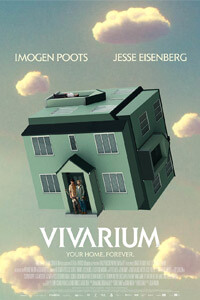

Vivarium

By Brian Eggert |

Vivarium, a bleak allegory for domesticity as a conformist nightmare, situates parenthood and suburban living firmly in the dimension of The Twilight Zone. The story of a young couple, Gemma and Tom (Imogen Poots and Jesse Eisenberg), who find themselves unable to escape a tract housing development called Yonder, might prove too real for some people currently under lockdown for the COVID-19 pandemic. The film, produced by a laundry list of international investors, has been on the festival circuit since its debut at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival. Its wide release on VOD comes in the middle of the quarantine, which is either a wholly inopportune marketing strategy or a brilliant ploy that enhances its effect. Stuck at home watching the film, it may remind you that you’re trapped inside and exacerbate your sense of internment for the foreseeable future. By the end, however, you’ll be thankful that you have it better than the characters onscreen. Think of it this way: at least you haven’t been forced to raise a freakish monster-child in the cloyingly artificial dream house from Little Shop of Horrors (1986).

Teaming again after they collaborated on The Art of Self-Defense last year, Poots and Eisenberg make a fitting pair. Her Gemma is a kindergarten teacher; his Tom is a gardener and landscaper. Hoping to find a new home together, they walk through the doors of Prospect Properties, a real estate outfit that promises affordable forever homes. Their creepy realtor, Martin (Jonathan Aris), who behaves like an alien in a human suit with unsettling grins and strange uses of language, gives them a tour of Yonder. The neighborhood’s location is “Near enough and far enough. Just the right distance,” he explains. Driving into the development of prefab homes, Gemma and Tom see a billboard that says, “You’re Home Right Now”—and it’s not a spelling error but an ominous sign of things to come. Martin shows them an available unit, Number 9, though it looks no different than any other house in the subdivision. The cookie-cutter home has a lifeless interior straight out of an Ikea showroom, and the couple laughs off the experience until they discover there’s no escape. The development’s streets prove not only labyrinthine but inescapable; no matter how hard they try to get away from Number 9, the road keeps bringing them back to its doorstep.

With no cell phone signal and all directions leading back to Number 9, the couple resigns themselves to their new home, a plastic prison where the food has an eerie non-taste, and the sky offers no wind, only tempera paint clouds. They receive boxes of vacuum-sealed food and toiletries from an unseen source when needed. And one day, a supply box comes with what appears to be a human male baby, slick with birthing fluid. Inside the box, a disturbing message reads, “Raise the child and be released.” Skipping ahead, the boy grows several years in a matter of months, and it’s no ordinary child. In a jarring voiceover effect, the weird little bugger speaks with an adult man’s voice, using it to taunt his makeshift parents. When he’s hungry, he screams at the top of his lungs until Gemma or Tom serves him. If he’s not reminding them of their imprisonment, he’s watching a television that shows nothing but freaky black-and-white patterns, recalling time-lapse footage of fungi growing on the rainforest floor. Is it the child’s language? And if so, what lessons is he learning that Gemma and Tom cannot understand?

It’s easy to admire Vivarium for how production designer Philip Murphy transforms a few simple sets and a CGI backdrop into a false enclosure that feels like The Truman Show (1998). With its uniformly green spaces and antiseptic appearance, the film, shot by the cinematographer who goes by MacGregor, carries a visual easiness in its clean lines and flat colors. In such a static environment, its only natural that Poots and Eisenberg should stand out. Both actors show their capacity for portraying a gradual breakdown. The child-thing, which becomes more intelligent and bizarre as the story unfolds, drives a wedge between the couple. Tom spends his days digging a hole in the front lawn, shoveling away feet of yellow clay—but the disturbing revelation at the bottom goes frustratingly unexplored or discussed. If Eisenberg never quite settles into his rebellious character, the emotional crux of the film lies with Poots’ Gemma, who must resist her initial temptation to nurture. After her breakout role in 28 Weeks Later (2007), Poots has continued to grow as a diverse performer in everything from soulful arthouse work (Knight of Cups, 2015) to badass genre fare (Black Christmas, 2019). She’s committed to the horrifying turns in Vivarium, enhancing the material with a monumental breakdown and a cheer-worthy final line, even if the film is a bummer.

Director Lorcan Finnegan and his screenwriter Garret Shanley have conceived a science-fiction inflected tale with questions abound. Why have Gemma and Tom of all people been chosen as parents? Why are the other houses in the neighborhood empty? Is the film a metaphor for the imprisonment of suburbia or the social obligations of parenthood? Finnegan and Shanley haven’t exactly been subtle about their imagery, however, which may lead to some unnecessary clues. The opening title sequence shows the nesting process of the Cuckoo, a bird that lays its eggs in the nests of other birds who then raise their young. Maybe Vivarium—a word that means a contained space for observing live specimens—is never more complicated than a bunch of interdimensional alien creatures using humans as parents to raise their warped little children and perpetuate their species. Finnegan and Shanley may have just wondered what would happen if a brood parasite used human beings as their host. No matter how you interpret the film, though, the result proves engaging and ultimately grim, living up to those Twilight Zone comparisons—complete with a devastating finale that leaves you to ponder this dire “What If?” scenario.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review