Twixt

By Brian Eggert |

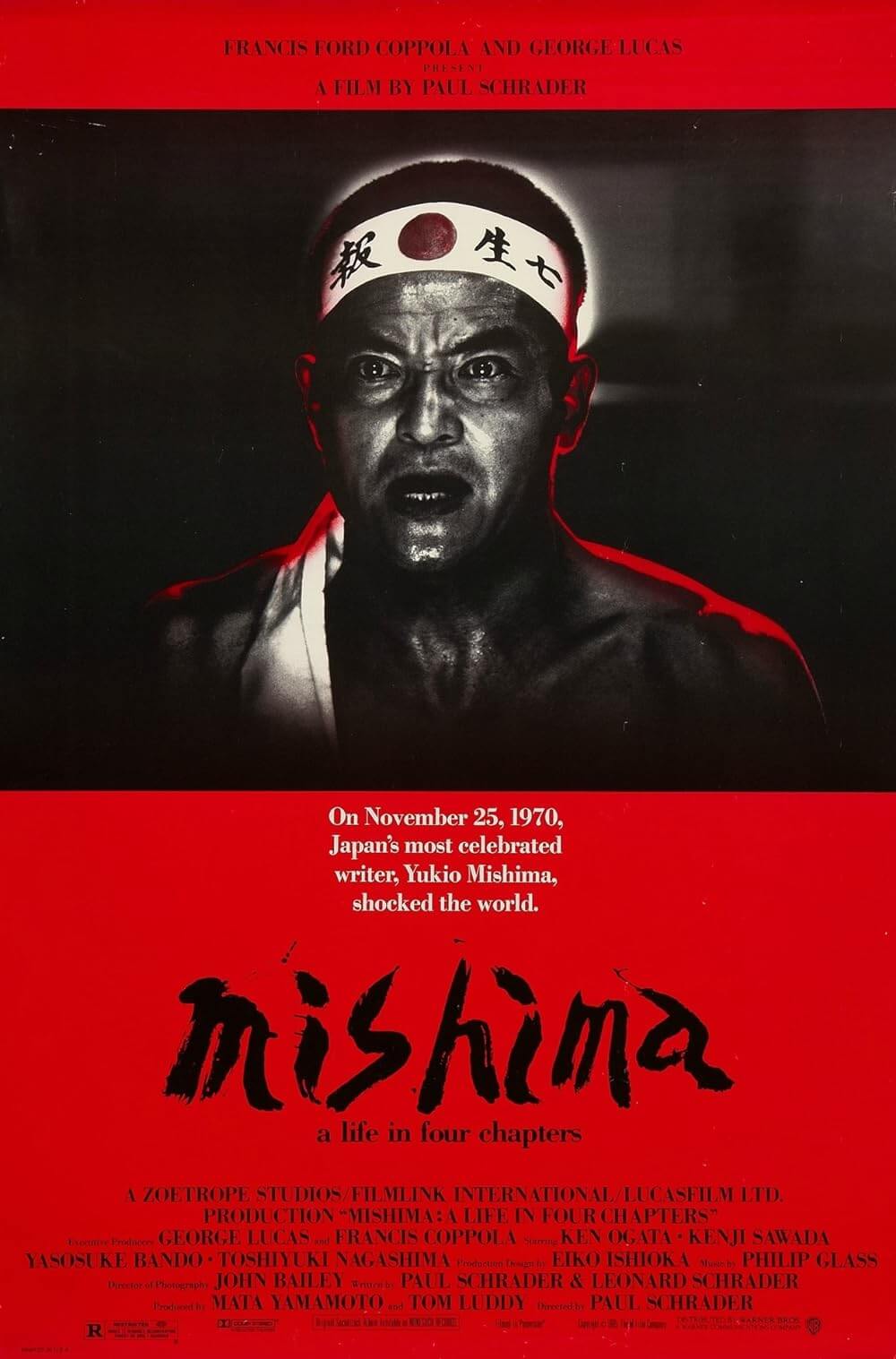

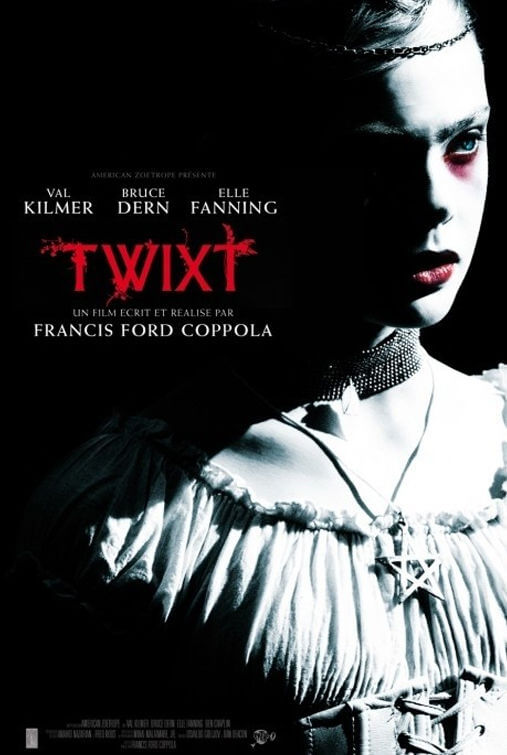

Once a preeminent filmmaker of Hollywood’s post-classical period of the 1970s alongside the likes of Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola has long since settled into comfortable independence, having veered away from commercial cinema in the last two decades in favor of low-budget, underseen arthouse films. In 2007, he returned after a 10-year hiatus with Youth Without Youth, an increasingly contrived rumination on everything from philosophy to language to metaphysics, all wrapped in the veneer of a supernatural spy yarn. Two years later, he released Tetro, a drama about the binds of family, and his overabundant craftsmanship outweighed the familiar narrative with a decidedly indulgent style. With his latest, a gothic horror tale called Twixt, the director self-financed the picture, which was primarily shot on his estate in Napa County. It played on the festival circuit in 2011 and 2012, but the film was never picked up for wider distribution. The majority of audiences who care to discover the film will do so on home video and VOD.

Crediting a nightmare as his source material, Coppola’s film opens with atmospheric narration by Tom Waits, recalling one of the musician’s own creepy verses, “What’s He Building?” We’re introduced to the sleepy town of Swan Valley, where cut-rate horror author Hall Baltimore (Val Kilmer) arrives at a hardware store signing for his latest book on witchcraft. Quickly immersed in local stories about the town’s sordid past, Baltimore listens to townsfolk talk about how the old clock tower, which reads a different time on each of its five clocks, is inhabited by the devil. Sheriff Bobby LaGrange (Bruce Dern), an avid Baltimore fan, tells him about a series of child killings from 1955 and how the children’s ghosts still haunt the town. But then the loopy Sheriff also makes bat houses and claims the local bunch of emo teens are vampires, so how credible can he be? Meanwhile, Baltimore begs his publisher (David Paymer) for an advance on his next book, if only to appease his disagreeable wife (Kilmer’s ex-wife Joanne Whalley, curiously enough).

An idea for a new novel comes to Baltimore one night when he’s visited in a dream by the ghost of a murdered girl (Elle Fanning), who may be a victim of the 1955 killings or perhaps died in a more recent murder still fresh in the local morgue. The film’s frequent dream sequences are shot in such a muted tone by cinematographer Mihai Malaimare Jr. that they might be mistaken for monochrome. Each sequence borders on black-and-white but then contains another bright color in the frame, such as a yellow lantern or red curtains—a visual formula reminiscent of Robert