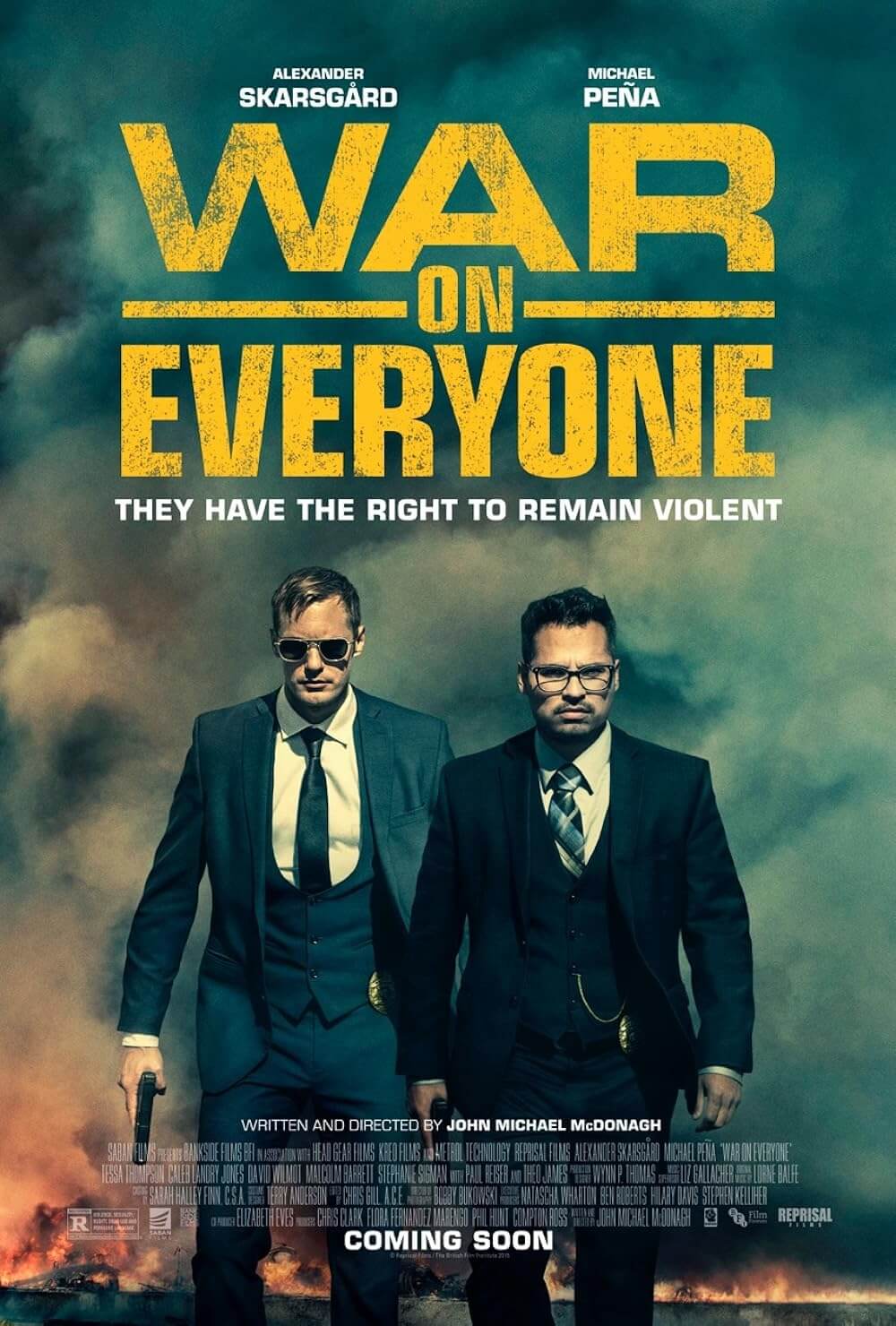

War on Everyone

By Brian Eggert |

When a buddy comedy about nihilistic, gleefully depraved detectives arrives after a year saturated with social unrest over a staggering number of unjust police shootings, audiences and critics alike are bound to recoil. But there’s something ingenious and wonderfully anarchic about John Michael McDonagh’s War on Everyone. It’s the kind of post-Tarantino film in which the two cops at the center show up to a bloody murder scene chowing on hamburgers in one hand, their pistols in the other. But it’s also the kind of film in which characters debate philosophers like Simone de Beauvoir, casually reference Andre Breton, and read books like John Hersey’s The Algiers Motel Incident, a true crime story about a racially charged police shooting from 1968. In other words, McDonagh has made a self-aware, thinking person’s dirty cop comedy.

