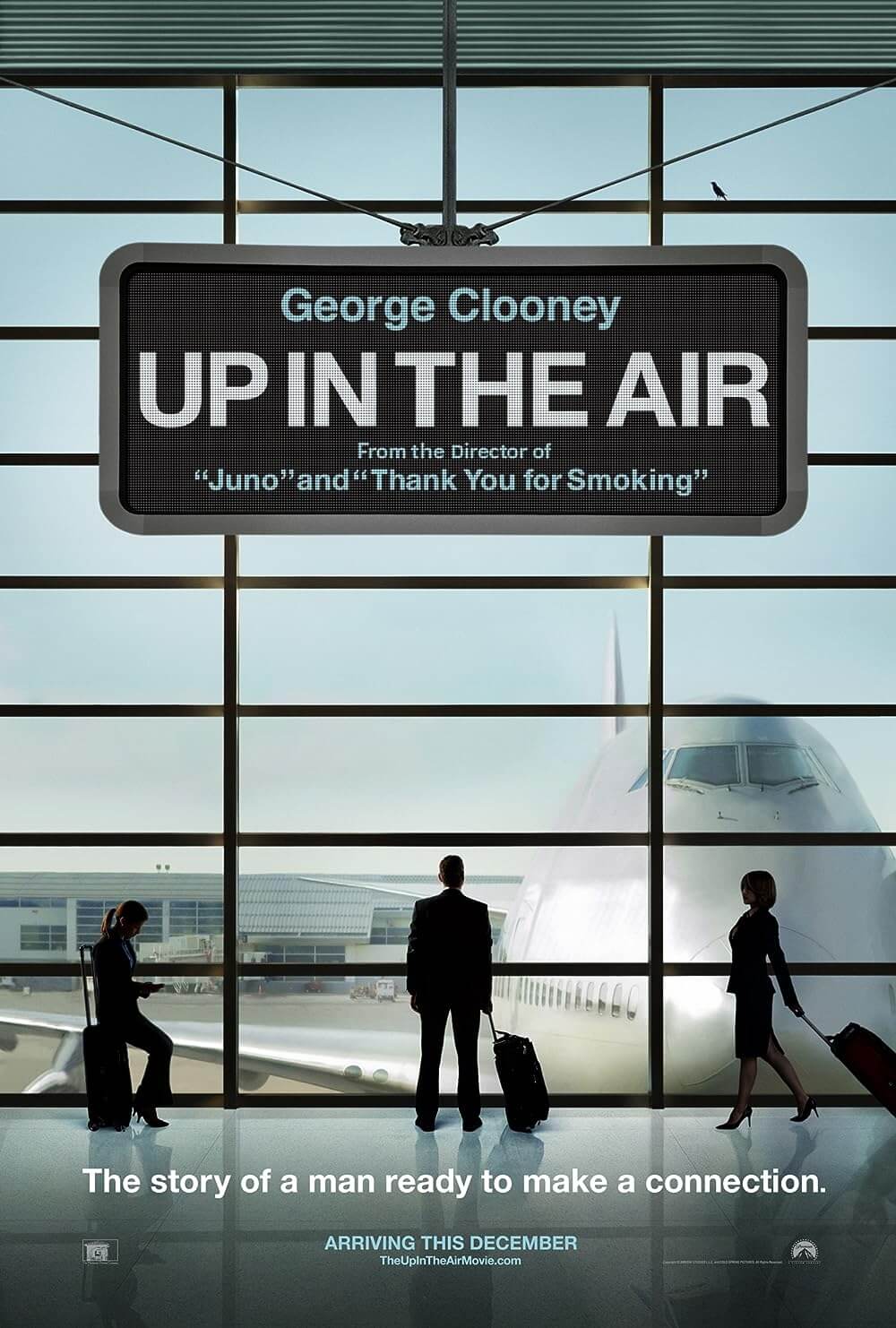

Up in the Air

By Brian Eggert |

Ryan Bingham breezes through airports with the speed and efficiency of a seasoned pro. Indeed, he’s approaching the astronomical amount of frequent-flier miles required to earn him “executive status,” which only six other people in the world have achieved. “More people have walked on the moon,” he boasts. He collects miles like a hobby and gives seminars about the joys of having no emotional ties, or as he calls it, having nothing in his backpack. Bingham’s life is spent on airplanes, flying from job to job where his trade, firing people for weak companies that can’t do it themselves, takes him. He has a one-bedroom apartment that he dreads visiting barely over a month out of the year, and he’s detached from his family. For most of us, his life might sound depressing and lonely. But Bingham loves every minute of isolation, every flourish of recycled oxygen, and phony-nice airport and hotel customer service.

Jason Reitman’s Up in the Air appears staid and bluish, as reserved formally as a deep psychological drama. The atmosphere of cold hotel lobbies and shoddy office buildings certainly doesn’t welcome an audience. But George Clooney does. He plays Bingham, a nomadic “career transition counselor” who prides himself on ushering people into the next phase in their lives, from a job that clearly wasn’t working out to a door of open possibility. He moves as smoothly through a firing as he does through airport security checks, knowing every move to make the transition as painless as possible. Forward movement means life, whereas stopping and planting roots means only a quicker death. In fact, you might say Bingham’s life exists to avoid pain—no family, no friends, just work, and no worries because of it.

Adapted from Walter Kirn’s novel by Reitman and co-writer Sheldon Turner, the film places Bingham in a situation where suddenly his job becomes irrelevant. His company, headed by a smug executive played by Jason Bateman, opts to fire people through cheaper remote video links. But Natalie (Anna Kendrick), the impetuous young go-getter who conceived the system, knows nothing of Bingham’s work and joins him on the road for a bitingly harsh tour. Adding an unnecessary impersonal touch to an already impersonal procedure, the video system grounds Bingham, forcing him to make ties. For example, the casual sex-loving female version of himself, Alex (Vera Farmiga, in another wonderful performance), goes from being a fun time to someone with whom he wants to develop roots.

