Vicky Cristina Barcelona

By Brian Eggert |

Woody Allen’s latest film, Vicky Cristina Barcelona, actually feels like a Woody Allen film. That’s something I’ve been unable to say of his work for more than a decade now. It contains wonderfully written dialogue. The characters feel like splinters of the author’s personality. His narrative is pure fantasy with a hint of emotional realism. The unobtrusive camerawork remains unthreatening and unpretentious. And as always with his best work, Allen’s penchant for inspired casting pays off, here with names like Javier Bardem and Rebecca Hall. These are the characteristics that established Allen’s place in film history with pictures such as Annie Hall, Crimes and Misdemeanors, and Manhattan.

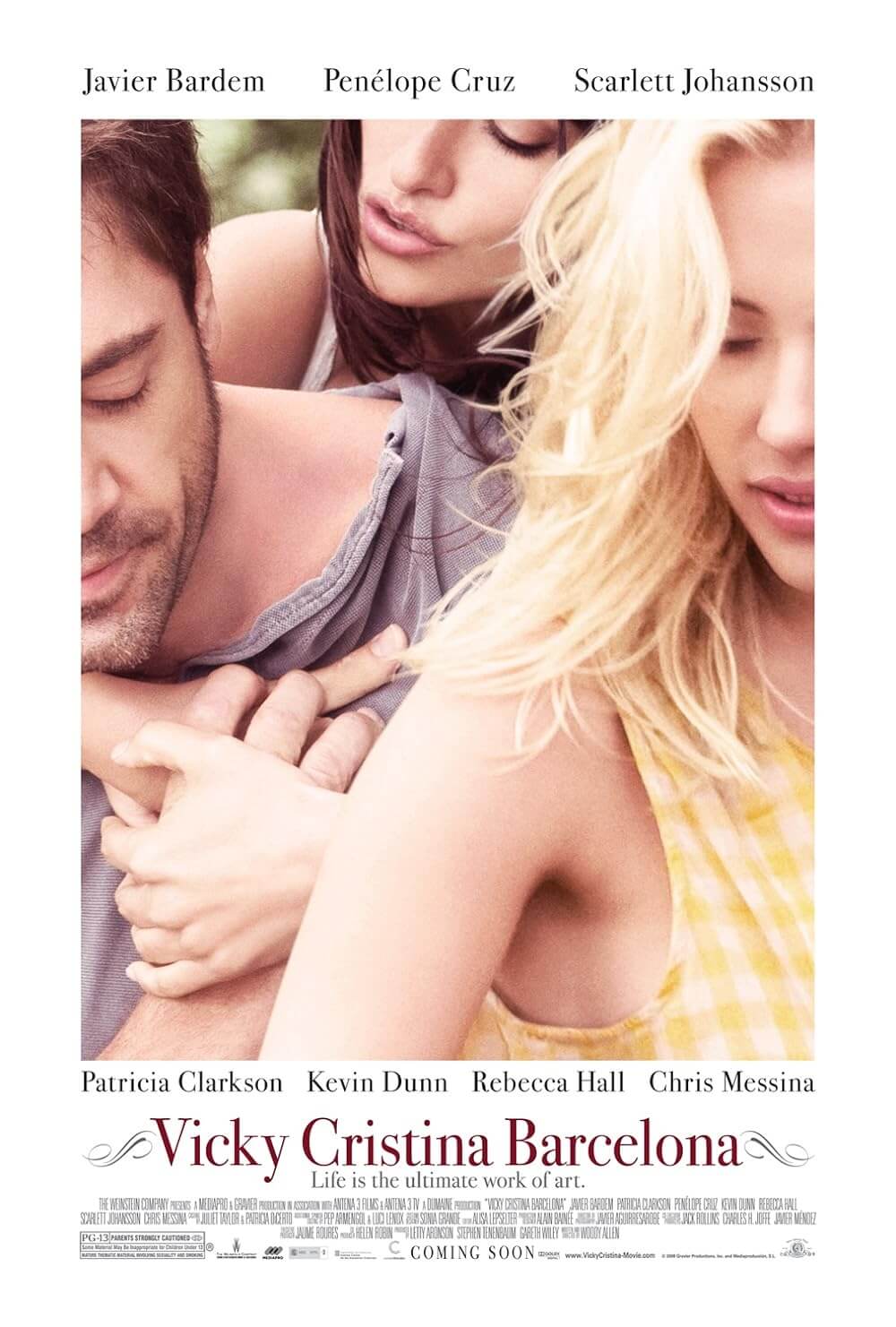

An anonymous narrator tells the story of two American tourists arriving in Barcelona for a two-month holiday in July and August. The narrator’s voice is straightforward and objective. This device is rarely effective in film, and only successful in cases where a dramatic or fantastical, or in some way unnatural, tale is told. This is how we know it’s fiction. Vicky (Rebecca Hall) is studying for her grad thesis in “Catalonian Identity” and her would-be photographer friend Cristina (Scarlett Johansson) is along for the scenery. They’re staying with Vicky’s relatives Judy and Mark (Patricia Clarkson and Kevin Dunn), the kind of Woody Allen married couple that seems frivolous at first but whose relationship, we later see, offers a preamble to the entire plot.

One night, the two Americans are approached by an engaging Spaniard, an artist named Juan Antonio (Javier Bardem) who offers them an upfront proposal: Go away with him for a weekend to Oviedo, where they will view a sculpture that has great importance to him. They will fly in his plane, stay in a posh hotel, and make love. The level-headed Vicky laughs off his frankness, while Cristina agrees, making no promises to jump in the sack. Of course, Vicky goes along with her friend, incurably annoyed with this man, his blatant advances, and her friend’s willingness to indulge them.

Juan Antonio is someone people know in Barcelona, both as a painter and for his romantic exploits, including his messy divorce from ex-wife Maria Elena (Penélope Cruz), which resulted in a near-fatal stabbing. Regardless, Vicky finds herself admitting her curious and conflicted feelings for him, despite her impending marriage to a dull American businessman, Doug (Chris Messina). Juan Antonio and his ex have a love that doesn’t work, and yet they are completely right for each other; they both claim some raw element is missing to complete their equation. The missing element becomes Cristina. Only in an emotional ménage-à-trois can Juan Antonio, Maria Elena, and Cristina find peace. I suppose their logic is that if everything is open and there’s a mutual understanding as to the nature of the relationship, what hurt could come of it? Herein resides the (typically male) fantasy.

