Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl

By Brian Eggert |

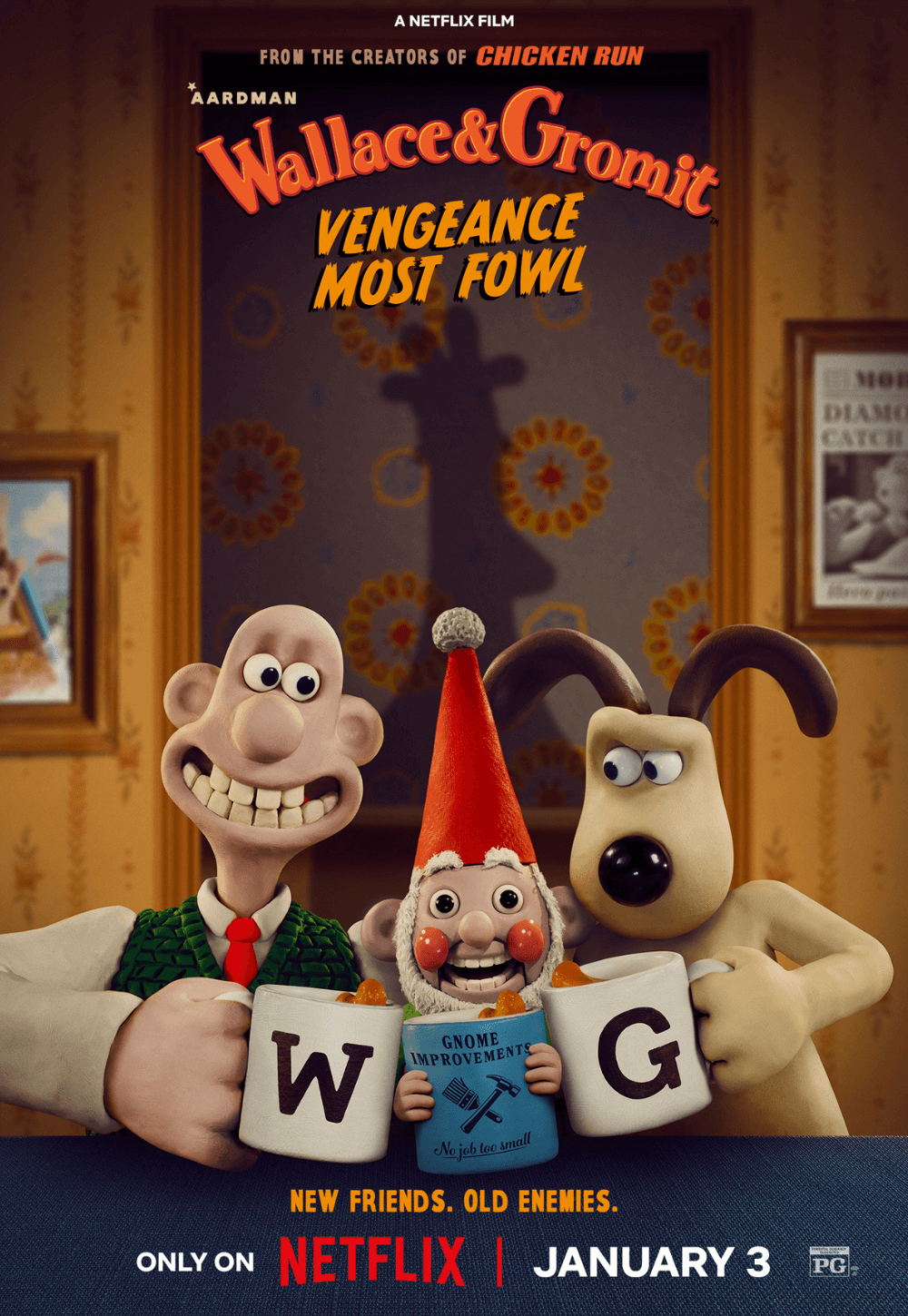

Nearly twenty years have passed since Wallace and Gromit appeared in theaters. The hapless, cheese-obsessed inventor, usually upstaged by his knowing beagle, Gromit, last appeared in 2005’s The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. Since then, Aardman Animations has cut ties with their distributor at DreamWorks after British claymation wizard Nick Park had endured enough notes from executives about making Chicken Run (2000) and other projects more suitable for US audiences. But part of what makes Wallace and Gromit special is that they’re unlike the usual Hollywood family entertainment, trimmed and readied for American eyes. Some of Aardman’s charm rests in its distinct Britishness, along with Park’s penchant for riotous sight gags worthy of Buster Keaton and no end of visual and aural puns. How fitting that the second feature-length outing for Wallace and Gromit, Vengeance Most Fowl, should be distributed by the BBC and Netflix, giving Park and the Aardman team the resources and freedom to create another idiosyncratic and memorable installment.

Fans of the series haven’t been inundated with new Wallace and Gromit adventures, despite The Curse of the Were-Rabbit becoming the first stop-motion film to earn the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, making the latest a welcome return. After Park’s 1989 debut short, A Grand Day Out, the characters appeared in other short films: The Wrong Trousers (1993), A Close Shave (1995), and A Matter of Loaf and Death (2008). Of course, Park has been building the Aardman portfolio with other claymation features (The Pirates!, 2012; Early Man, 2018) and dabbling in computer animation (Flushed Away, 2006). And even while the long-running Wallace and Gromit spinoff series, Shaun the Sheep, has become arguably more popular and prolific than the originals, the inhabitants of 62 West Wallaby Street in Wigan, Lancashire, England, haven’t lost their appeal or become overexposed.

