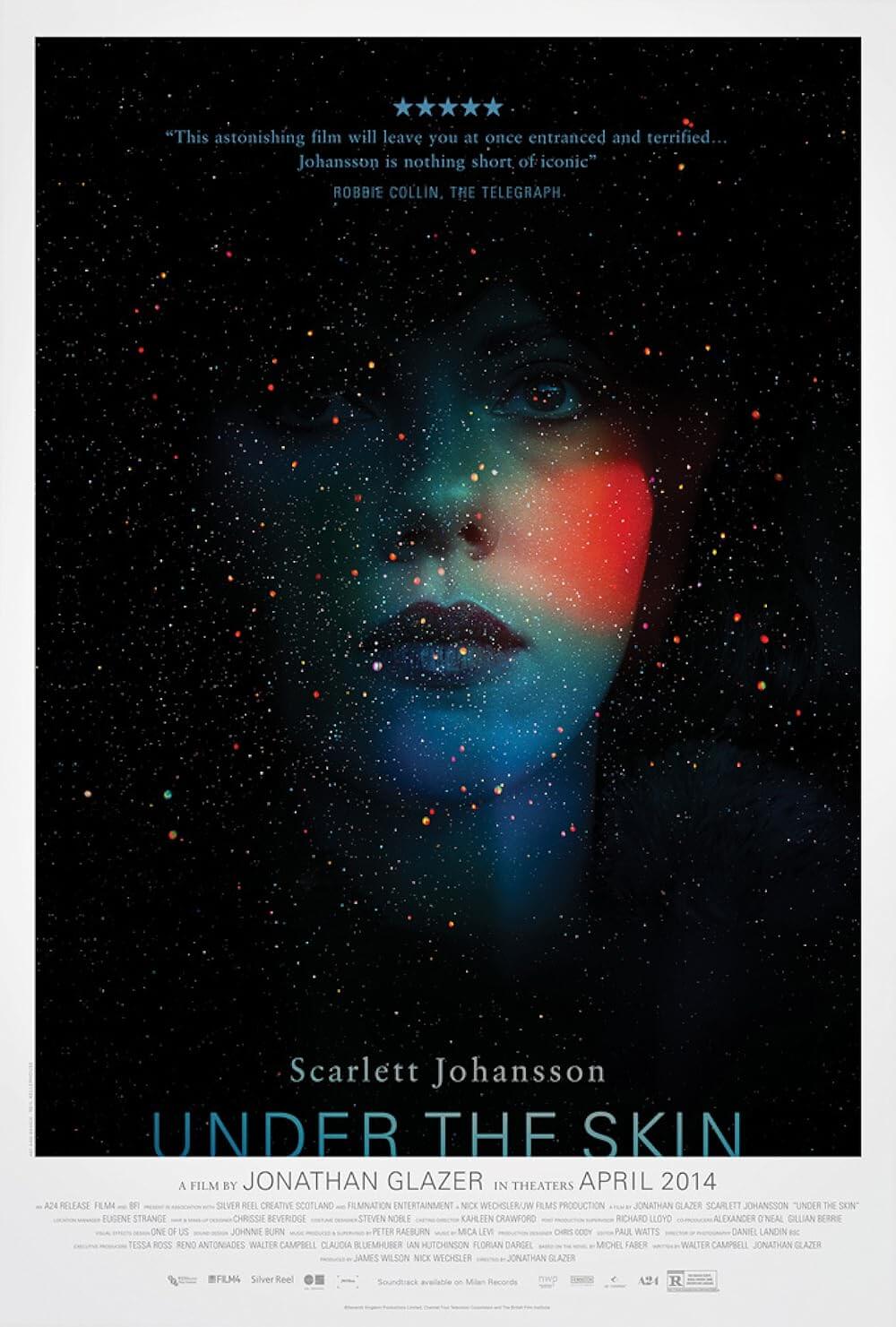

Under the Skin

By Brian Eggert |

Enveloped by black, the screen is empty until a single white dot appears. At a mesmerizingly deliberate pace, the dot shifts and forms into circular shapes that overlap and connect into some unknown configuration. Indistinct black and white outlines bring into question the negative and positive spaces before us and whether or not they’re expanding or converging, and we can only speculate as to what this process will accomplish. Will the movement converge into a spatial design such as a planetary syzygy? After all, the visuals channel the alignment from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Then again, these may be mechanical parts in the formation or detachment of a multistage rocket. Or perhaps this is a birth canal widening to deliver a new life? Whatever it is, when it’s over and the final image in the opening sequence of Under the Skin materializes into a human eye, all possibilities remain true. And though we may not grasp every detail of what we’ve just seen on an intellectual level, we’ve already been entranced by this amazing film.

