Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

By Brian Eggert |

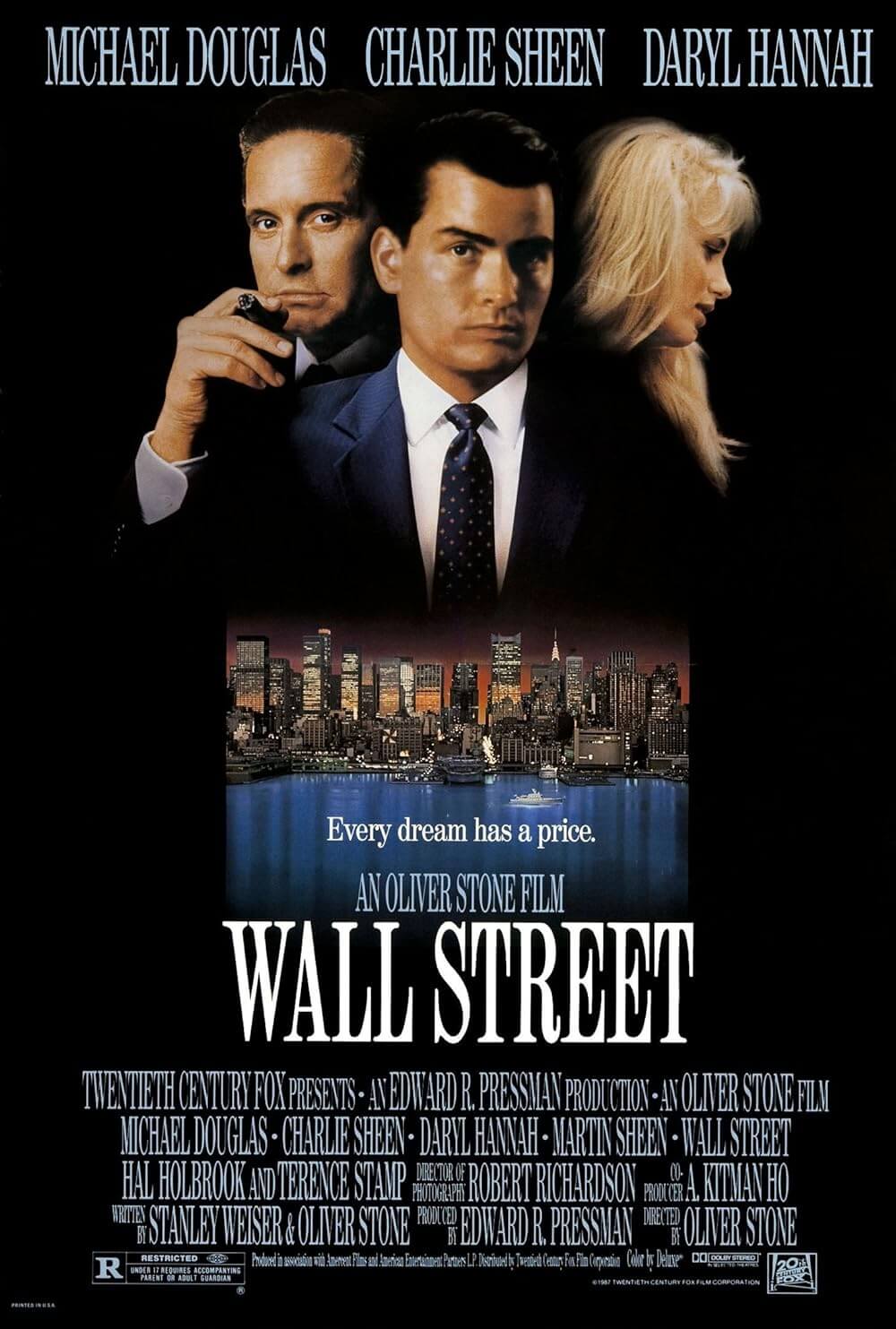

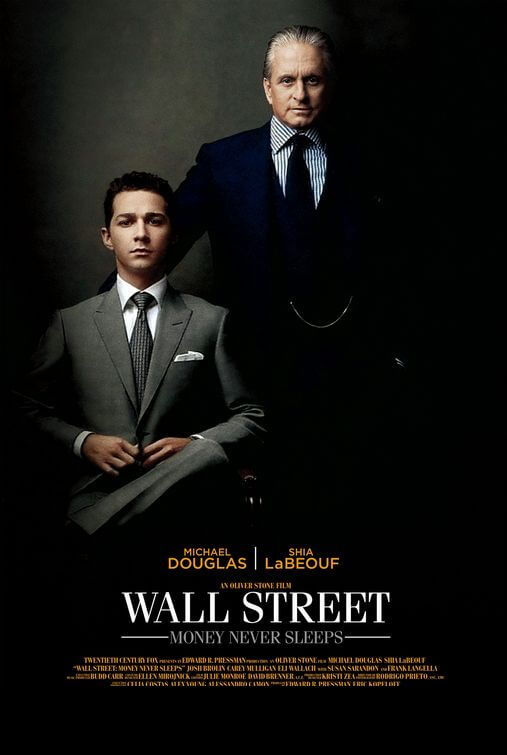

Oliver Stone didn’t have reason to make a sequel to his 1987 film Wall Street until 2008. By chance, the original opened the Friday before the Black Monday market crash, which no doubt sent audiences to revel in cinemas at Stone’s take on systematized greed. That film put a face to such villainy with Michael Douglas’ Oscar-winning portrayal of Gordon Gekko, the power broker who faced certain jail time for insider trading at the end of the original. The Gekko character has since become a model for financial sharks looking to take a bite out of the market, the ones who quote the character’s signature line “Greed is good” without a hint of irony. And since the 2008 market crash, it’s become apparent that there are greater villains in the financial industry than Gordon Gekko.

Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps sets sights on the orchestrators of today’s global financial crisis through a strong melodrama, recounting shameful government bailouts for seedy business plans. Allan Loeb and Stephen Schiff’s script opens in 2001, when Gekko is finally released from prison, handed his brick-sized Motorolla, and set into the world once again, this time humbled. In the interim between films, the character has served eight years of prison time, been divorced, given up his fortune, lost his son to a drug overdose, and his daughter Winnie (Carey Mulligan) now refuses to speak to him. Jump to 2008 when the majority of the film takes