Of course, War on Everyone may represent a general “F-you” from the perspective of the current zeitgeist and attitude about corruption and police killings, making it the wrong film for the wrong time. Nevertheless, McDonagh’s postmodern riff contains a highbrow sensibility that will make it last until people are ready to appreciate its caustic nature. Set in Albuquerque, the film follows Terry Monroe (Alexander Skarsgård) and his partner, Bob Bolaño (Michael Peña), as they drive around in Terry’s retro muscle car, waxing philosophical and running down thugs for a snort of stolen cocaine or a coerced bribe. For the duration of the film, Terry and Bob walk the line between affected conversations about the meaninglessness of existence and the lowbrow mockery of various races, disabilities, and sexual preferences. Neither of them seems concerned about the prospect of losing their jobs over their behavior. Bob doesn’t mind another set of assault charges, while Terry celebrates his freedom to shoot anyone he wants with no real consequences.

But McDonagh acknowledges that Terry and Bob are outdated tropes, not only with their affection for three-piece suits but through his formal choices. Consider cinematographer Bobby Bukowski’s canted framing of most scenes to reflect this off-kilter world. Likewise, Wynn Thomas’ production design evokes the rusted colors of a 1970s cop movie, while Lorne Balfe’s horn-heavy score supports that notion. Add to that the soundtrack with plenty of songs by Terry’s favorite musician Glen Campbell, and there’s a lingering sense of the past throughout War on Everyone. McDonagh even embraces the old formula of a shouting police chief; however, Paul Reiser takes on the chief role and delivers some of the film’s best laughs. “This is the police department,” says Reiser concededly. “We’re surrounded by big fat racist pigs.” And watch as Terry and Bob try to keep a straight face during their chief’s lecture against police corruption—it’s downright hilarious.

Much like last year’s The Nice Guys, another ’70s riff on buddy cop comedies, the plot of War on Everyone is a tangled web. After Terry steals away his informant’s girlfriend Jackie (Tessa Thompson), the informant dies during a botched racetrack robbery. One million in cash is missing from the robbery, and the detectives expect a sizeable cut. Unfortunately, Reggie X (Malcolm Barrett), another informant-turned-robber, has skipped town to Iceland with the money. But Terry and Bob track him down only to learn their money is with sadistic British crimelord Lord James Mangan (Theo James), a businessman who moonlights as a strip club owner and child pornographer. Alongside Mangan is weirdo henchman Birdwell (Caleb Landry Jones), who responds with violence after Jackie turns down his proposition to appear in a porno. Though various twists and turns arise along the way and the film ends with a shootout, the story feels less significant than the characters and their complex worldviews.

Much like last year’s The Nice Guys, another ’70s riff on buddy cop comedies, the plot of War on Everyone is a tangled web. After Terry steals away his informant’s girlfriend Jackie (Tessa Thompson), the informant dies during a botched racetrack robbery. One million in cash is missing from the robbery, and the detectives expect a sizeable cut. Unfortunately, Reggie X (Malcolm Barrett), another informant-turned-robber, has skipped town to Iceland with the money. But Terry and Bob track him down only to learn their money is with sadistic British crimelord Lord James Mangan (Theo James), a businessman who moonlights as a strip club owner and child pornographer. Alongside Mangan is weirdo henchman Birdwell (Caleb Landry Jones), who responds with violence after Jackie turns down his proposition to appear in a porno. Though various twists and turns arise along the way and the film ends with a shootout, the story feels less significant than the characters and their complex worldviews.

Peña often serves the role of a comic relief supporting player (see The Martian or Ant-Man), and he rarely appears as a lead. Here, he splits those duties with Skarsgård and demonstrates his capacity for leading man status. In scenes with his family, he has a deadpan sarcasm and wit that proves scathing, but he’s also endearing once you understand the eccentric rhythms of his marriage to his equally iconoclastic wife (Stephanie Sigman). He also proves he’s capable of complex line deliveries loaded with intellect, humor, insults, and irony in the same sentence. Meanwhile, Skarsgård, the towering actor from True Blood and The Legend of Tarzan, embodies a role that seems to combine the existentialism of Max von Sydow in The Seventh Seal (1957) and the physical transformation of Nicolas Cage in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009). Indeed, Skarsgård plays an admitted alcoholic-and-proud-of-it who makes allusions to his traumatic childhood and nothing-matters attitude, which seems to have left his posture hunched and warped.

McDonagh’s War on Everyone never dwells on violence or mindlessness, despite being a violent and bloody film. Much like Tarantino, or McDonagh’s brother Martin (responsible for In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths), the filmmaker settles in the conversations between his characters, as well as their philosophical and inward natures—even in the face of their reckless lashing-out. Terry and Bob’s behavior leads to violence, but the shootouts and severe beatings are mere punctuations resulting from more compelling, thoughtful, and humorous moments between them. This was also the case of McDonagh’s earlier films starring Brendan Gleeson, The Guard (2011) and Calvary (2014). Above all, War on Everyone proves relevant and well aware of its rancid portrayal of amorality, leaving it to question how exaggerated characters such as this could ever get themselves a badge and gun. Ultimately, though, McDonagh finds Terry and Bob in a place where even they admit they shouldn’t be cops, and suddenly the film does not seem so inappropriate for today as we initially thought.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review