Reitman’s film would not work at making Bingham so likeable through the story and direction and script alone, which are all well-crafted and socially conscious; Bingham becomes something significant through the performance of George Clooney, whose class and reverberant sex appeal have made him perhaps the most genial onscreen talent today. Those numerous comparisons to Cary Grant’s charisma and cinematic persona are spot-on. What Clooney brings to this role is not something that a writer can conceive, but it’s something Reitman could control by simply watching Clooney’s films—it’s the realization that the actor’s charms act as an illusory device within a narrative such as this, camouflaging the impending darkness of the story and making it seem somehow charming. Still, Clooney, his own life shyly similar to Bingham’s, does great work here and shows a piercing vulnerability that we’ve not yet seen from him.

This is a film that will strike debate among moviegoers, particularly because of the ending. Up in the Air seems to take a pointedly sentimental direction, but then suddenly shifts in the finale, leaving the audience to contemplate what it means. There are various ways to interpret the film. It can be read as a timely snapshot of economic unsteadiness in America, and how that instability shapes people—from those who take advantage of it, to those who cling to their loved ones in times of distress. Or, perhaps it’s simply a character study of someone who realizes their way of life has left them with nothing. But then, Reitman includes footage of persons actually fired in real-life in the end, confessing that they would not have made it through their “career transition” without their family and friends. These scenes seem to awkwardly overshadow Bingham, leaving his storyline but a symptom of a much larger disease that has weight in the film.

Up in the Air remains a painful, intelligent, and darkly comic drama that will affect you regardless of how you choose to interpret it. The son of Ivan Reitman (the producer-director behind the Ghostbusters movies), the young Jason Reitman has made only three films and accomplished varying degrees of greatness with each. The much-acclaimed satire Thank You for Smoking and the quirky comedy Juno preceded this picture, making a small but significant career for the young filmmaker. This is the director’s best work thus far, as its timelessness (whereas Juno has already become dated and irrelevant) and social reflectivity will no doubt strum a vital chord with audiences today and tomorrow.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review