V/H/S/85

By Brian Eggert |

After more than a decade and four sequels since the original horror anthology V/H/S, the found footage series has shifted from a group of on-the-margins filmmakers who got their start in mumblegore to a staple of today’s thriving low-budget horror industry. With production companies such as Blumhouse, RJLE, and Shudder contributing a small wave of shoestring productions, genre imports, and cheaply made festival hits, V/H/S has risen above its modest beginnings into the biggest franchise in streaming horror. The latest installment, V/H/S/85, follows the lead of the last two—V/H/S/94 (2021) and V/H/S/99 (2022)—by giving itself a period to work within. But it has the same issues as most entries: a lame framing device that weaves between the others but doesn’t necessarily connect them, an inconsistent quality amid the individual stories, and a feeling afterward like you haven’t so much experienced a whole film as an uneven mini film festival. V/H/S/85 also plays it fast-and-loose with its aesthetic rulebook, leaving the viewer unengaged by the general conceit, while the familiar stories are more dully derivative than inspired homage.

Although past installments employed directors from the independent horror circuit—Joe Swanberg, Ti West, Jennifer Reeder, Radio Silence, and Adam Wingard—two of the new additions have directed major studio projects, including Doctor Strange (2016) helmer Scott Derrickson and, a year after taking on the new Hellraiser, David Bruckner. The other credited directors have less experience but enough to make V/H/S/85 look promising. Mike P. Nelson reinvented a franchise with Wrong Turn (2021), one of the last few years’ most twisty and satisfying horror movies. Natasha Kermani bowed Lucky on Shudder in 2020, and Gigi Saul Guerrero made Bingo Hell (2021) for the Welcome to the Blumhouse film series on Prime Video. Despite such impressive credentials, these filmmakers deliver stories that never fully engage. Mostly, they have the requisite video tape blips, fuzz, and scrambled audiovisual presentation, but at nearly two hours, the underwhelming anthology overstays its welcome.

Moreover, few of the credited filmmakers seem to understand the assignment. Consider the V/H/S franchise akin to the Dogme 95 movement (with its rules that require an on-location handheld shoot, no artificial sound or visual features, and no commercialist genres or action, among others). Similarly, the so-called found footage subgenre implies narrative and aesthetic obstructions in how the footage must look like an actual snuff film uncovered after the fact. The idea is that we’re watching something shot on home video, usually delivered in a series of long shots and captured by the same source instead of multiple cameras. The temporal limitation supplies another obstruction, requiring each short film to be a period piece set in 1985. These limitations should breed a certain inventiveness in the filmmaking, but many of the directors in V/H/S/85 ignore these rules, making several of the stories feel too highly composed and edited, rather than something real and long since buried that we’ve only now discovered and shouldn’t be seeing.

