Unsane

By Brian Eggert |

After almost thirty years as a director, it’s impressive that Steven Soderbergh chose to make Unsane, a tense thriller with a B-movie personality. After all, Soderbergh helped redefine American independent cinema through his Sundance success with sex, lies, and videotape (1989), won an Oscar for Traffic (2000), and has delivered a consistent body of work, granting him the rare ability to make whatever project he wants. To be sure, he’s demonstrated time and again that he’s capable of transitioning between virtually any genre, making heist comedies, a germaphobic thriller, corporate exposés, an epic biography, and a male stripper melodrama. Finally getting around to low-fi horror, the director delivers a familiar kind of yarn that can be described through the usual meets comparisons (it’s Gaslight-meets-Shock Corridor-meets-Misery). And yet, his aesthetic (shot on an iPhone) looks and feels pioneering, like the product of an innovative young student filmmaker or indie experimenter. Unsane shows Soderbergh applying his skill and trying something new; he’s always trying something new. The result is, as you might expect, as confidently composed and entertaining as the director’s most accessible output, but also disturbingly germane in the wake of the #MeToo movement.

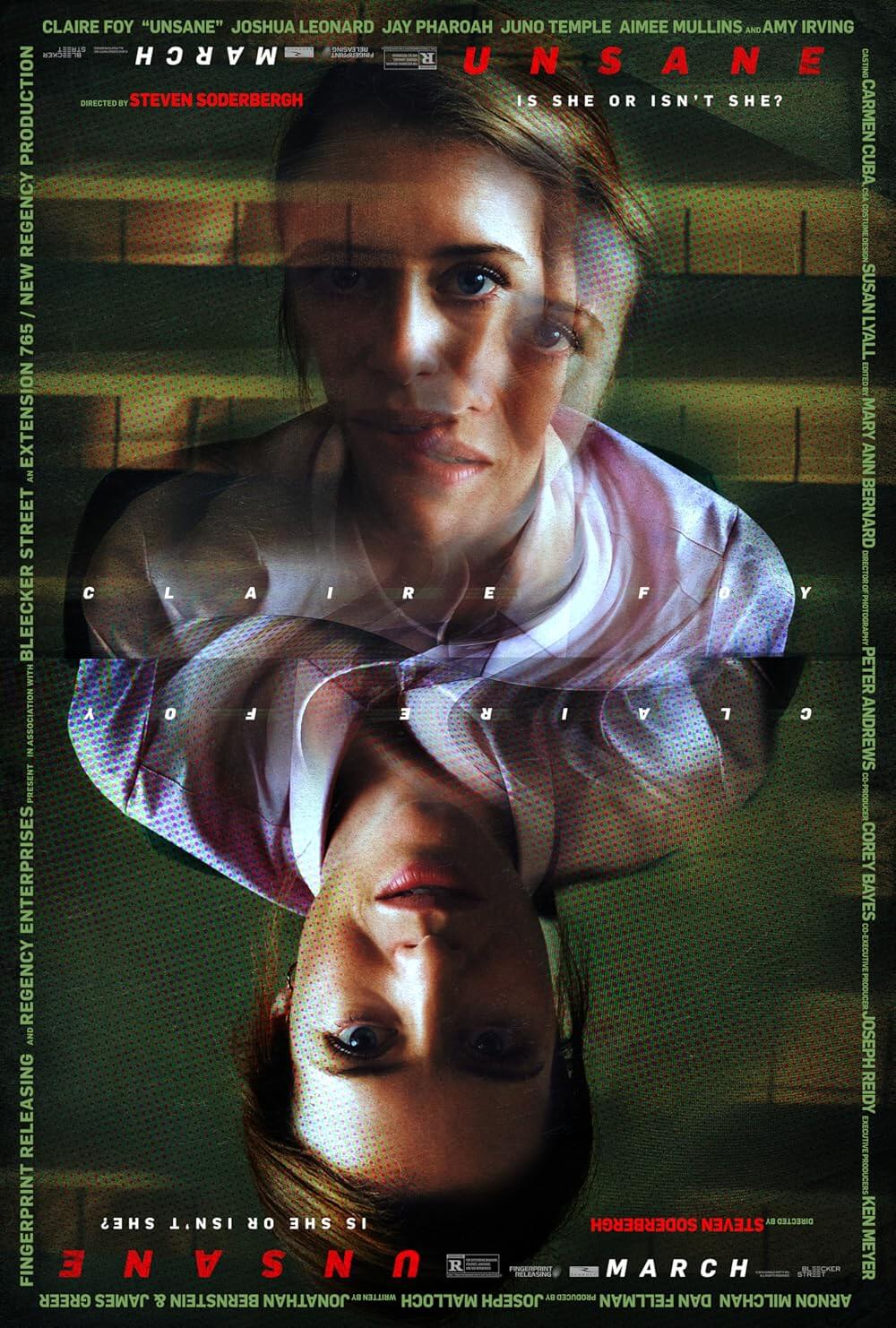

From the first shots of a blue-hued forest and a creepy voiceover delivered by the film’s resident stalker, it’s apparent that Soderbergh has divided his approach between an arthouse aesthetic and a familiar story setup. British chameleon Clair Foy, star of Netflix’s The Crown, plays Sawyer Valentini, a business analyst in need of counseling. She’s riddled with anxiety about her stalker, David Strine (Joshua Leonard), who has made her life a living hell for about two years, requiring her to move from Boston to Pennsylvania to escape his reach. To overcome her unease, she visits a mental health facility called Highland Creek. As Sawyer explains, she’s been seeing David everywhere, and she knows those fears have been playing tricks on her imagination. But after alluding to her own paranoia and thoughts of suicide, she’s duped into committing herself for a 24-hour period, which is inevitably extended when she attempts to raise a ruckus about her wrongful detainment. But much, much worse, she keeps seeing David everywhere, causing her to lash out against orderlies and incite hallucinatory flashes. For much of the first act, Soderbergh wants us to question Sawyer’s sanity. “Is she or isn’t she?” the poster asks.

