Andrew Garfield, a “Douglas fir parfait” for breakfast, waking him up with affection and smiles. Then Crowley cuts to Almut pregnant, sometime later or possibly before—we cannot be sure—with Tobias applying his knack for mathematical figures to the volume of her vaginal fluids and the timing of her contractions. Then the film shifts to another episode from their lives, this one with Almut receiving a cancer diagnosis, not her first, and saying she doesn’t want to go through that fight again. She would rather have “six amazing months than twelve shitty ones.” The chronology of these events proves intentionally unclear early in the film, with Crowley and editor Justine Wright cutting freely back and forth through time. Gradually, a picture forms. But given this early glimpse of love, parenthood, and more than one battle with cancer, it’s enough to prepare the audience: We’re in for it.

Pugh and Garfield have boundless chemistry in what, in another filmmaker’s hands, might be an insufferably schmaltzy narrative. Out of context, several chapters in Almut and Tobias’ life together might be dramatic clichés seen countless times in terminal illness dramas and romantic comedies. However, Crowley’s work is a testament to the power of editing and narrative structure to turn a conventional story into something that moves and often surprises you. Curiously, We Live in Time reminded me most of Strange Darling, a serial killer thriller from earlier this year that would have been a predictable bore if not for its innovative arrangement of events to keep the viewer’s attention. Films such as these, or those of early Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan, often engage in a gamesmanship that requires the viewer to process narrative information through the constant assembling of a puzzle. With each new piece, your mind attempts to situate the moment in relation to the others that immediately preceded it in the film. Only by the end does the puzzle come together.

Recounting the story for you, dear reader, will probably do you a disservice. Any attempt to set the stage might reveal too much, since our brains typically want to start at the beginning and expand from there. Suffice it to say, Pugh and Garfield meet, fall in love, have a child, and grapple with the former’s health complications. She’s an award-winning chef who runs an Anglo-Bavarian restaurant—a concept that intrigues, though the only glimpse of her cuisine is a single bite of a micro-sausage (still, this film is a foodie’s dream). Filled with self-assuredness, she is talented in ways not immediately obvious, beautiful, generous, yet independent and driven to lead a full life. Her impossibly perfect existence is only marred by her Stage 3 ovarian cancer, which registers as tragic in the way some romance novels and Hallmark Channel movies are. As for Garfield, he’s just as endearing, with a wounded and fastidious energy that makes him sympathetic and cute. His vulnerability can be aching. Charting the health of their relationship on the conflict meter, they never get above yellow (or a six, depending on which scale you use). Their biggest dust-ups involve whether or not she wants to have kids or, much later, an incident where they forget to pick up their child from school.

Crowley, whose last feature film, Brooklyn (2015), was a wonder, once again demonstrates his understanding of how small details and understated gestures can go a long way to flesh out characters. It helps that his two leads have a genuine magnetism, far removed from the wooden relationship weepies often found in Nicholas Sparks adaptations. Tobias enjoys eating cookies in the bathtub. Almut has a particular way of cracking eggs that involves three bowls, both efficient and inefficient in a quirkily admirable way. Tears almost came to my eyes watching Tobias eat the first bite of food she prepares for him (the aforementioned mini-sausage); he seems to fall in love at that moment. Similarly, consider the first time their characters have sex. She has invited him to her restaurant and, after discovering that he’s all but divorced, they go back to her place. They make love, at once like it’s their first time and as though they’ve been with each other countless times before this. That’s true of a lot of We Live in Time, suggesting both a sense of discovery for the viewer but also a feeling that everything we see has happened before and will happen again. There’s a familiarity and inevitability to it. “Time is a flat circle,” said a character in HBO’s otherwise unrelated True Detective, a reference to Nietzsche’s theory of eternal recurrence.

Crowley, whose last feature film, Brooklyn (2015), was a wonder, once again demonstrates his understanding of how small details and understated gestures can go a long way to flesh out characters. It helps that his two leads have a genuine magnetism, far removed from the wooden relationship weepies often found in Nicholas Sparks adaptations. Tobias enjoys eating cookies in the bathtub. Almut has a particular way of cracking eggs that involves three bowls, both efficient and inefficient in a quirkily admirable way. Tears almost came to my eyes watching Tobias eat the first bite of food she prepares for him (the aforementioned mini-sausage); he seems to fall in love at that moment. Similarly, consider the first time their characters have sex. She has invited him to her restaurant and, after discovering that he’s all but divorced, they go back to her place. They make love, at once like it’s their first time and as though they’ve been with each other countless times before this. That’s true of a lot of We Live in Time, suggesting both a sense of discovery for the viewer but also a feeling that everything we see has happened before and will happen again. There’s a familiarity and inevitability to it. “Time is a flat circle,” said a character in HBO’s otherwise unrelated True Detective, a reference to Nietzsche’s theory of eternal recurrence.

Moreover, it’s a small miracle that the viewer hardly notices Wright’s cutting. Apart from a few pointed examples, particularly near the film’s increasingly dramatic last third, where the cut becomes a device to present a sharp visual contrast to the scene before—now she’s giving birth, now she’s sick, now she’s setting everything else aside to compete in “culinary Olympics” for the Bocuse d’Or, etc.—the cut remains invisible. Instead of form or titles that denote the leaps in time, the narrative supplies visual or contextual clues, requiring the viewer to assess the scene and place the puzzle piece at the start of each new sequence—a process that becomes wholly unconscious after the film’s first minutes. Much like in Brooklyn, Crowley’s visual treatment doesn’t stray from the clean cinematography by Stuart Bentley, the cozy production design by Alice Normington, and the comfortable, stylish, but unflashy costumes by Liza Bracey. All of that textured detail recedes, allowing the stars to shine. The same is true of Bryce Dessner’s music, an entirely complementary score that Crowley refreshingly resists drowning out with a catchy soundtrack that might provide an all-too-easy direct line to the viewer’s emotions.

A cynical review of We Live in Time might dwell on the story’s familiarity after it’s all been laid out in your mind. The sheer number of Big Dramatic Moments contained here feels like they have been shot for the trailer—and in another universe, We Live in Time would be a 104-minute trailer for a years-long series about this relationship. As ever, the distributor at A24 has nailed the marketing, ensuring its audience is primed for an emotional rollercoaster with a sampling of these moments (yet, there’s a disappointing lack of the first poster’s yellow carousel horse creeping into the scene). And sure enough, there won’t be a dry eye in the house, save for those few who cannot get on its wavelength. Still, the film’s emotional immediacy is unwavering throughout, driven by well-rounded performances that let us both bask in the charisma of these stars and fall in love with their characters—a quality that allows us to focus on the experiential rather than the puzzlework. The structure underscores how life is a series of small, precious moments, and savoring each gives them meaning. Each scene feels unique and special, like tracks from the Greatest Hits album of Almut and Tobias’ life. Some viewers may balk at such compilations, preferring deeper cuts from lesser-known albums. But sometimes, one just wants those standards that, despite being corny and overplayed, still manage to keep our toes tapping.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review