Today, the absent-minded Wallace (voiced by Ben Whitehead), with his green sweater vest and brown slacks, and his eye-rolling best friend Gromit, hardly seem like cutting-edge characters. Yet, the story by Park and screenwriter Mark Burton includes germane themes about the dangers of technology at a time when debates about artificial intelligence run rampant through every industry. Sure enough, the story finds Wallace advancing from his usual Rube Goldbergian contraptions, which make the simplest tasks—getting out of bed, dressing, applying jam to toast—far more complicated than they need to be, to robotics. One day, when Gromit attempts to unwind with light gardening, Wallace introduces his latest invention: Norbot (voiced by Reece Shearsmith), an automaton garden gnome designed to help with household chores.

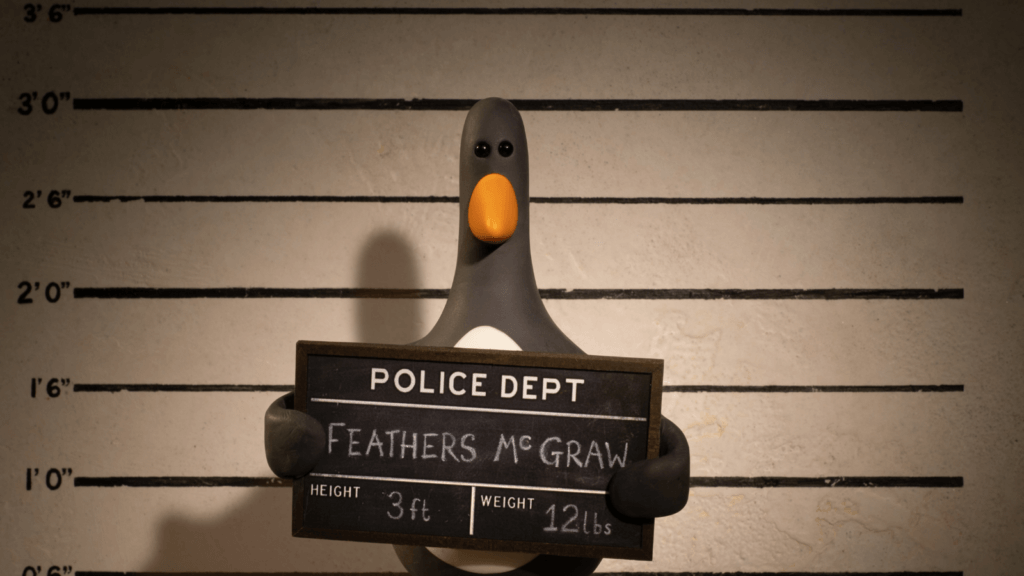

Norbot’s quick completion of lawn mowing and hedge trimming earns the attention of Wallace’s neighbors, even a local news segment with anchor Onya Doorstep (Diane Morgan). But for Gromit, the short robot’s zippy efficiency misses the point—sometimes, the time and care put into labor makes performing a task more rewarding. Worse, the news coverage captures the attention of Feathers McGraw, the steely penguin villain of The Wrong Trousers, who has since been locked away in the zoo after the protagonists thwarted his diamond heist. In a plot thread reminiscent of Cape Fear (1991), McGraw plots his revenge and uses the Norbot to facilitate another escape and heist. In turn, Chief Inspector Mackintosh (Peter Kay) follows his gut to pin the crime on Wallace, whereas the new Lieutenant PC Mukherjee (Lauren Patel) prefers facts and evidence.

Co-directed by Park and Merlin Crossingham, the nimble, 79-minute feature wastes not one minute of screentime, packing every frame with gnome puns and visual jokes. The most inspiring sequences involve Gromit and McGraw—voiceless characters who nonetheless command the viewer’s attention with their subtle, expressive action. McGraw is one of Park’s more inspired creations, turning the usually cute animal into a menacing figure with a hilariously piercing, dead-eyed stare. Many of the best jokes involve absurdly elaborate solutions when something simpler would suffice—a trend that underscores the film’s central theme. Besides Wallace’s inventions, note the sequence when McGraw builds an extended hand that reaches past the keys that would unlock his cell; instead, the criminal mastermind uses the device to hack into Wallace’s home.

As always with Park’s work, the animation looks superb, with only a hint of CGI augmentation here and there, usually to render believable-looking liquid, smoke, or fire effects. This comes in most handy during the extended chase sequence in the finale. The mild use of computers might also serve as a slight formal commentary embedded into Vengeance Most Fowl to support the narrative one—that modern technologies can be useful, if applied in moderation. The same logic applies to the hand-crafted quality of claymation, where occasionally, the animator’s fingerprints can be seen on the characters, leaving tangible evidence that enriches and humanizes the animation. By contrast, you lose something by allowing automation and artificial intelligence to run your life simply because the possibility exists. It’s a notion lovingly articulated with Wallace’s ability to build a robotic arm that can pat Gromit’s head, though his canine companion prefers it when Wallace shows affection himself.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review