Soderbergh plants a seed of doubt (that echoes everything from female hysteria to a more recent environment of informed silence) if only to punish any such disbelief in Sawyer’s claims with something far more disturbing: David has secured himself a job at Highland Creek under an alternate name, George Shaw, having fooled everyone, including the hospital’s corrupted management and the uninterested police. Given the facility’s general shadiness, the officials ignore Sawyer’s frantic claims that she’s being stalked as another symptom of her paranoia. Of course, anyone locked in an asylum against their will would find themselves at the edge of madness. Having been gaslighted and imprisoned, Sawyer remains edgy, wary about trusting anyone, and capable of violence—qualities that incite her psychiatrist to extend her stay from 24 hours to 7 days. And so, she’s left at the mercy of her increasingly disturbed stalker, who’s advanced from “We belong together” and “I know everything about you”-brand harassment to something more sinister. (When she’s threatened with solitary confinement in the dreaded basement, she replies, “Take me there right fucking now.”)

Help presents itself in the form of Sawyer’s concerned mother (Amy Irving), who must navigate a complex system of legal and medical bureaucracy to free her daughter. Inside, Sawyer befriends a genial patient (Jay Pharoah), an undercover reporter posing as an opioid addict to investigate rehab scams—as in Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963), the reporter’s scheme doesn’t go as planned. Less helpful is an unhinged and volatile patient (Juno Temple, in Killer Joe mode), seemingly determined to aggravate Sawyer to the point of an outburst and incite another round of sedatives by fed-up nurses. At the same time, there’s an intriguing (and, disturbingly, based on actual cases) undercurrent regarding mental health organizations existing for profit alone, knowingly detaining healthy patients as long as their insurance companies continue to pay. The mounting tension of David’s warped plan, combined with the shabbily antiseptic quality of the facility, leave the viewer feeling rattled for the duration. Soderbergh doesn’t shy away from the bloody stuff in the third act, either.

Help presents itself in the form of Sawyer’s concerned mother (Amy Irving), who must navigate a complex system of legal and medical bureaucracy to free her daughter. Inside, Sawyer befriends a genial patient (Jay Pharoah), an undercover reporter posing as an opioid addict to investigate rehab scams—as in Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor (1963), the reporter’s scheme doesn’t go as planned. Less helpful is an unhinged and volatile patient (Juno Temple, in Killer Joe mode), seemingly determined to aggravate Sawyer to the point of an outburst and incite another round of sedatives by fed-up nurses. At the same time, there’s an intriguing (and, disturbingly, based on actual cases) undercurrent regarding mental health organizations existing for profit alone, knowingly detaining healthy patients as long as their insurance companies continue to pay. The mounting tension of David’s warped plan, combined with the shabbily antiseptic quality of the facility, leave the viewer feeling rattled for the duration. Soderbergh doesn’t shy away from the bloody stuff in the third act, either.

Using his cinematographer pseudonym Peter Andrews, Soderbergh shoots on an iPhone 7 in a boxy aspect ratio of 1.56:1, offering a dirty digital palette in an already confined space. The cramped frame isn’t so obvious as the square Academy ratio, but it’s noticeably more narrow than we’re accustomed to, lending Unsane a claustrophobic sense of the world closing in on Sawyer. The iPhone’s lens makes everything appear off-kilter, as though we’re perpetually inside her agitated, hyper-aware state. Soderbergh gets uncomfortably close to his actors’ faces at times, creating a strange and repellent intimacy between his camera placement and wide-angle lens effect. Elsewhere, he occupies David’s voyeur perspective from behind trees or just around the corner, an old slasher trick that nonetheless works—in part because Leonard is, frankly, a creepy looking guy behind his cheery smile and soft voice (his stoner cameraman from The Blair Witch Project seems like another person). This is all to suggest that Soderbergh’s choice to shoot on an iPhone isn’t arbitrary; the visuals produce a distinct outcome in alignment with the manic story.

Although the script by Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer could use some polish on its clunky procedural details and notes of Misery (1990), Foy’s performance boosts Unsane‘s credibility. She captures the harried mental and physical state of a woman beleaguered by unwanted advances (not just from David, but others as well), followed by psychological and physical torment, without losing a sense of her character. In doing so, she reflects the current climate of awareness around sexual harassment and assault, but never in a preachy way. One terrific sequence in a padded room features Sawyer going on the offensive against David; she berates his manhood with a tirade of rejection that leads to tears (not hers) as she lists the ways in which women often feel imprisoned by male insecurities and desires. But Soderbergh toys with the audience, giving us glimpses of hope and escape through Sawyer’s brief and infrequent moments of control. Soderbergh’s manipulation of his audience is masterful, and his formal choices have a throwback appeal, curiously enough, leaving Unsane to feel like a late-night VHS screening of a cheap but memorable horror show.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review