Undine

By Brian Eggert |

Two lovers meet outside at a café. They are breaking up. The man appears stand-offish, guiltily trying to end things. The woman is more severe and insistent, and she quibbles with him over voicemail evidence that proves his desire. It doesn’t matter to him. It’s over. Then she reminds him, “If you leave me, I’ll have to kill you. You know that.” This is Undine, played by Paula Beer. Her character is based on a mythic European water nymph who can take human form and search for love on dry land. If she meets someone and he proves unfaithful, he is doomed to die. The same Greek myth inspired Danish author Hans Christian Andersen to write The Little Mermaid in 1837, French author Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué to publish Undine in 1811, and Jean Giraudoux to write a popular play about her in 1939. More recently, Neil Jordan reconceived her story in 2010’s grounded Irish fairy tale variant Ondine. However, in Christian Petzold’s Undine, the German director applies the story to his continued investigation of how contemporary Germany reconciles with its past.

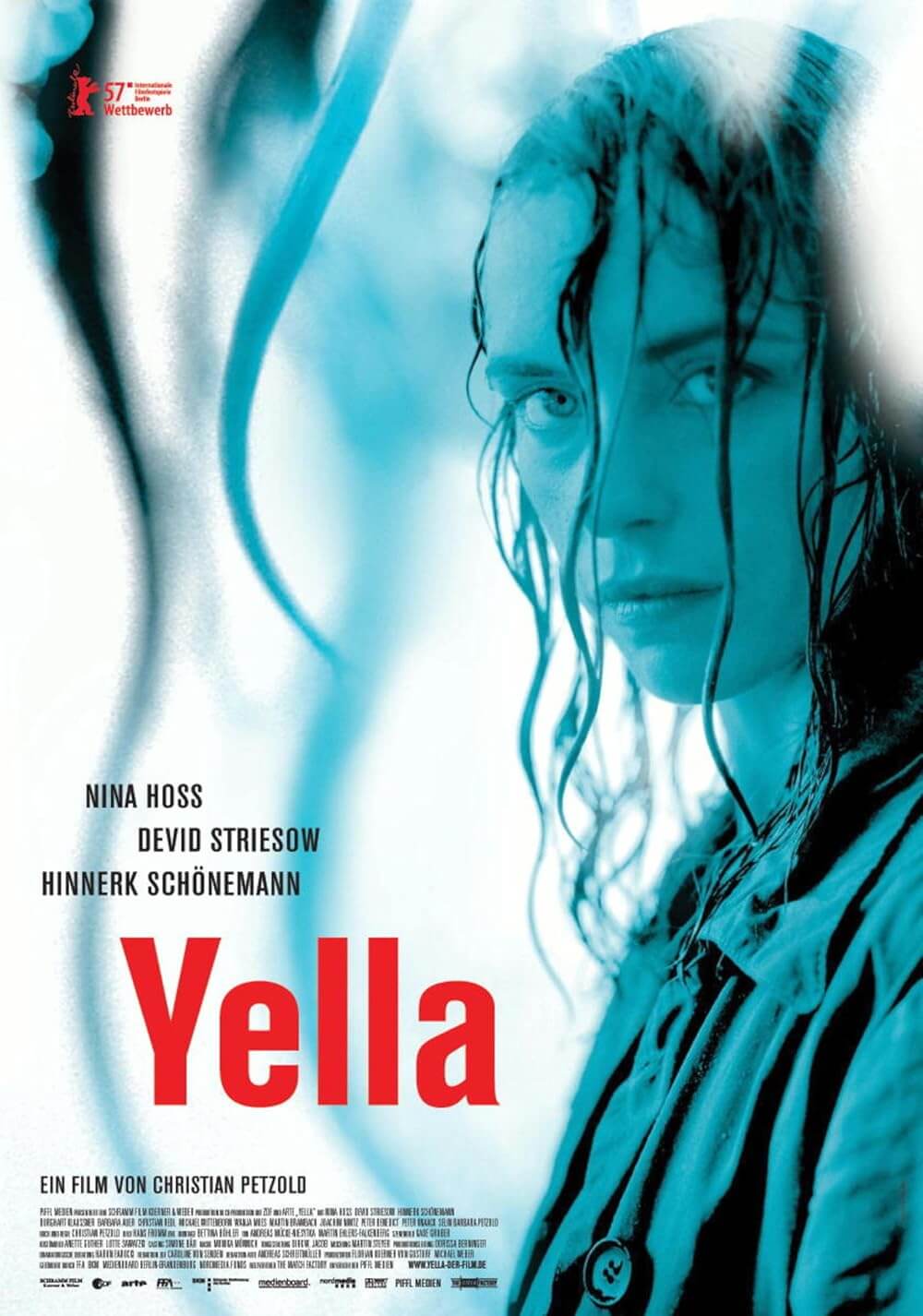

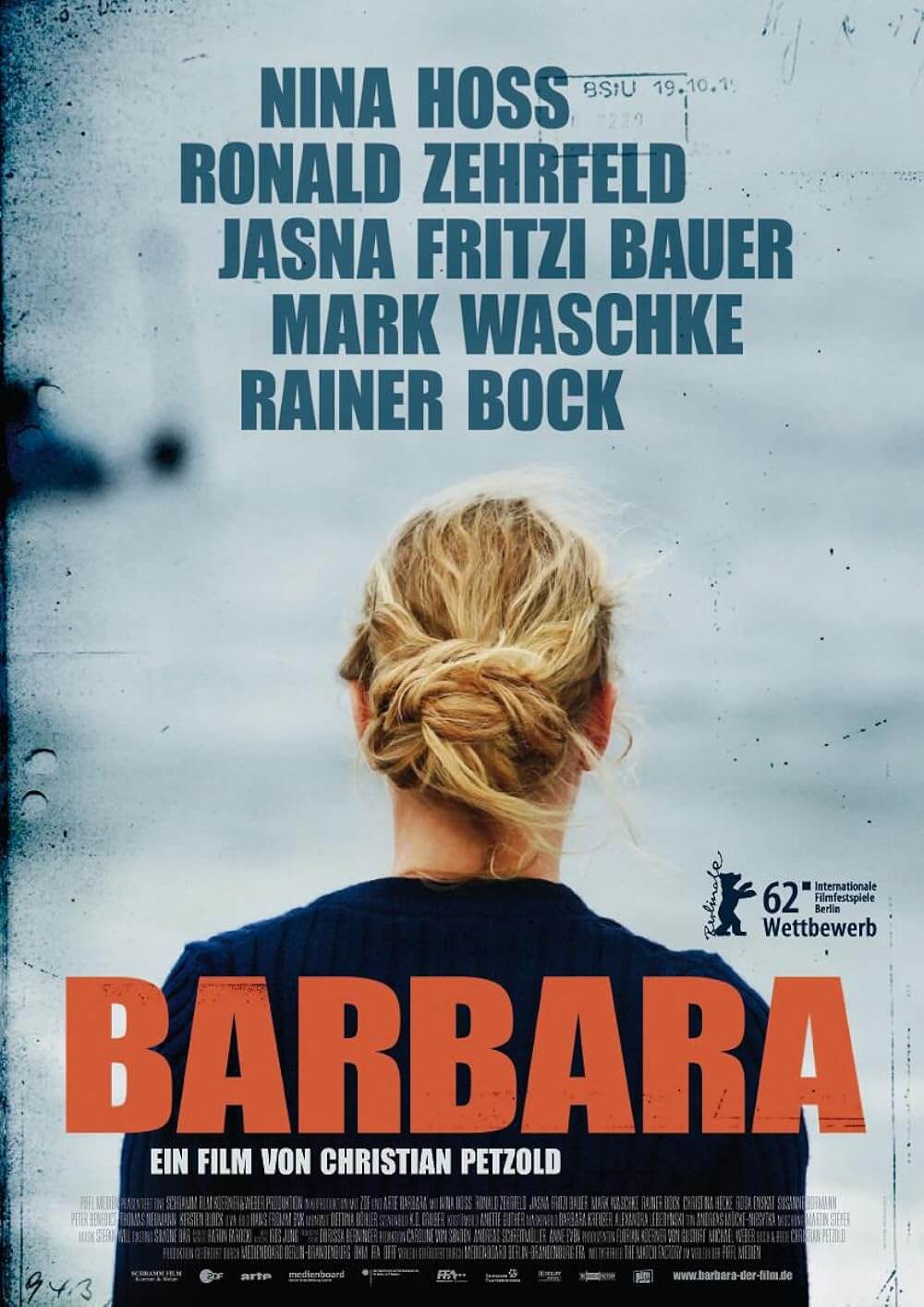

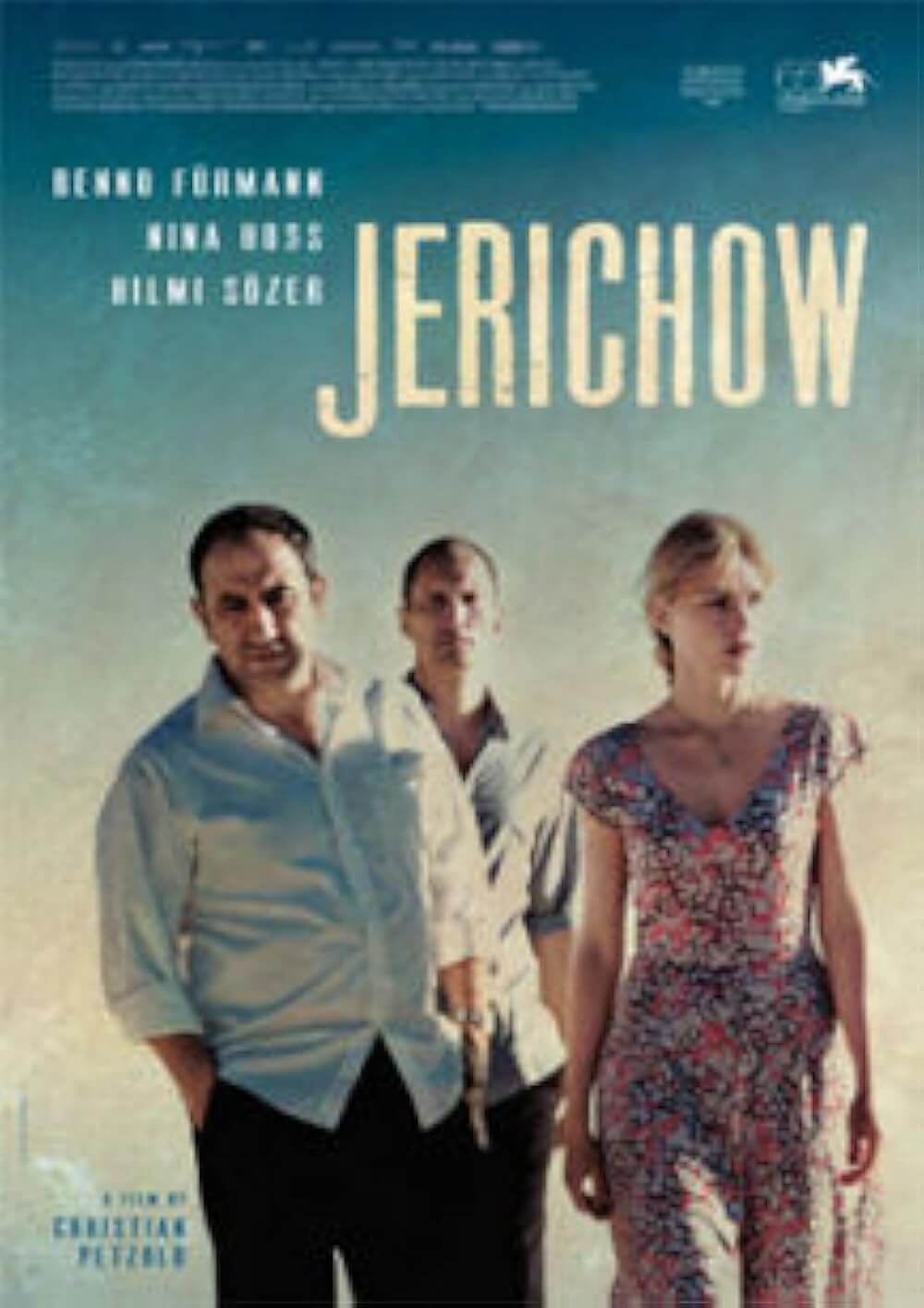

Petzold’s entire body of work has considered Germany’s fractured identity through familiar genres. His 2007 feature Yella is ultimately a ghost story that takes place in the short eternity just before a woman’s death, suggesting that post-reunification Germany is haunted by ideas of what might’ve been. Jerichow (2008) is a neo-noir whose characters represent various groups left twisting in the wind after the reunification. His best film, Barbara (2012), is a thriller about the German Democratic Republic’s oppressive eye and how that requires the titular character, played by Petzold’s regular collaborator Nina Hoss, to develop clear divisions between her internal and external selves. Of course, Germany’s history in the twentieth century would not be complete without confronting Nazism. Petzold’s Phoenix (2015) and Transit (2019) found ways of characterizing how identities sometimes fluidly change in the wake of fascism, but remnants of what came before remain in the traced history.