place. Gekko releases a best-selling book about the financial world that has him giving university lectures on how today’s students are of “the NINJA Generation: No Income, No Job, no Assets.” He appears to have developed a conscience in prison, citing today’s investment banking goons as the real criminals. But young broker Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf) mistakes Gekko’s signs of resurgence as being a born-again father and trusts the former insider with business advice in exchange for information on his estranged daughter, Jake’s fiancée.

When Jake’s aging boss Lewis Zabel (Frank Langella) commits suicide after being ousted by his fellow bankers for his firm’s unrecoverable debt, it leaves Jake without a mentor. Gekko fills that void on the periphery, while sleazy big-timer Bretton James (Josh Brolin) attempts to use Jake in his firm Churchill Schwartz (a thin cover of Goldman Sachs). James serves as a truly despicable villain that at once shows how the former Gordon Gekko wasn’t that bad, while today’s monsters of modern banking barely resemble human beings. Of course, Jake avoids telling Winnie how involved he is with both James and above all her father, risking everything to make a hundred-million-dollar deal. Yet the differences between LaBeouf’s Jake and Gekko’s original apprentice, Bud Fox (played by Charlie Sheen in the original), are many. Jake’s love for Winnie, his unwillingness to commit outright felonies, and his idealistic backing of a fusion-power company for a greener world make him a better hero than the easily corruptible and shallow Fox character.

