Under the Silver Lake

By Brian Eggert |

Under the Silver Lake is about Sam, a disaffected 33-year-old man with a penchant for finding clues and hidden messages in ‘90s rock lyrics, classic Hollywood movies, old issues of Nintendo Power, and on the back of vintage cereal boxes. He obsesses over seemingly inconsequential details, extrapolating signifiers and connecting them to the people and events in his life. It’s a film steeped in patterns and symbols, and writer-director David Robert Mitchell hopes that, like a good mystery, the proceedings will draw you in, making you as frantically determined as Sam to crack the code. Accordingly, Under the Silver Lake has a lot of recurrent and referential imagery. Every fragmentary episode, segment, and random aside throughout this two-hour-and-twenty-minute film contains some loaded image. Mitchell has made a pastiche of L.A. noir, paranoid thriller, and psychedelic comedy, all wrapped in an enigmatic package whose central mystery leads to something more reflective. Somehow, by the end, Mitchell has rendered a commentary about self-obsession and narcissism leading to toxic behaviors—voyeurism, stalking, and the objectification of women—in stunted millennial males.

Or maybe that’s giving the film too much credit. After all, since its debut at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, the film, which was supposed to arrive last summer, has undergone a series of edits and delays to rework the experience in an attempt to make it more palatable after the initial, divisive reviews. Sure enough, Under the Silver Lake plays like something that Mitchell and his cutters were trying to discover in the editing bay. By design, the film drifts from one preoccupation to the next with a fascinating variance of style, signaled by its countless references and nostalgia. Andrew Garfield plays Sam, and a lot is going on in Sam’s life, or at least, a lot happening around his life. In his Silver Lake apartment, he sits perched on his deck, spying on the other residents à la Rear Window (1954). There’s a topless hippie bird woman (Wendy Vanden Heuvel) across the way, and a younger woman named Sarah (Riley Keough) who replicates Marilyn Monroe’s pool scene from Something’s Got to Give (1962) in Sam’s imagination. At any given moment the film refers to yet another piece of pop-culture, partly as a game for the savvy viewer; partly because Sam is obsessed with pop-culture, and he’s obsessed with himself.

Mitchell saturates the viewer in random bits of story information that, gradually, fit together into a 1,500-piece puzzle that’s 300 pieces short of a complete picture. Sam’s latest obsession, Sarah, goes missing; so does a local billionaire. Someone in the neighborhood has been killing dogs. A local artist and conspiracy theorist has created a comic zine, “Under the Silver Lake,” which alludes to the Owl’s Kiss, a neo-mythical figure who seduces and slaughters her male prey. Looking for Sarah, Sam attends weirdo L.A. parties and takes unknown substances. He investigates the music recorded by a band called Jesus and the Brides of Dracula, whose music sounds vaguely familiar. He has gory walking hallucinations about undead squirrels and dog-murderers. Following all manner of cryptic clues—among them, the conspicuous presence of the number three—he meets a homeless king and discovers an underground bomb shelter. And Sam believes all of this links to his theory that some clandestine elitists have secretly hidden subliminal codes into our entertainment for their own, nefarious uses. Oh, and a more grounded story strain, he’s about to get evicted for not paying his rent.

When Sam isn’t immersed in his own paranoia, the film gleefully occupies his gaze as a nod to the sleazier brand of Hitchcockian thriller. He follows women around, indulging his pygophilia. Topless women are abundant, almost anonymous, if not omnipresent throughout the film; however, there’s no equal opportunity nudity here. In one scene that features Sam skinny dipping in a lake, CGI blurs his genitals. Is this a conscious commentary on the ubiquity of female nudity and the male gaze in cinema? Scenes of Sam on his porch, gawking at his neighbors bring to mind Robert Altman’s L.A. noir The Long Goodbye (1973), so the nudity might be an embrace of a genre trope. Or maybe it’s just the film’s double standard? In any case, Sam’s sexual proclivities and chauvinism seep into his fantasies, daydreams, and hallucinations, all of which are specific enough that they play a significant role in his recognition of patterns. Note the scene when he finds himself on the floor of the ladies’ restroom, and he imagines the group of women shouting at him to leave as though they’re barking like dogs. This might make Sam off-putting except that Garfield’s affable onscreen presence does much to make the character somewhat likable, even if most of his behavior is contemptible—everything from womanizing to beating a few adolescents, to raising our suspicions that he’s the neighborhood dog killer.

