Reader's Choice

Villains

By Brian Eggert |

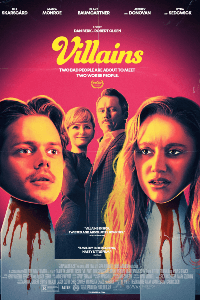

A word of advice: If you’re an enterprising criminal, don’t ever say, “This is the last one.” Because once you declare that, chances are, things will go terribly wrong. That’s what always happens in the movies, evidenced by countless stories about master thieves who find themselves in sticky situations on their final score. And it’s what happens to the two witless lovers on the run in Villains, the third feature by writer-director team Dan Berk and Robert Olsen. Bill Skarsgård and Maika Monroe play the dopey but endearing Mickey and Jules, a pair of small-time convenience store robbers who break into the wrong house while looking for a vehicle. They’re soon confronted by a married couple (Jeffrey Donovan, Kyra Sedgwick) whose criminality is far more disturbing than their own. An obvious nod to the Coen brothers and Tarantino, Villains keeps the viewer invested in the moment-to-moment tension, but it never quite delivers the laughs or pushes our limits beyond acceptable norms.

From the outset, it’s apparent that Mickey and Jules aren’t the brightest bulbs. Donning rubber animal masks that look awkward to wear, they rob the last in a series of convenience stores in the first scene and then drive away in their ramshackle car on a high, praising their performances. (The way Jules tore down the rack of chips? So badass.) Incessantly calling each other “babe,” the couple dreams of a future in Florida to start a beachside shell stand with the bag full of stolen cash and drugs they’ve accumulated. But when their car runs out of gas on a backwoods road, the couple searches for a replacement in a seemingly ordinary domestic home whose owners appear to be away. They spy a car in the garage, so Mickey and Jules break in and search for the keys. While searching, Mickey tosses aside a video camera that starts to play—and the audience sees something awful unfold that our protagonists miss. It’s a disturbing promise that the movie never entirely keeps.

The plot thickens when, in the basement, Mickey and Jules find a mute young girl (Blake Baumgartner) shackled at the ankle and chained to a pipe. Soon enough, George (Donovan) and Gloria (Sedgwick) return home, looking like throwbacks to the 1950s ideal. George feigns the look of a well-dressed salesman, and Gloria adopts the role of a Betty Crocker homemaker—but the reality is that they’re both vicious murderers. What proceeds is a darkly comic cat-and-mouse game between our naive young couple, who think they have an upper hand because they have the only gun, and the more sinister older couple, who actually have the advantage. George tries to sell them on ignoring “Sweetie Pie” downstairs and, instead, taking the car and forgetting about them. But Jules refuses to leave the girl to this couple’s psychopathic plans, whatever they are.

Berk and Olsen’s screenplay hints that perhaps George and Gloria’s twisted reality formed over time—that they were once lovers on the run, too, and that Mickey and Jules might end up the same way if they keep up their criminal lifestyle. It’s an underdeveloped idea that feels buried below the subtextual level. Meanwhile, Villains has a juicy surface. Take Gloria, whose vague psychosexual issues emerge when she ties Mickey to a bed and wants him to act out a bad boy and mommy routine. Sedgwick and everyone else in the cast are having fun playing such pulpy characters. But none of the roles have the depth to make them compelling beyond their exterior. It’s enough to know that Gloria’s desperate need to become a parent has propelled some strange criminal behavior, from kidnapping to body disposal to her fixation on a baby doll. However, most gory details remain off-screen and never push the viewer beyond a safe zone. The overdramatic score by Andrew Hewitt also accentuates that the movie isn’t as potent as it could be.

Berk and Olsen’s screenplay hints that perhaps George and Gloria’s twisted reality formed over time—that they were once lovers on the run, too, and that Mickey and Jules might end up the same way if they keep up their criminal lifestyle. It’s an underdeveloped idea that feels buried below the subtextual level. Meanwhile, Villains has a juicy surface. Take Gloria, whose vague psychosexual issues emerge when she ties Mickey to a bed and wants him to act out a bad boy and mommy routine. Sedgwick and everyone else in the cast are having fun playing such pulpy characters. But none of the roles have the depth to make them compelling beyond their exterior. It’s enough to know that Gloria’s desperate need to become a parent has propelled some strange criminal behavior, from kidnapping to body disposal to her fixation on a baby doll. However, most gory details remain off-screen and never push the viewer beyond a safe zone. The overdramatic score by Andrew Hewitt also accentuates that the movie isn’t as potent as it could be.

Although the period is never flatly stated, by the look of things, Berk and Robert Olsen have convincingly set Villains in the early-to-mid ‘90s—a time before smartphones and the omnipresent internet, which would have solved many of the challenges. It’s a fitting era, given the post-Tarantino vibes. Mickey and Jules register as a pair of natural-born softies, like Pumpkin and Hunny Bunny from Pulp Fiction (1994), and their energetic affection and dense behavior recall a dynamic seen in Raising Arizona (1987) and Burn After Reading (2009). Skarsgård and Monroe inhabit these roles well. Their “car wash” routine with Monroe’s hair is a sweet touch, and their way of getting a “creative boost” proves amusing; though, the couple’s high-pitched intensity occasionally proves grating, as do their “babes.” And while Berk and Olsen never reduce the characters to caricatures, they don’t build up the two opposing couples beyond two thin layers—what we see initially and what’s revealed later.

Animator Matt Reynolds created the end credits sequence for Villains, which shows a different movie than the one we just saw. Set to Courtney Barnett’s “Pedestrian At Best,” the sequence brings to mind a Green Jellÿ album cover, complete with monstrous figures, baked internal organs, and various dismemberments. George and Gloria never get that disturbing, disappointingly so. Maybe that’s the movie I wanted to see, something more akin to heartwarming and gory-as-hell American Ultra (2015)—another movie with animated end credits, except preceded by a movie that delivered the goods. This sequence in Villains comes after a home-video-style coda whose sentimentality and seriousness feel out of place in these otherwise blackly funny situations, leaving the viewer discombobulated from the stark and unearned shifts in tone. Berk and Olsen don’t quite have the deft touch needed to make these shifts work as they should.

Unfortunately, Villains plays at an eight, but the end credits animation plays at an eleven, and that’s the movie that could have served this scenario. Alas, the 89-minute product never entirely commits to the total morbidity of its premise. Its wobbly tonality and underdeveloped characters leave us wishing the filmmakers had explored their characters further and taken more out-there risks. Still, Berk and Olsen have a knack for genre and staging offbeat situations, and their work with cinematographer Matt Mitchell ensures a confidently composed movie. (Indeed, their most recent effort on Paramount+, Significant Other, also starring Monroe, offers a similar technical assuredness and narrative gamesmanship that prove entertaining for the brief runtime, but it doesn’t amount to much either.) Nevertheless, despite such disappointments, they’re filmmakers worth watching because there’s evident talent at work. Here’s hoping they build greater harmony between their playfulness and characters in future projects.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on October 11, 2022. Thank you for your continued support, Dustin!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review