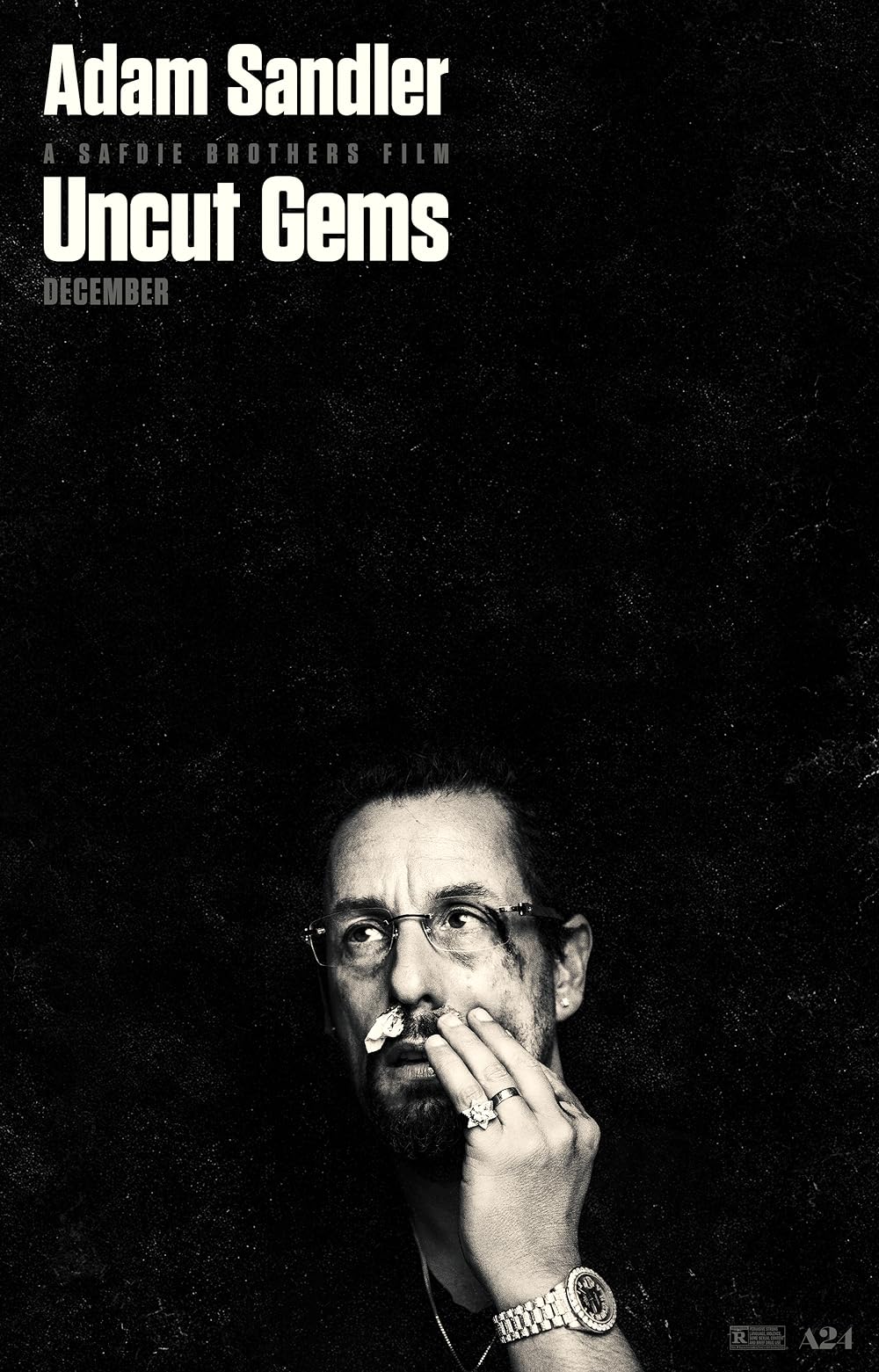

Uncut Gems

By Brian Eggert |

Uncut Gems may feel like pure chaos shot into the viewer’s brain, but it only seems that way from the countless number of reversals, switches, setbacks, and impulsive choices that befall its protagonist. Adam Sandler plays Howard Ratner, a fast-talking gambler who owns a store in New York’s diamond district. Howard’s unrelenting procession of can’t-lose hustles, unforeseen disasters, and big scores on the verge of paying off make Josh and Benny Safdie’s film an exhausting, breathless, and turbulent experience to behold. Except, every choice has been expertly rigged and wired to explode at a specific moment. The Safdies have orchestrated Howard’s life into an endless, discordant visual and aural barrage: a film of overlapping, Altmanesque dialogue; pestering cell phone calls; enforcers lingering in the distance, hoping to collect on Howard’s past-due account with a bookie. It’s a relentless disharmony that makes the viewer squirm in their seat with exhilaration and dread, as though the Safdies have tied us down in the pit and forced us to watch the pendulum swing ever closer. Though the pressure-cooker environment of the film leaves us roasting in our seats, it’s also evidence of two filmmakers in complete control of their craft.

