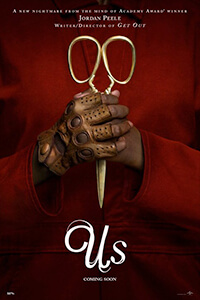

Us

By Brian Eggert |

In the first season of the original run of The Twilight Zone, there’s an episode that aired in 1960 called “Mirror Image” in which Vera Miles plays Millicent Barnes, a woman waiting for a bus. Not given to “even the most temporal flights of fantasy,” Millicent soon becomes afraid that a doppelgänger is stalking her. Justified paranoia sets in as, sure enough, her double from a parallel dimension has come to replace her. Rod Serling’s metaphysical tale was a source of inspiration for writer-director Jordan Peele, whose second film Us explores this concept in a feature-length horror story. And no wonder, since Peele will executive produce and host a new iteration of The Twilight Zone to debut on the streaming platform CBS All Access later in 2019. Peele’s second film runs more than 90 minutes longer than “Mirror Image,” and although he doesn’t explore the origins or explanations of why doppelgängers attack in any profoundly satisfying way, he nonetheless delivers a tense experience with several wonderfully crafted sequences of terror.

Peele’s follow-up to his Oscar-winning breakthrough Get Out (2017) was bound to incite enthusiasm, and perhaps even unreasonable expectations. After transitioning out of sketch comedy, Peele made one of the most impressive debuts ever put to film—a thriller that demonstrated he was both a studied filmmaker and perceptive social commentator, with a story that exposed how entrenched racism can emerge in the most unassuming of places. Us doesn’t have the same clarity of purpose, but Peele ratchets-up the shocks and suspense with the confidence of a more experienced director. As suggested by his ode to “Mirror Image,” he’s exploring referential territory here, and Us touches on slashers and the home invasion subgenre in exciting ways. Similar to his approach in Get Out, Peele cannot help but inject humor into the proceedings. And while the film should not be called a horror-comedy, it boasts some hilarious moments peppered into moments of grueling horror.

Us opens with an ominous warning that thousands of miles of tunnels exist beneath the United States, and their function ranges from abandoned subway tunnels to forgotten spaces, all beneath our feet. Then the film transitions to 1986 on the boardwalk of Santa Cruz, where a little girl named Adelaide (Madison Curry) finds herself drawn away from her parents and into a carnival attraction called “Shaman’s Vision Quest.” Inside a hall of mirrors, she sees countless versions of herself in reflection, until one of those reflections comes to life. It’s an incident that leads to post-traumatic stress disorder for the young Adelaide, who, as a present-day adult (played by the great Lupita Nyong’o), still harbors anxiety about that beachside incident. When Adelaide and her family, including husband Gabe (Winston Duke), teen daughter Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph), and young son Jason (Evan Alex), visit their vacation house near that area, she begins to notice a series of double-related coincidences that, given her childhood trauma, equate to doom.

How right she is. That night, her family is visited by four doppelgängers who refer to themselves as the Tethered, and there’s one for each family member. Each double is dressed in a MAGA-red jumpsuit, wears a single brown-leather driving glove, and carries a golden pair of scissors. “What are you?” Gabe asks them. The double of Adelaide, who talks with a raspy voice as though it’s the first time she’s ever spoken aloud, replies, “We’re Americans.” Peele turns Us into an allegory whose purpose is already being debated among critics and viewers. But rather than a straightforward commentary, he delivers a cinematic Rorschach test that allows the viewer to choose their own psychological interpretation of what aspect of Americans the Tethered represent. Some have suggested the film is about the way the United States attempts to bury its past crimes against African Americans or Native American tribes. Others claim the Tethered are not a specific historical reference but a call for Americans to pause in self-reflection and look at what we’ve become. Or maybe these alter-egos reflect the polarization of Americans in the present culture war, with the Tethered representing the silent majority who seem driven by a hatred of everyone else. With allusions to secret government projects involving control, Us lets your inner conspiracy theorist out to play.

Whatever the Tethered represent, it’s apparent that Us is more successful as a relentless tale of survival than a readable commentary. Unfortunately, the film’s openness to interpretation also bleeds into a crucial moment of plot exposition. Without going into detail, there’s a scene in which a character explains what’s going on and why, and the clarification doesn’t make much sense, leaving a few distracting plot holes that threaten to derail the film’s otherwise flawless momentum. The viewer is left asking questions: How did the Tethered become so organized? Who is feeding the bunnies (there are a lot of bunnies here)? Who supplied the red jumpsuits? If the scissors are symbolic of the Tethered cutting free from their counterparts, then why a single driving glove? Who made the underground tunnels and why? Once the viewer starts looking for satisfying answers to these questions, it becomes too easy to get caught up in the fact that Peele hasn’t provided them. Although, he leaves plenty of clues for the viewer along the way.

What works best about the film is everything leading up to this underwhelming denouement. Long before we have an inkling about why the events are happening, Us involves Adelaide and her family running and fighting for their lives against the Tethered, and cinematographer Mike Gioulakis captures the action in clear, cohesive bursts of jolting violence. These sequences feature breathless cat-and-mouse chases and shocking deaths, and a particularly good use of the supporting roles by Elisabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker as family friends. Their screeching, spider-walking doppelgängers carry eerie smiles and seem determined to unite in a statement recalling Hands Across America, the activist event of the 1980s that found 6.5 million people linked in a human chain from coast to coast. Peele also sets gruesome scenes to the diegetic presence of The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations” and another to N.W.A.’s “Fuck Tha Police,” alternating the tone between horrifying and funny. Michael Abels’ score also switches between grandiose choral chants and an unnerving nod to Luniz’s “I Got 5 On It,” another song with a significant place on the soundtrack.

Watching Us, it’s almost too easy to overlook that Peele’s cast has delivered dual performances; each is distinct enough that, from the moment the doubles appear onscreen, the physical presence and facial expressions of each signal an entirely different character—Nyong’o, Duke, and Moss above all. That’s part of what makes viewing the film such an immersive experience, despite the unclear statement and plot holes. Peele has committed most of his film’s runtime to an unyielding, scary premise that proves the filmmaker has his audience wrapped around his little finger. But whereas Get Out engaged both the intellect and our primal needs as moviegoers, Us strikes our most visceral responses before petering out toward the end. Still, Peele maintains such a high degree of interest and horror that it’s impossible not to feel the experience demands appreciation for what it achieves, but also further self-exploration about what it means.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review