When Sam isn’t immersed in his own paranoia, the film gleefully occupies his gaze as a nod to the sleazier brand of Hitchcockian thriller. He follows women around, indulging his pygophilia. Topless women are abundant, almost anonymous, if not omnipresent throughout the film; however, there’s no equal opportunity nudity here. In one scene that features Sam skinny dipping in a lake, CGI blurs his genitals. Is this a conscious commentary on the ubiquity of female nudity and the male gaze in cinema? Scenes of Sam on his porch, gawking at his neighbors bring to mind Robert Altman’s L.A. noir The Long Goodbye (1973), so the nudity might be an embrace of a genre trope. Or maybe it’s just the film’s double standard? In any case, Sam’s sexual proclivities and chauvinism seep into his fantasies, daydreams, and hallucinations, all of which are specific enough that they play a significant role in his recognition of patterns. Note the scene when he finds himself on the floor of the ladies’ restroom, and he imagines the group of women shouting at him to leave as though they’re barking like dogs. This might make Sam off-putting except that Garfield’s affable onscreen presence does much to make the character somewhat likable, even if most of his behavior is contemptible—everything from womanizing to beating a few adolescents, to raising our suspicions that he’s the neighborhood dog killer.

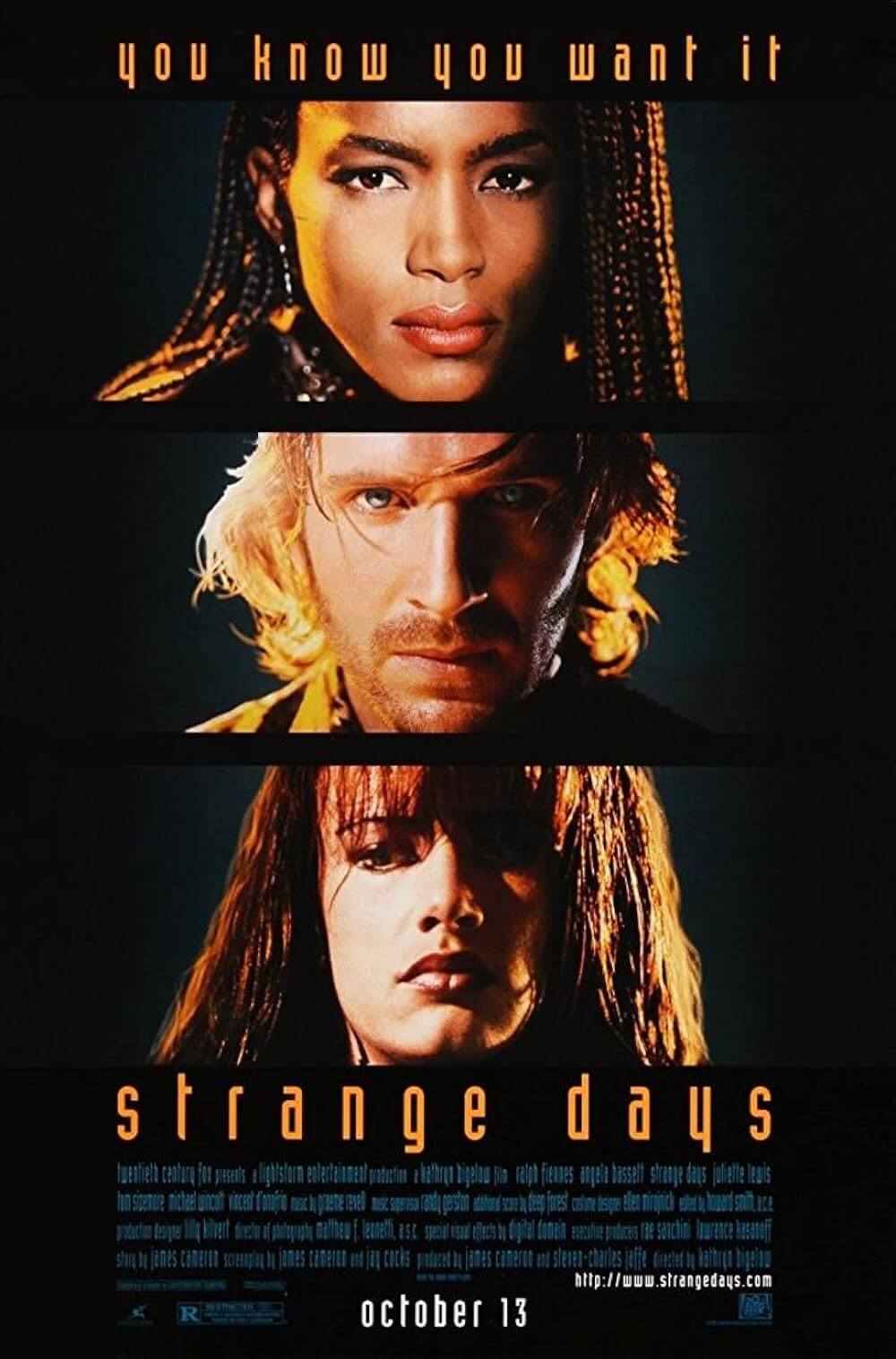

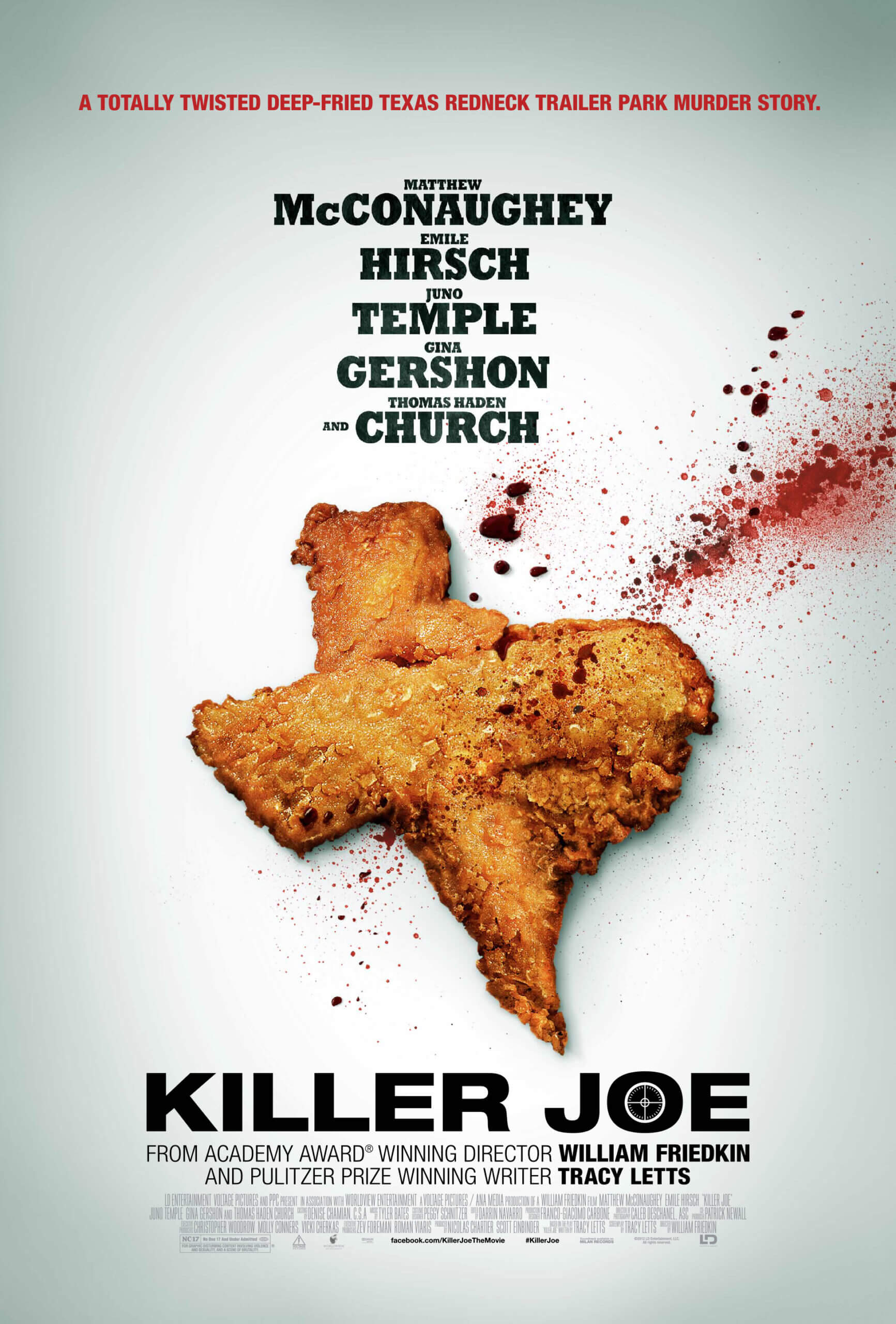