Devotees to the original will notice that while the story structures between Stone’s two Wall Street films prove similar—in both, the unknowing apprentice becomes a puppet to his mentor, only to help orchestrate his mentor’s downfall. But there’s an emotional significance here that the first lacked. The central love story between Jake and Winnie adds an unexpected level of involvement for a viewer seeking merely another of Stone’s spirited takes on a popular issue. The tonal difference, one will notice, echoes in the music. The original featured lively but dramatically vacant electronic music from David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts album, which paired well with the flashing momentum of red digital ticker machines. Here, Byrne and Eno return, but with affecting songs from Everything That Happens Will Happen Today, a calmer, more expressive selection of music sets the tone for the viewer rather nicely. And just like his music selection, Stone makes his film motivated by passions and human foibles, despite the likelihood that young modern-day brokers will be quoting Gekko’s new line, “It’s not about the money. It’s about the game.”

Portraying what ultimately becomes ‘the softer side of Gordon Gekko’ has its downfalls, however, as Stone has always been his best when he’s angry. He was angry when he tackled a military dictatorship in Salvador; when he wept for “innocence lost” in Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July; when he depicted the end of American virtue with an assassination in JFK; when he attacked the media with Natural Born Killers. In recent years, Stone’s anger has calmed, leaving us with unfortunate films like Alexander and World Trade Center. And within the first half of Money Never Sleeps, we see that angry Stone once more jabbing at the greed mongers for turning the country (and indeed the world) on its fiscal belly for their own taste of more-more-more. There’s talk of investment trends ranging from the internet to solar power as “bubbles”, which become a reoccurring theme throughout; there’s a comparison of James to Saturn from the Goya painting Saturn Devouring His Children; and there are back-room meetings to discuss how a bailout can make everyone involved even richer. But in the second half, Stone gets sentimental by offering an unlikely happy ending that instead could have dealt a harder set of life lessons. But romantics in the audience may appreciate the improbable twist of Gekko becoming an anti-hero, even if it doesn’t really stay true to the character.

In some respects, Money Never Sleeps is a superior film to the 1987 original. The first film suffered from some second-rate acting by way of Sheen (who appears in cameo here) and Daryl Hannah. Those errors are corrected with LaBeouf and Mulligan. Winnie has Mulligan’s face of innocence to make up for her thin characterization, making her instantly sympathetic while enclosed by the film’s surrounding gang of Wall Street wolves. In general, LaBeouf makes excellent use of his fast-talking persona when he’s being chased by giant robots or swinging from trees with monkeys, as his energy makes bad dialogue better; but with Leob and Schiff’s superb dialogue, LaBeouf shows how truly talented he is. Supporting players like Langella, Susan Sarandon, the sharp-as-ever Eli Wallach, and especially Brolin (whose embodiment of George W. Bush in Stone’s W. was grossly overlooked at the 2009 Oscars) each gives strong performances as well.

Once again in a supporting role to a younger actor (but stealing the film) is Douglas. Earlier this year he starred in Solitary Man, a dramedy that could have been a sequel to Wall Street where Gekko hit rock bottom. It was an affecting portrait of a man who realizes that wheeling and dealing have taken him nowhere. Gekko has that same epiphany in Money Never Sleeps, and Douglas slyly adds another layer to his most enduring screen character—a layer that comes unexpectedly, albeit welcome. Though his reprisal of Gekko may not earn him another Oscar nomination and win, it’s Douglas’ best performance in a decade, since Traffic and Wonder Boys, both in 2000.

This is also Stone’s best film in more than a decade (which isn’t saying much). Manic arrays of financial statistics, bravado editing, and split-screen sequences by David Brenner and Julie Monroe, fluid camerawork by Rodrigo Prieto, and a gorgeous production design by Kristi Zeal lend the picture a visual ingenuity not evident in Stone’s work since Any Given Sunday. Stone succeeds in making Money Never Sleeps part social commentary and part melodrama for a curious mix that leaves the viewer extremely satisfied. Had a sequel to Wall Street been made earlier, sometime within the 1990s, without question it wouldn’t have been as germane. Had it been later, well, there’s no telling what surprises our economy has in store that could be satirized by the radical director. Waiting as long as he did for something like the 2008 crash provides Stone with his needed backdrop, giving audiences exactly what a sequel to his American classic needs. Relevancy.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review