British director Jonathan Glazer’s third picture in fourteen years, after Sexy Beast (2000) and Birth (2004), relies less on exposition and narrative understanding than its evocation of an emotional experience in the viewer. Based on Michel Faber’s book from 2000 about an alien seductress who gathers food for her race by luring human hitchhikers, the film was co-written by Glazer and Walter Campbell, who took more than a decade to adapt the story into a visual treatment. Within this elusive sensory experience, which borders on the purely figurative at times, the film challenges viewers to grasp its meaning. As a result, Under the Skin belongs on a short list of landmark science-fiction films that immerse their audience in the perspective of their unusual subjectivity, prompting countless questions into the film’s mysteries and meanings. Just as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner establishes the perspective of a bio-engineered Replicant in its initial scenes, or Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth embraces the viewpoint of a business-minded extraterrestrial, the first spellbinding moments of Under the Skin place us in the unfamiliar perspective of a predatory alien.

Our perceptions of Earth and its inhabitants become that of an unnamed alien, played by Scarlett Johansson. Although Faber’s book assigned the character a name, Glazer’s film avoids any specificity. After the opening moments, we see Johansson’s character naked in a white void. She removes the clothes of—what appears to be—a dead woman who has been delivered to her by a male motorcyclist, presumably our protagonist’s handler of sorts. Our heroine takes the dead woman’s clothes and emerges onto the streets of Glasgow, Scotland, where she buys her own attire. She chooses a pink shirt with a low neckline and bushy fur coat, and then she heads out in full predatory mode, driving in a van in which she seeks out lone men. She engages in conversation with isolated pedestrians on empty streets, smiles at their banter, and inquires, “Do you have a family?” and “Do you live alone?” If the answers are Yes and No, respectively, her flirtatious smile chillingly disengages in an instant, and she continues on the prowl, her expression empty as she hunts. And while the broad strokes of this setup may earn comparisons to Species (1995) and its sequels, such similarities are superficial at best—like comparing the post-modern antics of Inglourious Basterds to the poetic existentialism of The Thin Red Line, just because they’re both “about” World War II.

Our perceptions of Earth and its inhabitants become that of an unnamed alien, played by Scarlett Johansson. Although Faber’s book assigned the character a name, Glazer’s film avoids any specificity. After the opening moments, we see Johansson’s character naked in a white void. She removes the clothes of—what appears to be—a dead woman who has been delivered to her by a male motorcyclist, presumably our protagonist’s handler of sorts. Our heroine takes the dead woman’s clothes and emerges onto the streets of Glasgow, Scotland, where she buys her own attire. She chooses a pink shirt with a low neckline and bushy fur coat, and then she heads out in full predatory mode, driving in a van in which she seeks out lone men. She engages in conversation with isolated pedestrians on empty streets, smiles at their banter, and inquires, “Do you have a family?” and “Do you live alone?” If the answers are Yes and No, respectively, her flirtatious smile chillingly disengages in an instant, and she continues on the prowl, her expression empty as she hunts. And while the broad strokes of this setup may earn comparisons to Species (1995) and its sequels, such similarities are superficial at best—like comparing the post-modern antics of Inglourious Basterds to the poetic existentialism of The Thin Red Line, just because they’re both “about” World War II.

Once she finds a lone male who’s willing to enter her van and ride home with her on a vague promise of casual sex, she leads them into the dark doorway of her lair, on the exterior a ramshackle building. First-time composer Mica Levi’s eerie score, which often presents the unsettling musical equivalent of a dissonant beehive, eases into a haunting, exquisitely terrifying snake charmer’s theme. Now everything is black in a kind of dark feeding room, an abyss with no end. She walks backward as she disrobes, her prey intently following and doing the same. He continues to move forward even as his naked body sinks into the black pool beneath him, filled with ooze that, we learn later, will digest him in a nightmarish visual sequence, unlike anything you’ve ever seen. His organic material, now just a red slosh, drains away, perhaps to feed our protagonist. Or perhaps she’s just a hunter who provides sustenance for her male motorcyclist handler and those like him, who seem to monitor her progress throughout the film. But Glazer doesn’t care to spell out every last facet about what’s happening and why; he leaves it up to the viewer to speculate. Regardless if we completely understand what we’re seeing, Glazer has created images that place us in a spell.