Rodriguez’s Sin City. Theatrical screenings of Twixt even featured two 3-D sequences for which patrons were asked to put on glasses, albeit just for a pair of scenes. As the writer wanders around in his own dreams, he learns more about Swan Valley, and even how to structure his latest novel from a powder-white Edgar Allen Poe (Ben Chaplin). Amid Poe’s descriptions, which are littered with details from his own work, we hear about the town’s population of ghosts and vampires. And when Baltimore wakes up, he’s pestered by the Sheriff to collaborate on a book about a vampire execution chair.

This mishmash of ideas—ghosts, vampires, haunted clocks, burnt-out hotels—never quite comes together in a satisfying whole. The film moves from one idea to the next like the vague merging of passages in a dream. The tone shifts just as freely, from grave forays into the town’s past to the humorous asides between Baltimore and his publisher. Although, intermittent moments of inspiration do occur. Take the sequence where Kilmer’s writer sets up his ritualistic writer’s table with packages of beef jerky and Irish whiskey. Then we see the actor improvise a series of drunken impersonations, beginning with his spot-on versions of Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now, James Mason, and a gay Black basketball player from the 1970s. Though pudgy and playing a character that doesn’t require much range (he’s described as a second-rate Stephen King), Kilmer is likable enough in this one-note role. Dern is far more enjoyable as the batty sheriff, the kind of role in which this actor has specialized in his elder years.

A curious autobiographical streak exists in Twixt too. Not only does Baltimore rely on his dreams for his next project as Coppola has, but Baltimore is haunted by memories of his teenage daughter who died in a speed-boating accident; Coppola lost his son Gian-Carlo in 1986 to a similar accident. In a scenario populated by tongue-in-cheek humor and silly horror tropes, these outwardly personal touches feel out of place. Much like Youth Without Youth and Tetro, Coppola instills admirable details into every frame and tests the medium with the verve of a film student, an odd quality, given the seasoned filmmaker’s long history of immaculate mise-en-scène. One gets the impression that Coppola had a lot of ideas in his head and wanted to try out some technical tricks at the same time, and so he spun everything together into this inelegant product, the end result of which concerned him very little. An ironic choice, given that Baltimore’s publisher demands a “bulletproof” ending for his next book, yet neither the ending nor the beginning nor middle of Coppola’s latest could be described as such.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review