Reader's Choice

Valentino

By Brian Eggert |

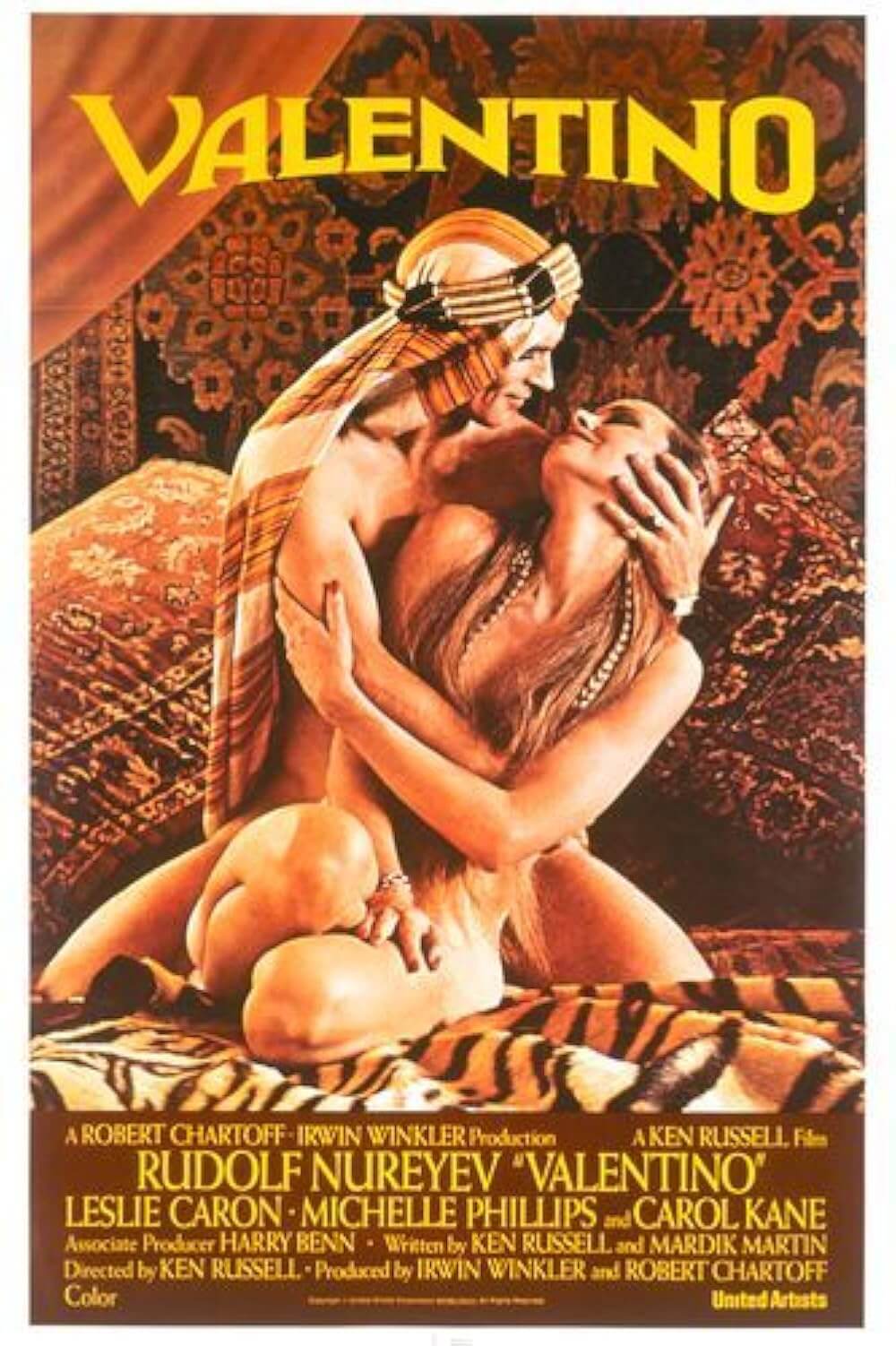

The ubiquitous celebrity of silent film stars is not like a celebrity today. Writing from experience, a person can pass through our fragmented culture and remain completely unaware of the latest YouTube personality or America’s Got Talent winner known to millions. This was not the case in the 1910s and 1920s when Rudolph Valentino was among Hollywood’s most celebrated performers, the star of The Sheik (1921), Blood and Sand (1922), and The Eagle (1925). His films earned millions in an era when it cost just seven cents for a movie ticket. Universally known, he was an icon whose death, at the age of 31, resulted in a lavish funeral attended by thousands, riots in the streets, and if it’s to be believed, suicides over the loss. But Ken Russell’s 1977 film of the star’s life, simply titled Valentino, concerns itself less with the actor’s celebrity than his lifelong struggle with image and sexuality.