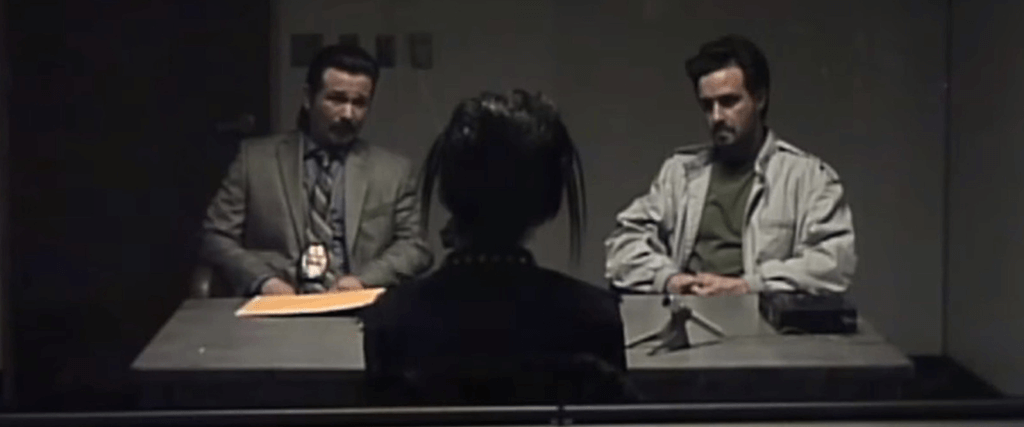

The worst offender is Derrickson, whose last short, “Dreamkill,” looks like a variation on themes from his features, Sinister (2012) and The Black Phone (2021). For starters, the presence of well-known actors Freddy Rodríguez and James Ransone as cops neutralizes any attempt at total immersion in the snuff film pretense. The story involves someone sending tapes to the police showing murders that haven’t happened yet (which look and sound suspiciously like the snuff films in Sinister). Derrickson doesn’t bother attempting a form-follows-function approach to the found footage idea; rather, he deploys multiple cameras—security cameras, interrogation footage, tapes of the slayings, etc. You begin to wonder who, in the film’s world, edited these various sources together to narrativize what happened. By the climactic shootout, Derrickson cuts to cameras that don’t have a place within the diegesis, resulting in a confusing visual agenda that betrays the basic V/H/S concept.

The worst offender is Derrickson, whose last short, “Dreamkill,” looks like a variation on themes from his features, Sinister (2012) and The Black Phone (2021). For starters, the presence of well-known actors Freddy Rodríguez and James Ransone as cops neutralizes any attempt at total immersion in the snuff film pretense. The story involves someone sending tapes to the police showing murders that haven’t happened yet (which look and sound suspiciously like the snuff films in Sinister). Derrickson doesn’t bother attempting a form-follows-function approach to the found footage idea; rather, he deploys multiple cameras—security cameras, interrogation footage, tapes of the slayings, etc. You begin to wonder who, in the film’s world, edited these various sources together to narrativize what happened. By the climactic shootout, Derrickson cuts to cameras that don’t have a place within the diegesis, resulting in a confusing visual agenda that betrays the basic V/H/S concept.

Other stories are more successful in their adherence to found footage, though they barely conceal their antecedents. The wraparound short by Bruckner called “Total Copy” plays like an episode of Unsolved Mysteries, albeit blending a 1982 double-feature of E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial and The Thing. Scientists study an intelligent alien that enjoys pop culture and can replicate anyone it sees. Elsewhere, Kermani’s “TKNOGD” borrows from David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1982) and eXistenZ (1999) in her tale about a performance artist decrying, in reverb-heavy rhetoric, how technological obsession has replaced religious icons. With winking references to “eye phones” and “black mirror,” the grisly sci-fi short finds the artist confronting a god in the machine with special effects worthy of TRON (1982). There’s a different type of god in Guerrero’s “God of Death,” which begins like a gruesome disaster movie in a Mexican city but soon descends into the sacrificial chamber of a forgotten deity. The best of the bunch is Nelson’s “No Wake,” with a group of vacationers who find themselves targeted on a lake by a lone shooter, only to realize the lake has given them the power to exact their revenge in Nelson’s second entry, “Abrosia.”

It often happens that most of the individual stories in a V/H/S movie prove lackluster, but the feature overall might prove memorable for the greatness of a single entry. (Then again, V/H/S/99 was terrific from start to finish.) For instance, V/H/S 2 (2013) contains the unforgettable “Safe Haven,” directed by Timo Tjahjanto and Gareth Evans, about a cult massacre, whereas its other stories remain passable. But V/H/S/85 doesn’t have one standout, and most of the chapters are never better than near-hits and misses. For future sequels, it might be interesting to see a back-to-basics approach that restricts the filmmakers from using CGI (copious in this series, despite the anachronism), requires them to deliver the illusion of one extended take, and generally tests their ability to innovate with limited resources. Along with the lackluster storytelling here, the filmmakers seem to have too much freedom, making the stories less of a filmmaking magic trick than they might be otherwise.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review