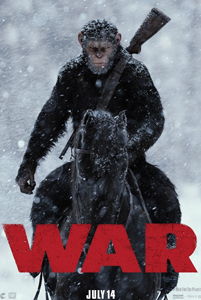

War for the Planet of the Apes

By Brian Eggert |

The second ape-themed blockbuster in 2017 to draw from Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), War for the Planet of the Apes marks the third entry in the revisionist franchise, and potentially the final sequel before yet another remake of The Planet of the Apes (1968). Setting aside how the film uses the same Vietnam-inspired thrust as Kong: Skull Island, Twentieth Century Fox’s reboot series boasts impressive, photo-real special FX and CG-animation that bring its simian characters to vivid life. Director Matt Reeves oversees a gorgeous-looking production—a capable and often wonderfully realized use of technology. It places intricately realized ape characters into situations that highlight both the sheer spectacle of their creation and their humanistic qualities, therein deepening characters and drawing the viewer’s sympathies to an unlikely side in the human-simian war. But the script by Mark Bomback and Reeves follows the comparatively subtle Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011) and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (2014) with a heavy-handed approach, relying on biblical and cinematic references to embolden its epic quality more than the inter-species relationships at the film’s center.

Beginning several years after Dawn, the film’s opening titles establish an ongoing conflict between the heroic ape leader, Caesar (Andy Serkis, once again delivering an incredible motion-capture performance), and the militant human leader, known as “the Colonel” (Woody Harrelson). With the human race dwindling fast, the Colonel targets Caesar, killing his family in a botched assassination attempt. Caesar decides to take revenge, sending the rest of the apes to a sanctuary beyond the snowy mountains, while he sets out toward the Colonel’s compound, accompanied only by his loyal bodyguard Rocket (Terry Notary), the wise orangutan Maurice (Karin Konoval), and the gorilla Luca (Michael Adamthwaite). After rescuing a human girl, Nova (Amiah Miller), whose father Caesar killed, their group heads to the compound. In the interim, however, the Colonel has captured Caesar’s entire ape clan and forced them into subjugation to erect a wall (sound familiar?) designed to protect his compound from other, warring humans. When he captures Caesar, the oft-monologuing Colonel attempts to break our hero’s resolve, clinging to the last bastion of humankind that, he admits, is doomed either way.

Every major story setpiece in the film has a direct corollary to an alternate text of some kind, to the extent that watching War for the Planet of the Apes becomes an act of reference identification, distractingly so. The narrative’s theme of a posse heading out on horseback to avenge the hero’s fallen family, while he just barely avoids succumbing to his own hatred, pulls from The Searchers (1956) and John Wayne’s racism-fuelled mission to recover his niece from Comanches. As suggested, the arrival at the hellish human compound and Caesar’s interactions with the Colonel resemble Apocalypse Now—there’s even graffiti reading “Ape-Pocalypse Now” scrolled on a wall by some pun-loving human survivors. Harrelson plays the role as if combining Marlon Brando’s Col. Kurtz with Ralph Fiennes’ Amon Göth from Schindler’s List (1993), as he shaves his scalp with a straight razor and, from his command tower, looks down at his loyal soldiers and ape prisoners. The dynamic that informs the wall-building scenes, where the taskmasters must negotiate with (and torture) the prisoners’ leader to get work done, derives from The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957). And behind bars, the apes plot a way out to a playful theme by composer Michael Giacchino, reminiscent of The Great Escape (1963).

Using influences galore, the filmmakers adopt an appropriately epic-sized production, but unlike the film’s two predecessors, the result feels like an extended pastiche. Reeves and Bomback also evoke iconography—more than I can acknowledge in this review—out of desperation to establish allegorical significance to Caesar. The religious subtext cannot go unnoticed (the screenwriters won’t allow it to). Whether his fellow apes ask “What would Caesar do?” in his absence or he leads his people across punishing terrain to the promised land, Caesar has been aligned with Jesus and Moses, complete with an uplifting finale into the clouds reminiscent of one in last year’s equally overwrought Hacksaw Ridge. None of these cinematic or religious references by themselves would be so offensive, except their culmination amounts to a paint-by-numbers storyline. Worse, the writers also define the characters with heavy-handedness, even when there’s no point of reference: Isn’t it convenient how Caesar, Nova, and the Colonel each have either lost a child or a parent, and how each of their dramatic arcs is defined by that loss?

Using influences galore, the filmmakers adopt an appropriately epic-sized production, but unlike the film’s two predecessors, the result feels like an extended pastiche. Reeves and Bomback also evoke iconography—more than I can acknowledge in this review—out of desperation to establish allegorical significance to Caesar. The religious subtext cannot go unnoticed (the screenwriters won’t allow it to). Whether his fellow apes ask “What would Caesar do?” in his absence or he leads his people across punishing terrain to the promised land, Caesar has been aligned with Jesus and Moses, complete with an uplifting finale into the clouds reminiscent of one in last year’s equally overwrought Hacksaw Ridge. None of these cinematic or religious references by themselves would be so offensive, except their culmination amounts to a paint-by-numbers storyline. Worse, the writers also define the characters with heavy-handedness, even when there’s no point of reference: Isn’t it convenient how Caesar, Nova, and the Colonel each have either lost a child or a parent, and how each of their dramatic arcs is defined by that loss?

Meanwhile, the screenplay’s attempts to attach importance to the proceedings have distracted its writers from smaller, albeit significant details. Consider how several emotional scenes feature the apes signing to one another. Reeves has blocked these shots for full dramatic effect, with Caesar facing the audience, looking distraught, while his back remains to whoever’s speaking in sign. Somehow, regardless of his back being turned, Caesar understands the nonverbal signs. Is there a mirror in front of him? Is he reading the same subtitles that we are? Elsewhere, the screenplay has broken its own rules from Rise and Dawn. Early in the film, Caesar’s group comes across a lone ape who can speak. He calls himself “Bad Ape” and talks with the dopey dude-voice of Steve Zahn, providing a goofy comic relief character. The problem is, Bad Ape claims he was never exposed to the virus that made Caesar and his followers ultra-intelligent; the film suggests he just evolved the ability to speak out of necessity. Somehow, this was the second most unbelievable development in a film that features the complete destruction of the human race by talking apes. The most unbelievable development is the laughable avalanche solution in the finale.

Although I thoroughly enjoyed Rise and Dawn, the third film in the “Caesar trilogy” disappoints by constructing its narrative almost entirely of references, well-treaded formulas, and allegories abound (American slavery and racial tensions have unmistakable relevance here as well). Every plot twist and outcome can be anticipated far in advance, while the characters grow in unsurprising ways thanks to the writers’ over-reliance on familiar story structures. This is all the more disappointing because Reeves has made a formally impressive film. The grayed-out, wintry lensing by Michael Seresin and coherent editing by William Hoy and Stan Salfas deliver a stable visual experience, while Giacchino’s music carries the picture along. And the viewer will undoubtedly spend a large portion of this two-hour-and-twenty-minute feature examining how amazingly detailed the CG ape characters look, making the otherwise monumental advancements in the first and second entries seem subpar by comparison. But War for the Planet of the Apes squanders its actors, FX, and formal presentation on a story that feels lazily compiled from other material, marking a bitter end for Caesar and this otherwise admirable trilogy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review