Truly, Madly, Deeply

By Brian Eggert |

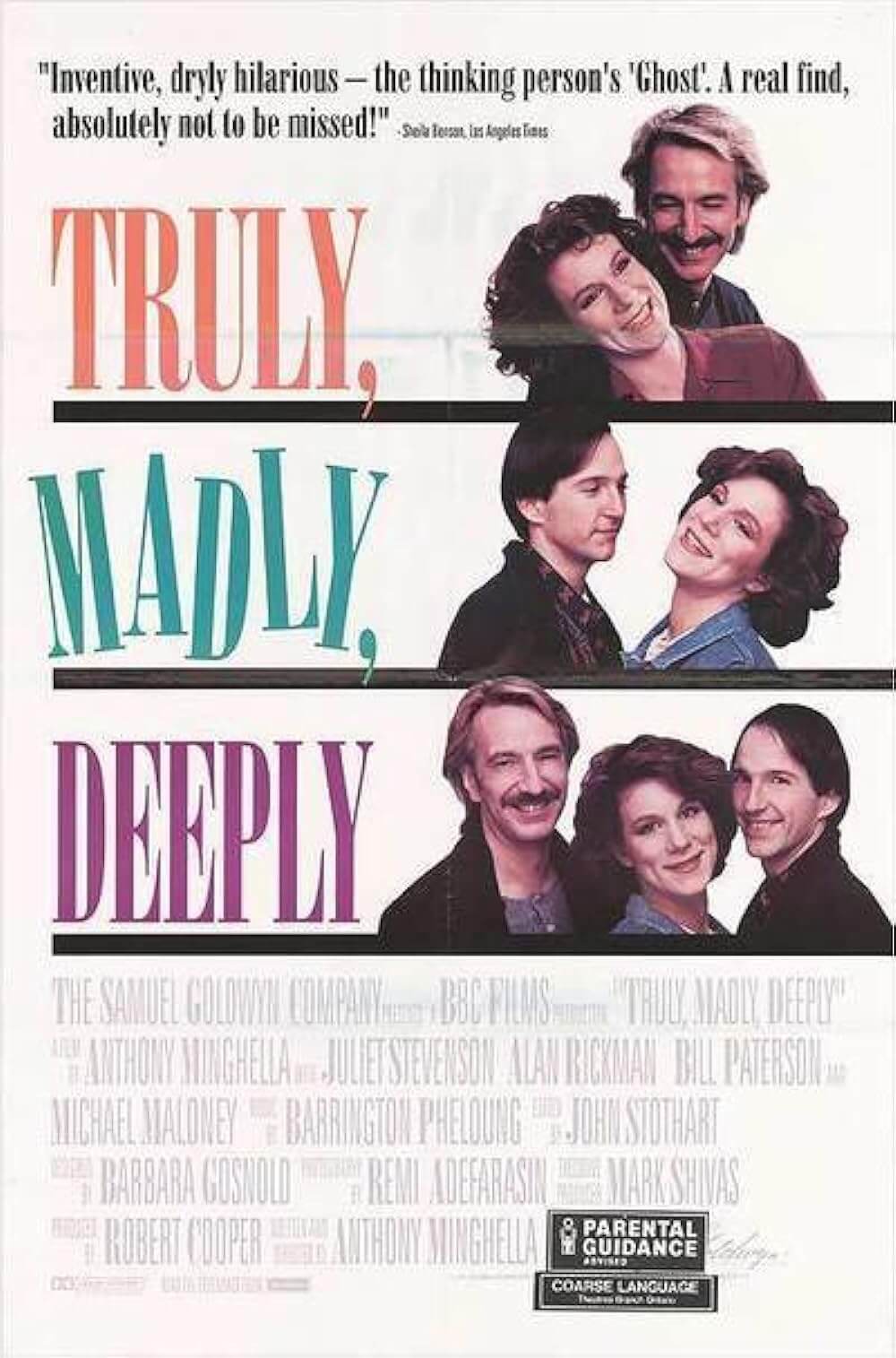

If you read a plot synopsis for Anthony Minghella’s Truly, Madly, Deeply, you might think the 1991 release was a cornball romance and dependent on a gimmick, resembling the previous year’s Ghost. Audiences swooned as Demi Moore grieved over the loss of her lover, while Patrick Swayze’s spirit, with the help of Whoopi Goldberg’s wacky medium, protected her from beyond the grave. But Minghella avoids relegating himself to the commercial treatment of a goofy concept and instills emotional substance into the material. Rather than a Hollywood yarn about romantic setups and supernatural thrills, the writer-director offers a thoughtful work about a woman so besieged by a sense of loss that her husband returns to ease her through the mourning process. But it’s possible to read the film another way, as though the ghostly aspects of Minghella’s story are imagined. After all, Truly, Madly, Deeply is more about letting go than an investigation into the afterlife or even a celebration of the loving relationship between the two main characters, one alive and the other dead. The presence of a ghost might take place entirely within the mind of the protagonist, although either way, real or imagined, Minghella’s dramatic symbolism leads to an exploration of profound loss—all with an intimacy that, next to the director’s later, sweeping epics like The English Patient (1997) or Cold Mountain (2003), feels warmly small in scale.

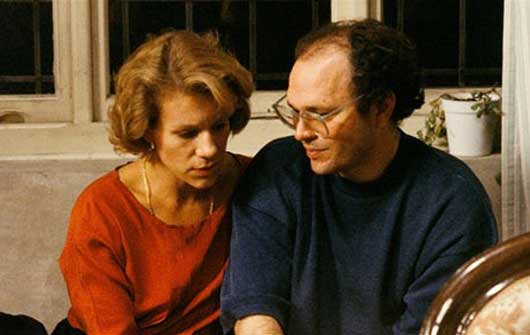

Before becoming a filmmaker, Minghella’s early career involved writing plays, directing stage adaptations for television, writing teleplays, and scripting for the BBC and Jim Henson’s shows The Storyteller and Living with Dinosaurs. In the late 1980s, he fielded offers to make either a film-length episode of Inspector Morse, a series based on the popular books by Colin Dexter, or write and direct his own, original work that would receive less attention. Minghella passed on the more