Underworld

By Brian Eggert |

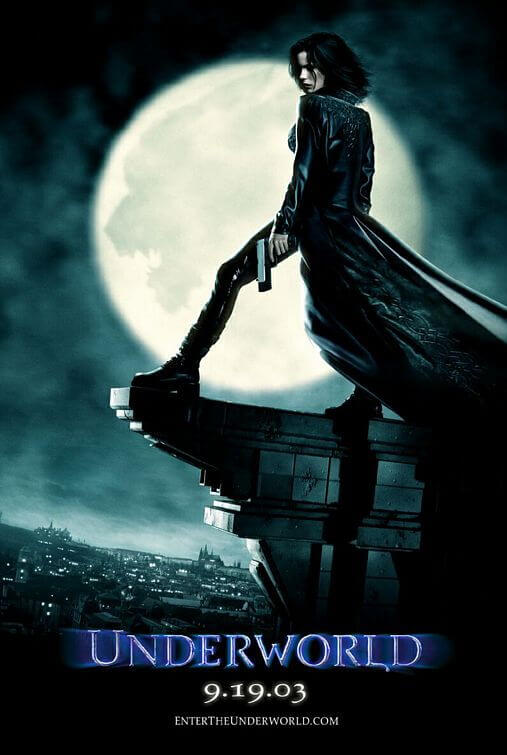

Hollywood loves to reinvent classic movie monsters in hopes of creating relevant and newly frightening versions of successful, iconographic creatures. Vampires and werewolves are among the most frequently revamped (no pun intended) for modern audiences. This is done seemingly once a year, if not more, as audiences can’t get enough bloodsucking fiends, no matter how many bad movies feature them. Underworld hopes to dwell less on the monstrosity of vampires and instead explore a world where two opposing societies engage in a centuries-old war between elitist vampires and a lowly slave race of Lycans, better known as werewolves. That they’re monsters is incidental; this is a class struggle. Essentially, the film is a modernization of Romeo and Juliet, but with monsters. And it’s more of an actioner featuring superpowered enemies than your standard horror yarn. When it’s over, the movie’s paper-thin plot and tiresome acting are only saved by the sheer gloss of the production.

The story begins when “death dealer” Selene (Kate Beckinsale) spots Lycans following a young medical intern named Michael (Scott Speedman). She discovers they’re after his bloodline, which harbors the ability to support both vampire and werewolf viruses, thus having the potential to create an amalgamated creature of insurmountable power. With Michael’s DNA providing a possible end to the blood feud, Lucian (Michael Sheen), the supposed-to-be-dead-but-not leader of the Lycans, sends his werewolf goons to hunt down the human. Meanwhile, Selene, stricken with an unexplained fascination with Michael, finds she may be in love. Her infatuation, of course, is forbidden, and so both Montagues and Capulets fight over the matter.

Director Len Wiseman fills the movie with blue-saturated cinematography and plenty of slow-motion gun battles because, apparently, the monsters’ teeth and claws aren’t interesting enough. Accordingly, there are ultraviolet light and silver nitrate bullets that take down the monsters effortlessly, making all the allure of their powers utterly pointless. Everyone is dressed in long black coats, their hair hanging down into their eyes. The soundtrack, recorded by Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson keyboardist Danny Lohner, features hard industrial rock music pumped up during fight sequences. And the characters spend more time looking cool as they get in and out of cars than they do actually going anywhere.

What is it about vampires that signify an aristocratic society? How are they always living in posh mansions with decadent clothing, believing themselves superior to the other humanoid species on the planet? Shouldn’t they be living in the sewers, only coming out at night to feed? I’ve never understood this Euro-trash depiction of vampires as an underground aristocracy. A lone vamp, such as Count Dracula, living unaccompanied in his castle and feared by Transylvanian locals, that I understand, perhaps because he’s a singular monster. But these vampire societies depicted in the Blade series and the work of Anne Rice, they’re simply too extravagant to be ignored, therefore not conducive to a vampire’s need for anonymity.

But I digress, as the fashionable depiction of vampires is not a representation likely to change. Unfortunately, it comes with a number of drawbacks. Take the Kraven character, twerp leader of the vampire covenant, portrayed with soap opera-worthy sassiness by actor Shane Brolly. He speaks every line with grave seriousness, his voice uncharacteristically nasally and pathetic, inciting laughs whenever present. Followed by equally moody vampire fashion victims, Kraven represents the stylish classicism of vampires, who always manage to combine Victorianism with Frederick’s of Hollywood garb.

Of all the movies about vampires, werewolves, or vampires versus werewolves, I suppose Underworld is one of the better ones. Without much regard for story, it has an incredible passion for surfaces. The production and costume designs were clearly labored over, but like any polished exterior that’s merely a fragile casing for an empty center, the film waves off character development for skin-tight leather and pouty brooding. Considering the basis for the story is a Gothic reinterpretation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet with monsters, that the movie didn’t follow its inspiration more strictly accounts for its failure—and since The Bard’s ending wasn’t kept, we’re also beleaguered by the unfortunate promise of future sequels.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review