Bardem portrays Juan Antonio as intense, romantic, and honest—the complete opposite of his character from Love in the Time of Cholera, an absurd film. And Cruz, whose Hollywood track record has been unfortunate, brings a firestorm of emotions to the screen. Clearly, she’s much more comfortable working in her own language. Johansson remains serviceable for her role, though better used in Allen’s Match Point. The real star here is not a “name” at all: newcomer Rebecca Hall is probably best recognized from The Prestige, where she played the ignored wife of Christian Bale’s character. Here she spouts Allen’s neurotic and torrential dialogue like a pro, giving it all the flavor of Diane Keaton or Mia Farrow in their days with the director. She steals the movie from the trio of well-known stars on the poster.

Admittedly, much of the film’s allure is not typical of Woody Allen at all. It has to do largely with the escapist choice of the Spanish locales. Allen and cinematographer Javier Aguirresarobe (who shot Goya’s Ghosts) serve up the beautiful scenery, painterly homes, and extravagant settings punctuated by the sculptural architecture of Antonio Gaudí. Years ago, we would expect Allen’s backdrop to be New York City, but the filmmaker, under not ideal financial circumstances, has been forced to shoot in cheaper locales. Cheaper, but by no means deficient.

London provided Allen a setting ripe with upper-class refinement for Match Point, a brilliant excursion into thriller territory; Scoop found little use of that same location. But with Cassandra’s Dream, which is not a film I would immediately designate as Allen-esque, he explored London’s seedy, murderous underworld. Reflecting on his choices of environment, we realize that aside from his signature dialogue, Allen’s mise-en-scène provides a personal stamp. Locales seem to disappear in his work, seemingly only background to lovers who walk and converse—such scenes are frequent in Allen’s oeuvre. Yet, although setting is secondary, it does not diminish its importance. He’s been writing and directing films for forty years, always in his own words, always with full control over his productions. Locations might change here and there, but they’re never unconscious of the story. He’s broadening his horizons with Vicky Cristina Barcelona to be sure, but then again, it’s as familiar and as charming as his most popular films.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review