The Safdie brothers have mastered anxiety-ridden stories about self-destructive characters perpetuating their own downfall in a series of hastily made bad decisions. Their brand of storytelling reflects the unyielding pace of their usual New York milieu, captured on actual city streets, often with real pedestrians in the shot. If there’s a template to their work, it must be Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985), a pulpy nightmare comedy that never lets up. Neither does the central character in the Safdies’ Daddy Longlegs (2009), about a dysfunctional father driven by impulse and his own sense of victimhood. The same is true of the heroin addicts in Heaven Knows What (2014), as well as Robert Pattinson’s desperate criminal in Good Time (2017)—the closest comparison to Uncut Gems both tonally and structurally. Both Pattinson’s and Sandler’s characters are interminable hustlers, exploiting every relationship and acquaintance before setting the bridge ablaze and mining another. The Safdies have replicated the DNA of Scorsese’s early work on the mean streets of New York and, with Scorsese executive producing, they have earned his blessing. But their efforts do more than merely clone Scorsese; they create a fascinating mutation whose limits reach the cosmos.

The inspiration for Howard Ratner comes from Josh and Benny’s father, who shared stories with his children about his time working in the once-great diamond district, a largely Jewish neighborhood that has been reduced to a single block in Manhattan. Howard runs a shop with bulletproof glass doors and broken buzzer, and he tries to sell iced-out Furbies to his clientele. Despite his expensive inventory, he owes thousands to a fed-up bookie (Eric Bogosian), not that his debts prevent him from pawning items he doesn’t own to secure cash for another in a long line of sure-thing bets. His wife, a strained Idina Menzel, has stopped humoring him with affection. And no wonder, since Howard keeps a mistress, Julia (Julia Fox), also his employee at the shop, in a separate apartment. But the story, set in 2012, kicks into gear with the arrival of Boston Celtics basketball champ Kevin Garnett, playing himself. Garnett is the latest client of Demany (Lakieth Stanfield), Howard’s partner who calls him a “fucking crazy-ass Jew.” Demany wrangles customers into the shop for Howard, and though the All-Star plans to buy a watch, his presence is kismet—at this same moment, Howard receives a long-awaited package. Wrapped in plastic and styrofoam and hidden inside the stomach of a bagged fish is a rare, almost otherworldly, unpolished black opal the size of a large mango.

Many critics have already compared the film’s prologue to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), but it’s the wrong Spielberg film. In the film’s unlikely, near-mythic opening at the Welo mine in Africa, two years before the main events of the film, an “Ethiopian Jewish tribe” excavates a rare black opal. After two men carefully chisel the rough gem from the rock, they examine the prisms of color inside. The shot might recall those classic Indiana Jones close-ups, where the hero’s face appears in frame with his luminescent stolen treasure. Yet, there’s a better comparison in Jurassic Park (1993), where diggers uncover a mosquito trapped in amber, and Spielberg repeats the glowing Indy shot. Deep inside the petrified sap resides the genetic material that will unleash dinosaurs onto the world once more, some 65 million years after they first walked the Earth. In Uncut Gems, it’s a small and rather ugly object with rainbow stones inside, and upon closer examination, the gem reveals endless layers and color. “They say you can see the whole universe in opals,” Howard claims later. And as the frame pushes into the opal, the shot explores an expansive universe of psychedelic imagery, recalling the Star Gate journey in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). With all the possibility of the universe contained inside, the opal might lead to good luck or certain doom. But if Jurassic Park taught us nothing else, it’s that the secrets of the limitless universe should remain untested by the hubris of humankind.

The opening sequence transitions from the opal’s spatial iridescence into Howard’s colonoscopy, implanting an immediate sense of dread over the exam’s results. If there’s another inspiration for the Safdies, it’s the Coen brothers’ A Serious Man (2009), about a beleaguered Jewish protagonist whose punishing trials—including the dreaded results of a medical exam—have almost biblical consequence. Much like the Coens’ Larry Gopnik, Howard scrambles to find some grand purpose to his life. He agrees to lend the opal to Garnett, who believes the stone to be a good-luck charm, in exchange for the player’s diamond-encrusted championship ring. It’s a temporary swap, as Howard needs the opal for an upcoming auction, where he expects it to fetch nearly a million dollars, especially with Garnett’s interest. Is the basketball player’s sudden presence a sign in Howard’s destiny with the opal? Almost immediately, Howard leaves his shop to temporarily pawn Garnett’s ring, securing him $21,000 for a bet, on Garnett’s game no less. It’s a bold move and just the latest in Howard’s juggling of maneuvers to get ahead, which proceed onward without the slightest consideration of their personal or professional consequences. Howard craves the possibility of winning regardless of the cost, and the Safdies have littered enough small victories throughout the tense narrative that we come to understand his addiction.