Most of what we learn about our heroine we must cull from the leading lady’s performance, and it’s surely a tour de force, unlike anything Johansson has achieved before. Early in the film, her vacant features are mechanical, their blankness even more shocking when we realize the hunting scenes were shot in Glasgow with real-life men on the streets, who talked to Johansson without knowing it was the Scarlett Johansson, while Glazer and cinematographer Daniel Landin remained hidden in the back of the van. To be sure, Glazer made a wise choice when he cast a glamorous sex symbol in such an alluring, deceptive role. He uses Johansson’s status to instill a deliberate emotional disconnect, presenting her as an Other, a female object. But then he also draws out Johansson’s rarely tapped talents to defy her character’s assigned yet conflicting roles of feminine and masculine, predator and prey. By the end, she defies any such assignments. Gradually, her character develops what one might call “humanity” as she has sympathy for her male victims, and Johansson releases carefully measured hints of emotion on her face as her character disengages from her otherwise impassive predatory mission.

Much of what happens in Under the Skin after this point is up for interpretation, although the finale’s “reveal” is just as unequivocal—but also just as subtle—as the origami unicorn at the end of Blade Runner. Johansson’s character refuses to ensnare unsuspecting prey and finds herself in a literal fog, emerging on the other side perhaps a little more human, but not. She’s no longer a hunter, shedding her wolfish fur coat and appearing vulnerable in her pink shirt, her expressions now full of confusion, longing, and desperation to understand herself. She’s as vulnerable as her former prey. She’s human. And as her motorcyclist counterparts rocket on wet, winding Glasgow highways (reminiscent of early shots in Kubrick’s The Shining) in search of their off-reservation hunter, she explores her human side and physical identity in a subplot involving a kindly Samaritan who takes her in, the eventual dramatic turns almost comic, and yet filled with tragic irony. Through the existential second half of the film, Glazer explores what it means to be human, shifting our perception of the protagonist from a predator into the victim in the shocking, deeply affecting last scenes.

Much of what happens in Under the Skin after this point is up for interpretation, although the finale’s “reveal” is just as unequivocal—but also just as subtle—as the origami unicorn at the end of Blade Runner. Johansson’s character refuses to ensnare unsuspecting prey and finds herself in a literal fog, emerging on the other side perhaps a little more human, but not. She’s no longer a hunter, shedding her wolfish fur coat and appearing vulnerable in her pink shirt, her expressions now full of confusion, longing, and desperation to understand herself. She’s as vulnerable as her former prey. She’s human. And as her motorcyclist counterparts rocket on wet, winding Glasgow highways (reminiscent of early shots in Kubrick’s The Shining) in search of their off-reservation hunter, she explores her human side and physical identity in a subplot involving a kindly Samaritan who takes her in, the eventual dramatic turns almost comic, and yet filled with tragic irony. Through the existential second half of the film, Glazer explores what it means to be human, shifting our perception of the protagonist from a predator into the victim in the shocking, deeply affecting last scenes.

What Glazer has made with Under the Skin is a complete immersion into an alien identity, and by proxy, defines how humanity, in its purest sense, develops from empathy. Consider an early scene where Johansson’s character captures a victim at the beach and leaves behind a crying baby without the slightest hesitation, but later, as her experiences continue, she finds herself unable to feed on a gentle man with a deformed face. These narrative touches are never over-emphasized through exposition; rather, the story unfolds visually and has much in common with a silent film. Indeed, the dialogue is sparse save for the thick Scottish accents, which are almost alien-like in their unintelligibility, and contrasted by Johansson’s articulate British inflection. Through it all, Glazer’s approach is almost exclusively visual, from the handheld and mounted camera shots during the alien’s stalking scenes in Glasgow, to the rigorous austerity of her other-worldly feedings, which seem more like horrific art installation pieces. The presentation is glorious to behold, and the story unfolds only after we actively assign meaning to each beautiful image. More than once in the film—in fact, throughout most of it—I realized that my mouth was agape, and I was in complete awe of everything before me.

Often considered the Stanley Kubrick of his time, Glazer has made a hypnotic film that, just like Kubrick’s best works, challenges his audience to understand it and find the humanity within its pointedly un-human subject, but in the same instant fills its audience with wonder. We are transfixed from start to finish. Not unlike how Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey or Barry Lyndon seem cold and removed yet have overwhelming profundity coursing through them, Under the Skin contains an immediacy in every shot that demands its audience engage in a process of reflection. Such a challenge will resonate with the most discerning viewers. This is pure filmmaking, guided by Glazer’s devotion to visual storytelling and his unforgettable imagery, and further enhanced by Johansson’s impressively attuned performance. And, impenetrable though it may seem at first, Under the Skin stirs up countless thoughts and engaging conversations, and will linger in the viewer’s head long after its powerful conclusion. Though answers to the film’s infinite mysteries will be of our own making, it’s unquestionably one of the most important science-fiction pictures in recent memory. Our only regret is that it may take another decade before Glazer releases his next film.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review