prestigious offer and set out to write what would become Truly, Madly, Deeply. Minghella originally developed the film as a made-for-TV production for the BBC’s Screen Two series, which brought filmed plays to the small screen. He approached the work cautiously, with full awareness that, should he make a bad film, at least fewer viewers would see it. Similarly, he turned down a chance for a wider distribution deal by demanding that Juliet Stevenson, rather than an established and bankable screen star, appear in the lead role. A celebrated performer on the British stage, Stevenson was no marquee name, though she would go on to earn a BAFTA nomination for her performance in the film. The classically trained English actor Alan Rickman, however, was becoming more acknowledged all the time following his Hollywood roles in Die Hard (1988) and Quigley Down Under (1989), where he became typecast as the villain. Minghella used Rickman’s rarely tapped ability to play an everyman by casting him as the film’s ghost, a genial specter who grows increasingly chilly as the story progresses, and therefore appears, as all ghosts do in the film, in a black wool coat for warmth.

Perhaps because his idea was original and not an adaptation of a structurally complex novel, as he would adapt with Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) in later years, Minghella completed the script in four months, drawing from his established, naturalistic playwright style, as opposed to the more straightforward style he used in his television scripts. His stage style had an almost Mamet-esque rhythm of ellipses and pauses, which he used to convey the incoherence of natural communication. He observed that when speaking, people often stop and restart sentences, trying to convey their ideas by re-clarifying in the middle of a thought. He blended that naturalistic rhythm of dialogue with the fantasy genre, which was not known for such realistic modes, and explored the realm of ghosts in believable domestic scenes that still feel modern and organic.