Throughout Uncut Gems, the Safdies follow Howard from one disaster to the next with delirious momentum. When Garnett fails to return the opal on time, an impromptu trip to Philadelphia leaves Howard betrayed and barely able to make his kid’s school play, where he’s cornered by his bookie’s muscle (Keith Williams Richards) and thrown naked into the trunk of his own car. It goes on like this without taking a single break. Even moments that seem comparatively calm, such as a Passover dinner with extended family, feel marked with doom: Howard performs a Jewish ceremony that requires him to recite the ten plagues sent down by God on Egypt, and the recitation sounds almost self-prophetic. As the circumstances and pressures keep building, the viewer cannot help but wonder how it will end. Will the low-level dealer to whom Howard gave a fake Rolex suddenly appear in the finale, similar to Benny Blanco from the Bronx in Carlito’s Way (1993), and deliver an unexpected bullet? Or will Howard prevail from this 134-minute spiral and, miraculously, hit bigger than ever before, in the manner of Bob le flambeur (1956)? The climactic scenes have an infectious energy and see the world through Howard’s eyes, optimistic about his chances and certain of his strategy, yet oblivious to the reality of his situation.

Howard’s dizzying series of pleading apologies, empty promises, and breakdowns of self-hatred have been perfectly captured by Sandler, who has rarely been better. Sandler is best when he’s playing ambitious characters of sensitivity, temper, and weakness, whose inner lives represent a massive wound that externalizes at critical moments, as seen in Punch-Drunk Love (2003) and The Meyerowitz Stories (2017). Howard may be a despicable character, but there’s something about him that makes the audience root for his victory. He’s a terminal loser, closely drawn from George Segal’s hopeless gambler in Robert Altman’s California Split (1974), but following his journey is like some kind of narcotic. Collaborating with cinematographer Darius Khondji, the Safdies follow Howard in a manner that feels organic and urgent, and the immersive editing, achieved by Bennie Safdie and co-writer Ronald Bronstein, relays space with surprising clarity for such a turbulent and ever-moving experience. However, that’s the genius here. Uncut Gems is such a mesmeric watch that it tests one’s ability to keep track of exactly how it was achieved, and the film may require a second viewing to fully appreciate.

Howard’s dizzying series of pleading apologies, empty promises, and breakdowns of self-hatred have been perfectly captured by Sandler, who has rarely been better. Sandler is best when he’s playing ambitious characters of sensitivity, temper, and weakness, whose inner lives represent a massive wound that externalizes at critical moments, as seen in Punch-Drunk Love (2003) and The Meyerowitz Stories (2017). Howard may be a despicable character, but there’s something about him that makes the audience root for his victory. He’s a terminal loser, closely drawn from George Segal’s hopeless gambler in Robert Altman’s California Split (1974), but following his journey is like some kind of narcotic. Collaborating with cinematographer Darius Khondji, the Safdies follow Howard in a manner that feels organic and urgent, and the immersive editing, achieved by Bennie Safdie and co-writer Ronald Bronstein, relays space with surprising clarity for such a turbulent and ever-moving experience. However, that’s the genius here. Uncut Gems is such a mesmeric watch that it tests one’s ability to keep track of exactly how it was achieved, and the film may require a second viewing to fully appreciate.

Uncut Gems cannot be called a pleasant experience. It’s like being forced to take a double dose of uppers and dance barefoot on a floor littered with broken glass. Much like Good Time, it thrills even as the viewer recoils from the frantic ride and the strained morality of its central anti-hero. Many will reject the film as unpalatable and deeply nasty, but it’s an unquestionable joy when filmmaking of this caliber propels the viewer and manipulates us at every jittery turn. From the Safdie’s oversight of the film’s squirm-inducing scenes to the brilliant, hypnotic score by Daniel Lopatin (aka Oneohtrix Point Never), which sounds like the lovechild of Vangelis and Tangerine Dream, Uncut Gems never stops stimulating. All the while, Sandler’s performance is so pitch-perfect, just the right blend of detestable yet charming, that he almost makes us forget about our foreboding. What could be more appropriate for a compulsive gambler who fails to recognize his pattern of behavior? It’s a testament to the Safdie brothers’ enveloping schema that, in the climactic scenes, when Howard seems to have masterminded his escape from under the boot of his many creditors, we actually believe he might come out ahead.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review