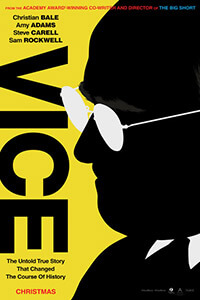

Vice

By Brian Eggert |

Writer-director Adam McKay attempts to get at the heart of Dick Cheney, one of history’s most powerful Vice Presidents, in his star-studded, politically indignant, character-assassination-of-a-comedy, Vice. But McKay’s informed and humorous approach resolves to explore only Cheney’s political maneuvers, not his motivations. Throughout more than two hours, there’s hardly any character development to speak of, besides a few personal tidbits involving Cheney’s relationships with his wife and daughters. Instead, the filmmaker uses this project as an unsubtle and angry pretext to expose what he believes lies at the former veep’s center: In a scene depicting Cheney’s 2012 heart transplant surgery, a doctor places his patient’s clogged and broken organ on a table. It fills the frame, making it impossible miss that Cheney’s heart is singed black, as if removed from the chest cavity of someone who was charred when they signed a deal with the devil in the bowels of hell. And that’s about as subtle as Vice gets.

McKay’s credits extend from comedies such as Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (2004) and Step Brothers (2008) to his acclaimed stylistic switch on the Oscar-nominated The Big Short (2015). It’s a body of work devoted to the idea that when you put a group of entitled white men together, nothing good comes of it. The same could be said of conservative politics, McKay argues in Vice, as he charts Cheney’s ascendancy from a Wyoming good ol’ boy with a couple of DUIs into a mysterious power-behind-the-throne figure. Played in caricature by Christian Bale, under the method actor’s reported 40 pounds of added weight and rather excellent makeup, Cheney remains an impenetrable character. Early in the film, during a scene set in 1963 after another drunken driving charge, his wife Lynne (Amy Adams) tells the boozy fool to clean up his act. Somehow, six years later, Cheney scores a gig as a White House intern for Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell) in the Nixon Administration. But the transition from bumpkin to political strategist is never adequately explained.

Vice is narrated from an omnipotent voice (Jesse Plemons), whose identity remains a secret until the final minutes. It’s just one of many cute, on-the-nose tricks played by McKay, reminiscent of those explanatory asides from The Big Short—featuring Margot Robbie in a bathtub or Anthony Bourdain using an old fish comparison. One of the best comes just before Cheney agrees to be the second pony to George W. Bush (Sam Rockwell, amusing). Playing down his interest in the position, which McKay demonstrates with strained fly-fishing imagery, Cheney initially declines the post to make Bush want him even more. The film then proceeds with titles that claim Cheney never became involved with politics again, that he and Lynne resolved to live out their remaining years raising award-winning Golden Retrievers, and the end credits begin to roll in a hilarious, if pointless fake-out. Back to reality, Cheney agrees to head a committee that will find Bush the perfect vice president, and of course, Cheney eventually submits himself for the position.

Once Cheney arrives in the White House—Vice skips over his years as a Wyoming congressman and the CEO of Halliburton—McKay sets aside the drama to explain in simple terms how his subject essentially controlled Washington: a disastrous combination of a weak-willed Commander in Chief and shady legal interpretations. At first, Vice feels like a sloppy attempt to recapture Oliver Stone’s brand of presidential biography in Nixon (1995) and W. (2008). But once Cheney reaches his prime in the weeks after 9/11, when he exploits the Unitary Executive Theory (to quote Nixon, “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal”), McKay forgoes creating any dramatic investment to instead put forth his unabashed hatred of his subject. The director uses all manner of formal and structural devices: models, flashy editing by Hank Corwin, saturated footage, digitally burned film stock, an enduring narrator, and the cast’s entertaining performances to keep the presentation compelling. The viewer almost forgets about the A-list cast because the material plays like a subjective political documentary, something reminiscent of a Michael Moore exposé, but with extended scenes of dramatization.

Once Cheney arrives in the White House—Vice skips over his years as a Wyoming congressman and the CEO of Halliburton—McKay sets aside the drama to explain in simple terms how his subject essentially controlled Washington: a disastrous combination of a weak-willed Commander in Chief and shady legal interpretations. At first, Vice feels like a sloppy attempt to recapture Oliver Stone’s brand of presidential biography in Nixon (1995) and W. (2008). But once Cheney reaches his prime in the weeks after 9/11, when he exploits the Unitary Executive Theory (to quote Nixon, “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal”), McKay forgoes creating any dramatic investment to instead put forth his unabashed hatred of his subject. The director uses all manner of formal and structural devices: models, flashy editing by Hank Corwin, saturated footage, digitally burned film stock, an enduring narrator, and the cast’s entertaining performances to keep the presentation compelling. The viewer almost forgets about the A-list cast because the material plays like a subjective political documentary, something reminiscent of a Michael Moore exposé, but with extended scenes of dramatization.

At one point late in the film, Bale’s Cheney turns to the viewer to deliver an acidic tirade against us, claiming that we put him into power, we wanted revenge after 9/11, and we remain complicit in the resultant hundreds of thousands of dead in the Middle East. Except, most viewers who endure the entire film (there were several walkouts during my screening) already believe that Cheney was a dangerous and cold-blooded man, and they most likely didn’t vote for him. They undoubtedly feel that the politicians responsible for Guantanamo Bay, the United States military presence in Iraq, and countless other crimes that have shaped our current predicament belong in jail, or at least not in positions of power. To be sure, it’s difficult to grasp who McKay hopes to convince with Vice. His target audience is already on his side, and so he’s lashing out at a right-wing audience who probably won’t see his film anyway.

If the purpose of Vice is to remind audiences about how angry we were throughout the early 2000s, then I suppose McKay was successful. But to what end? Does the film merely hope to remind us that Washington is a hothouse of male-dominated power, corporate influence, and morally corrupt deals to perpetuate the super-rich by duping the silent majority? Does it hope to depict how Cheney’s actions as Vice President resulted in an illegal war that was motivated by oil concerns in the United States, and how through inaction the United States allowed extremist groups like ISIS to form? Does it want to remind us that right-wing influences helped remove laws that require unbiased reporting in the media, fostering Fox News and those like it, thus perpetuating the extreme division throughout the country? If so, then kudos to all involved, who did their “fucking best” to get the secretive history of Dick Cheney right. Regrettably, by preaching to the converted, the material serves only to make us angrier than we already were, but it seldom helps us understand the subject more than we already did.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review