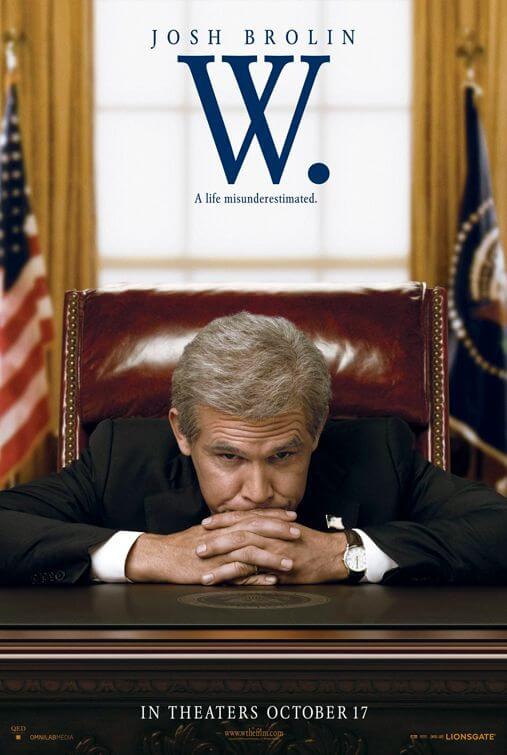

W.

By Brian Eggert |

Oliver Stone’s George W. Bush biopic, plainly titled W., views its topic with surprising empathy—in any case, more than anticipated from the radical director often associated with conspiracy theories, anti-war themes, and harsh political criticism. Rather than make grand censures, Stone humanizes “Dub-ya” through an astounding and unexpected portrayal by Josh Brolin (No Country for Old Men), examining the Commander-in-Chief from a psychological perspective versus overtly dwelling on the blunders of his presidency. Although, the two are undoubtedly related.

Brolin embodies his role completely, allowing the audience to forget there’s an actor toiling to perfect every mannerism and speech inflection. From body language to the signature “heh-heh” snicker, Brolin simply is George W. Bush. Capturing Bush’s external attributes, Brolin also provides an understanding of a role that has inspired many lampooning impersonations. Easily the best work of his career, it goes beyond a caricature and heads straight into the realm of greatness, and come awards season, Brolin should be remembered for his uncanny performance.

Brolin’s accomplishment is not alone; the cast is littered with fine acting. Take James Cromwell, who, towering over his costars, lends dignity to George H.W. Bush (aka “Poppy”). Richard Dreyfuss plays “Vice” Dick Cheney, representing him with callous reserve without turning him into a villain. Jeffrey Wright evokes a sensitive and logical force in the room as Colin Powell. Scott Glenn’s Donald Rumsfeld has a mad wit. Toby Jones makes a boyish yet conniving Karl Rove. Ellen Burstyn’s Barbara Bush is ferocious. And Elizabeth Banks is placed in the background as Laura Bush. All of them give natural performances, and the actors disappear into their respective roles. The sole exception is Thandie Newton’s Condoleezza Rice, which seems more like a sketch-comedy parody comparable to Tina Fey’s recent Sarah Palin impersonation.

The story, by Wall Street co-writer Stanley Weiser, is straightforward, beset with daddy issues and lifelong jealousy: Poppy doesn’t give Junior the attention he craves. Junior grows up spoiled, his father always pulling strings for him. Living in the shadow of his family’s successes, Junior struggles to find his niche and, after kicking the drink, becomes a born-again Christian. (All Presidential staff meetings end with a prayer, calling to mind not only how this goes against the Constitution’s separation of church and state edicts, but also Bill Maher’s apt statements about the Administration’s religious fervor in his recent documentary Religulous.) Junior resents that Poppy doesn’t place as much interest in him as he does the other son, Jeb. And watching as Poppy fails in “finishing the job” during The Gulf War, Junior seeks to outdo his father, viewing Iraq as his chance to live up to the family name.

By refusing to show the events surrounding 9/11, and instead discussing the attacks in conversations after the fact, the film better penetrates the emotional, oil-hungry, and vengeance-seeking decision to preemptively strike Iraq without proof of weapons of mass destruction—outlining this hasty action as the defining moment, and defining mistake, of Bush’s terms in office. In a press junket scene, one reporter asks Bush to look back at his first term and reflect on any mistakes he’s made and what he learned from them, but the President cannot answer. He desperately searches for something to say, and resolves on half-finished sentences and vocalized pauses. The film acknowledges that Bush’s silence is recognition that he’s in much deeper than over his head, not to mention that he’s never been one to impress the media with his eloquent ad-libbing.

Stone makes minor tonal distinctions between the dramatic events in Bush’s life and his major bungles, leaving the picture foggy enough so the viewer decides whether it’s comical or not, critical or not. It’s a mild stroke of genius on Stone’s part, at least from a marketing perspective, because the result caters to both audiences: Those devoutly opposed to the Bush Administration will find Stone’s cynicism light and tastefully presented, even occasionally hilarious; supporters will likely find the film fair toward the President’s errors. Furthermore, the picture is more about a lost child than a political regime, so there’s not much need for Stone to make an angrier film, as this Administration has embarrassed itself to the point of becoming a living satire. Still, one yearns for the days of Stone’s firebrand filmmaking.

Regardless, there are moments where clearly Stone enjoys a laugh at his subject’s expense. The music selected to play over Bush’s discussions of the “Iraq War” and the War on Terror, and the montages of those conflicts’ atrocities, plays with an air of Texan go-get-‘em bravura and Cavalry romanticism. Actual quotes from our President’s embarrassingly bad grammar, such as his use of “misunderestimate” and “Is our children learning?” are slipped into the dialogue. “The Most Powerful Man on Earth” being taken down by a pretzel is presented as a key signifier of his time in office, and Stone earns some hearty laughs for it. And then there’s a priceless scene in which Bush’s staff visits his ranch during one of his many “vacations” to talk shop; they follow behind him on a dirt trail, and suddenly Bush realizes he took a wrong turn back there somewhere. Everyone looks around, dumbfounded and lost.

Stone’s style and direction can sometimes feel anonymous, lacking any of the fluid cinematography or manic editing that made his 1990s efforts significant from a technical standpoint. It’s doubtful that the once-brave filmmaker of JFK and Natural Born Killers will reemerge as a risk-taker after the recent artistic failures of Alexander and World Trade Center, both exceedingly bland presentations. Stone’s helming of W. feels like an amalgamation of his before and after directorial personas—what caused his sudden deficiency of formal zeal remains in question.

W. will incorrectly be called a picture without finality, since Bush himself still resides in office upon its release, and there’s no “ending” in the traditional biopic sense. But Stone isn’t offering commentary on how history will judge this administration. (Consider Bush’s own observation: “History? In history, we’ll all be dead!”) With a hint of melodrama, the film examines the individual and why, from an emotional perspective (which in turn informs his political choices), he’s the wrong man for the job. It’s a rational and triumphant argument, with Josh Brolin’s flawless performance being the icing on the cake.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review