In a familiar biopic structure, the screenplay by Russell and Mardik Martin opens with Valentino’s funeral. With each new visitor at the coffin, the film leaps into another flashback, each one of which has been conveniently arranged in chronological order as though the funeral attendees planned to visit according to their arrival in Valentino’s life. But rather than dwell on Valentino’s relationship with the movies or his public, Russell, ever interested in exploring sexual dimension, depicts his relationships with women and the rumors that he was gay. It could be called stunt casting that Russell placed Rudolf Nureyev, the Soviet ballet dancer whose gayness was an open secret, as Valentino. If Nureyev does not convincingly perform Valentino’s Italian accent, then at least his impressive dancer’s physique and ability to replicate the actor’s famous screen dances outdo the real thing.

In typical Russell fashion, Valentino feels like chaos, despite its conventional yet effective structure. Its wide-angle lenses, abrupt edits, and over-the-top performances could feel like insanity to those unfamiliar with Russell’s aesthetic, or those understandably repelled by it. Maybe it says something about my sensibilities as a viewer and critic, but I see the method behind Russell’s madness. Take the sequence when a young Valentino encounters Fatty Arbuckle in a dance hall; William Hootkins plays Fatty, a notorious figure himself. It’s a performance that may have informed the googly eyed gremlin from Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990) in a debauched Looney Tunes kind of way, with crazed laughter and gleeful destructive impulses. To be sure, Russell favors sensationalism and heightened emotions over biographical accuracy, and Valentino was widely criticized upon its release for its historical deviations. Those looking for a history lesson will be disappointed; those engaged in Russell’s portrait of a man desperately trying to justify himself to his public will be rewarded.

Much like the character he’s playing, Nureyev’s sexuality was questioned and mocked in his lifetime, making the film’s off-screen parallels arguably more tender today, in the wake of Nureyev’s death from complications with AIDS in 1993, than it was in 1977. Both he and Valentino were likely homosexual, and many commentators suspect they engaged in relationships with women only to keep up appearances. What’s tragic about the film is how Russell shows Valentino desperately trying to prove his masculine heterosexuality, despite some detractors accusing him of being a “powderpuff”—a running motif in the film entails a pink makeup applicator being thrown in Valentino’s face. Russell treats these scenes with appropriate tragedy and horror. In particular, there’s a sequence in which Valentino finds himself in jail, where a nightmarish group of prostitutes, vomitous drunks, and abusive police harass him about his famously large member, causing the star to break down in a puddle of his own urine. It’s a shocking, traumatic scene to watch.

Russell ends his film with Valentino defending his masculinity in the boxing ring against a reporter who accuses him of turning American men into effeminates, a match that occurred in real life in 1926 and, as in the film, Valentino won. However, Russell resituates the event as the final night of Valentino’s life, suggesting that the actor died, quite sadly, fighting to prove himself “a man,” despite having both traditionally masculine and feminine qualities. In today’s era, where defining sexual identity is rooted in proper labels and awareness, Valentino may seem simplistic. Still, it’s also rare for its time to accept that concepts of masculinity, femininity, and sexuality are not so straightforward.

Even if the viewer doesn’t come away from the film with a greater awareness of Valentino’s life and celebrity, we can at least appreciate the ornamented period details, the elaborate production values, the ostentatious performances, and Russell’s energy as a filmmaker. Russell wasn’t particularly proud of this ill-reviewed film, but it’s too strange and complex in its characterizations to ignore. Almost universally, fans of Valentino the actor have dismissed the result, whereas those who have little familiarity with his silent films or screen legacy may find Russell’s work of invention compelling.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review