There’s a curious interplay of history and mythology happening in Undine. The story follows Beer’s Undine, who, after being abandoned by Johannes (Jacob Matschenz) in the opening scene, distractedly returns to the Märkisches Museum, where she works as a freelancer lecturing on the last century of Berlin’s architecture and city planning. Afterward, she revisits the café searching for Johannes and stops to look at the fish tank inside. The water in the tank seems to call out her name. A young man named Christoph (Franz Rogowski), who has just seen her lecture, walks in and asks Undine if she will have coffee with him. She is shaken, not only because Johannes has left, but the water is calling her back. All at once, the two stumble, and the tank inadvertently bursts, washing over them. It’s as though she has returned to her watery home and emerged again in the same instant. She and Christoph seem to fall in love after a few seconds of looking into each other’s eyes. Moreover, Beer and Rogowski, who starred in Transit together, have instant chemistry.

Petzold’s screenplay explores the passionate relationship between Undine and Christoph. At the same time, it devotes long stretches to Undine’s lectures about German architecture, specifically, the barrage of influence on Berlin’s city planning and the Humboldt Forum. The latter was originally a Baroque palace for Prussian royalty, but bombings during World War II left the structure in shambles. After the war, the GDR claimed the spot and built a modern Palace of the Republic in 1976, which was torn down during the reunification. The site became a subject of debate between the East Berliners and those in the West, who argued over which version of Germany’s past should be represented. The resulting non-European art museum includes a Baroque façade over an otherwise modernist building, suggesting that Germany is a complex amalgam of influences and history, artistic styles and political paradigms.

Petzold’s screenplay explores the passionate relationship between Undine and Christoph. At the same time, it devotes long stretches to Undine’s lectures about German architecture, specifically, the barrage of influence on Berlin’s city planning and the Humboldt Forum. The latter was originally a Baroque palace for Prussian royalty, but bombings during World War II left the structure in shambles. After the war, the GDR claimed the spot and built a modern Palace of the Republic in 1976, which was torn down during the reunification. The site became a subject of debate between the East Berliners and those in the West, who argued over which version of Germany’s past should be represented. The resulting non-European art museum includes a Baroque façade over an otherwise modernist building, suggesting that Germany is a complex amalgam of influences and history, artistic styles and political paradigms.

Undine’s structure echoes this dynamic through its mythological narrative, grounded by realistic production design by Merlin Ortner. The film contains few fantastical images outside of a sequence where Christoph, who works as an industrial diver, takes Undine to explore an underwater reservoir where her name is written on a long-submerged and forgotten arch beneath the surface. Undine removes her scuba gear and disappears into the dark waters. When Christoph spots her swimming alongside a massive 8-foot catfish (which locals have nicknamed Big Gunther), it’s like something out of a dream. More than once, the viewer questions whether what we’re seeing is real or imagined, part of Undine’s mythical origins or simply Christoph’s imagination as a romantic—and he is a romantic. When they say goodbye after a weekend of lovemaking, Christoph runs alongside the train like a character might do in a classic romance. Still, their grand gestures and declarations of love never feel melodramatic thanks to Petzold’s exacting restraint and Hans Fromm’s carefully composed cinematography. Undine’s most expressive flourish might be the pointed moments when the score stops, and Undine emerges from her mythic-cinematic headspace and returns to reality.

The design of the Humboldt Forum suggests that contemporary German culture changes by reformatting the past in new ways. But Undine notes a theory that suggests “progress is impossible” when the past becomes the only inspiration, which might contradict or live up to American architect Louis Sullivan’s principle that “form follows function,” depending on one’s perspective. This idea is reflected by Petzold’s choice of classical and modern music in the film, with selections from Bach as interpreted by Icelandic pianist Vikingur Olafsson and the prominent role of “Stayin’ Alive” by the Bee Gees. Both Christoph and Undine are products of their past and more contemporary experiences, whether real or imagined. And in the end, both must decide whether they will cling to those influences—they can either choose to submit to the magnetic pull of their former selves or move forward.

Christoph nearly dies in an accident in the film’s last section while welding underwater turbines and falls into a coma. Undine saves him by magical means, but the fantastical laws that control her require her to return to the water. Years later, Christoph has moved on with another woman who is pregnant with his child, though Undine’s memory still haunts him. And if Undine is to fulfill her mythological destiny, she must kill Christoph for what could be considered a transgression. Will Christoph return to his former lover? And if he doesn’t, will Undine carry out her fated revenge on Christoph as she does on Johannes? Like the director’s best work, Undine reveals itself through a layering of history, story, and entrenched lessons that is not immediately apparent, yet upon inspection, rewards the viewer on emotional and symbolic terms. As it relates to Germany, Petzold’s solution suggests that only by breaking away from its historical and mythological forces can the country heal and establish a new identity that accurately reflects its contemporary culture. Then again, isn’t all national identity an unfinished work in progress born out of cultural learning and history?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review