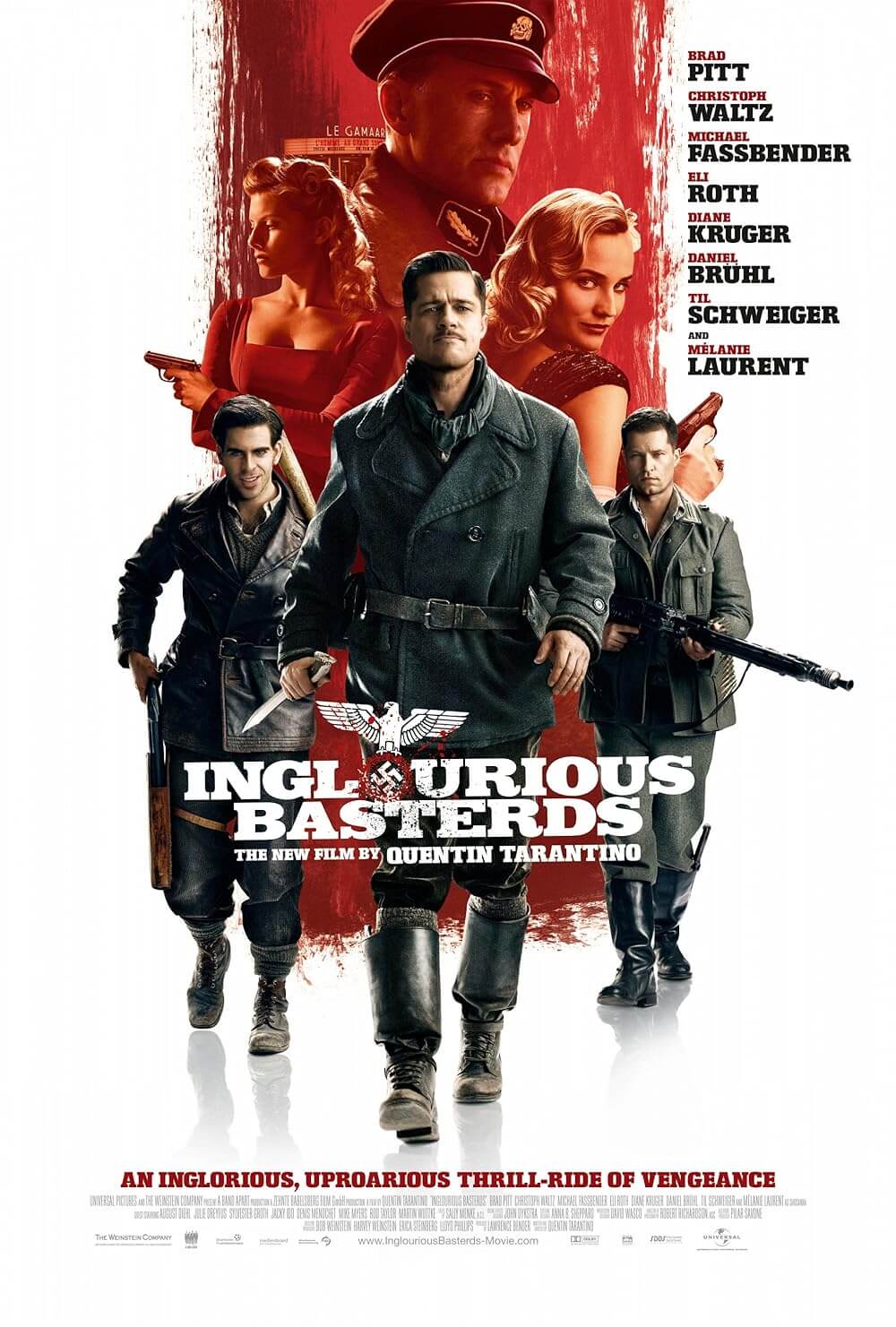

Trumbo

By Brian Eggert |

Imagine a Hollywood community so concerned with their perceived moralist standpoint that they set aside almost guaranteed box-office numbers to oust someone just for their political beliefs. Such was Tinseltown after World War II, until about 1957, when the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) sought out suspected communists in the film industry. Trumbo, about Roman Holiday and Spartacus screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, tells a smart and funny story about the blacklisted writer who fought the unconstitutional anti-communist system. Informative for those unfamiliar with HUAC and a lark for those who are, director Jay Roach and writer John McNamara’s entertaining picture excels because of several fine performances from actors playing classic Hollywood figures—the foremost of which is Bryan Cranston as Trumbo.

Roach’s comedy track record (Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery and Meet the Parents) may not seem suited a period piece with such a significant political undercurrent, but he also helmed political-minded features like Recount and Game Change for HBO. Based on Bruce Cook’s biography Dalton Trumbo, the film takes the perspective of its subject writer; this means the story written from the perspective of the winners and some could take issue with its lack of objectivity and criticism of the U.S. government. However persecuted by Hollywood and the Joseph McCarthy’s witchhunt, in a movement co-spearheaded by powerful gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren), as well as Congressman J. Parnell Thomas (James Dumont), the blacklisted writers known as the Hollywood Ten became underdog legends. Over time, of course.

With an ever-present cigarette holder in his mouth, a tumbler of Scotch in his hand, and his body soaking in a bath, Trumbo punched away successful scripts for Hollywood. When his active status as a “card carrying member of the Communist Party” became a problem for Hopper and her gung-ho, all-American cohort John Wayne (David James Elliott), he became a target, suspected of working with the Soviets simply for his political beliefs. Nevermind that Trumbo served America in WWII; Wayne, meanwhile, spent the war “stationed on a film set, wearing makeup.” Soon enough, Trumbo and others are asked to testify before HUAC in Washinton D.C. and admit they’re communists. As this was considered against the First Amendment, Trumbo and the Hollywood Ten refuse to answer such questions. They’re found in contempt of Congress and sentenced to jail time. When he gets out 11 months later, Trumbo determines to fight his enemies Hollywood the best way he knows how: write.

Wily and filled with determined contempt, Trumbo conceives a plan to write pictures for a D-movie producer (John Goodman, in Argo mode) under an anonymous pen name, eventually earning enough money to support his family (a wife played by Diane Lane, a daughter by Elle Fanning) with some major studio gigs under a series of pseudonyms. Though it takes a toll on his family life, in due course he wins two Oscars (for Roman Holiday and The Brave One) for his clandestinely applied skills. His clever manipulation of Hollywood turns his otherwise blacklisted talent—such as Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus and Otto Preminger’s Exodus—into a desired commodity, eventually eliminating the blacklist altogether.

Cranston’s bombastic, almost cartoonish performance lends the picture a quality of classic cinema, complete with exaggerated expressions and melodramatic dialogue (in the most enjoyable way possible). Much of the cast acts in this style, from Michael Stuhlbarg’s depiction of Edward G. Robinson to Dean O’Gorman’s version of Kirk Douglas. Fortunately, Roach does a splendid job of recreating scenes from these 1950s films; for example, O’Gorman is flawlessly injected into scenes of Spartacus. Movie buffs will appreciate the detail of these scenes; likewise, vintage-looking newsreel footage assembled by lenser Jim Denault and production designer Mark Ricker is a joy to watch from a level of pure craftsmanship. Overall, the film is a breezy and accessible testament to freedom of speech and belief, and there are countless modern-day parallels, from groups trying to suppress the right to gay marriage to other, less popular political stances held by those in power. Enduringly relatable, Trumbo is ultimately the story of an underdog besting a bully, and who doesn’t love stories like that?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review