Besides The Long Goodbye, Mitchell extracts influence from the nightmares of David Lynch and the dippy humor of Southland Tales (2006), other L.A. mysteries that follow Alice down the rabbit hole. It’s no coincidence that Patrick Fischler, who also appeared in Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. (2001), plays a central role here as a fellow conspiracy theorist. And though it might be tempting to call Under the Silver Lake a work of surrealism, the film keeps the unconscious imagery as part of a conscious and ironic narrative about Sam and his world-turned-upside-down perspective. Indeed, Mitchell adds layer after layer of decipherable metatext so that watching the film puts us into Sam’s headspace. This includes an uncertain use of setting, which makes us feel unstable. Similar to how the director placed his last film, the relentless horror masterpiece It Follows (2014), in a period unto itself, Under the Silver Lake takes place in a world of “big action films based on household products,” where Kurt Cobain still lives, and all of your favorite music was written by one man.

What makes much of this enjoyable is the playfulness and confidence of the filmmaking. Mitchell and his cinematographer Mike Gioulakis, who also shot Jordan Peele’s Us earlier this year, evoke their influences, including Hitchcock and Lynch. They capture the L.A. nightlife with exquisite clarity and fluid maneuvers that keep the viewer alert, but it’s also apparent that they’re experimenting. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Body-mounted cameras, dolly zooms, movements that evoke Michael Ballhaus, and freaky shots played in reverse keep the visuals dynamic, though they can’t help but feel assembled at random. Similarly, the score by Disasterpeace alternates between grandiose orchestral revelations and suspicious little arrangements that heighten the increasingly neurotic attention to detail. If nothing else, the glossiness of the production is fascinating and admirable, even if the film leaves the viewer devoid of any lasting or deep feelings about it.

Regardless of its formal merits, Under the Silver Lake does not invest the viewer on an emotional level. One watches with detachment, trying to keep up with the erratic arrangement of styles and shifts in tone, which are fun and skillfully applied, but they lack any involvement. Rather than lead to something profound or affecting, it resolves to maintain a pastiche-as-play quality that keeps the viewer at a distance. At one point, Mitchell cuts to a bird’s eye view into a toilet bowl, and his camera pushes in from above, looking down at the waste deposit left by a rock star. The shot is handled with such import that the viewer cannot help but wonder, Is this shit somehow important? Watching Under the Silver Lake is like that. You ponder over every detail and try to put them together. It’s the effort that’s enjoyable. But once the film starts answering its questions, the outcome is unsatisfying, and there’s nothing left but to feel empty. Maybe that’s how we’re supposed to feel—just as empty as Sam. Still, embracing his self-obsession and endless male fantasies grows tiresome, no matter how critical the film may or may not be of them.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review