Perhaps because his idea was original and not an adaptation of a structurally complex novel, as he would adapt with Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient and Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) in later years, Minghella completed the script in four months, drawing from his established, naturalistic playwright style, as opposed to the more straightforward style he used in his television scripts. His stage style had an almost Mamet-esque rhythm of ellipses and pauses, which he used to convey the incoherence of natural communication. He observed that when speaking, people often stop and restart sentences, trying to convey their ideas by re-clarifying in the middle of a thought. He blended that naturalistic rhythm of dialogue with the fantasy genre, which was not known for such realistic modes, and explored the realm of ghosts in believable domestic scenes that still feel modern and organic.

At the same time, Minghella’s dramatic structure relies on the rather poetic notion of the bond that occurs between two people when they play music together. Minghella had a close friend who died before the film’s release, and this friend held a weekly duet with another friend to play piano and clarinet. “I’ve never experienced the same kind of joy as when you are able to play music with other people,” remarked the director. “It’s such an intense, egalitarian and wonderful experience to sit down and make music with someone else.” With that experience in mind, and in part an homage to his friend’s lasting musical relationship, Minghella imagined what it might feel like to have that experience permanently robbed from them. This was the basis of Truly, Madly, Deeply, as his central couple, Nina and Jamie (Stevenson and Rickman), had played piano and cello respectively before Jamie’s death. Within such a relationship, even Jamie’s cello is a symbol of their bond after his death from a mysterious throat ailment. When Nina’s sister asks for the cello for her son, Nina, wounded, replies, “It’s like you’re asking for his body.”

The importance of ownership over objects, such as a cello, plays a considerable role in Nina and Jamie’s relationship, both before and after his death. When the film opens, Nina admits to her psychologist that she feels “looked after” by Jamie’s ghost, that his voice is constantly reminding her to lock the back door to the flat or brush her teeth before bed. The psychologist assures her this is a natural reaction among the bereaved. Later, we follow Nina home to a dingy, rat-infested, dilapidated flat, which she proudly maintains as her own since Jamie’s death. His sudden reappearance in her life as a spirit, while met with overwhelming joy and a welcomed reprieve from her sorrow, also reveals a subtle strain of animosity. Jamie’s nitpicks of Nina’s behavior, while fondly remembered quirks, soon become annoyances as he attempts to reorganize her flat to his liking. He moves chairs, hangs pictures, tosses out her favorite rug, and, given his ghostly coldness, demands a sweltering temperature inside. Before long, Jamie invites his ghost friends over to the flat to watch VHS tapes of old movies. They even take over Nina’s bedroom, which offers more space for the ghosts to spread out and debate what to watch next, Five Easy Pieces or Fitzcarraldo. Nina begins to realize the importance of rebuilding herself through the ownership of her own things and living space.

It’s around this time that Nina meets Mark (Michael Maloney), a kind if eccentric amateur magician to whom Nina shows some romantic interest. She soon agrees to a date with Mark, but a lingering fidelity to Jamie, with whom her complicated supernatural relationship is strained, prevents her from committing to the other man. Only when Jamie’s behavior in the flat reaches full annoyance, forcing Nina to want to leave, does she give Mark attention. The film’s dramatic structure shows us Nina’s heartbreak as a symbol of the relationship. But then, it shows us the relationship, such as it exists, between Nina and Jamie after he returns, so that we might better understand her grief. Within the rekindled romance, however, her grief subsides, and we come to understand that Nina’s extreme pain resulted from, perhaps, the suddenness of Jamie’s absence. Whereas Mark’s presence, along with the rising inconvenience of Jamie and his ghostly friends, draws that pain away from Jamie’s memory. Minghella’s apparitions, then, remain unconventional in his use of the afterlife as an allegory for grief.

It’s around this time that Nina meets Mark (Michael Maloney), a kind if eccentric amateur magician to whom Nina shows some romantic interest. She soon agrees to a date with Mark, but a lingering fidelity to Jamie, with whom her complicated supernatural relationship is strained, prevents her from committing to the other man. Only when Jamie’s behavior in the flat reaches full annoyance, forcing Nina to want to leave, does she give Mark attention. The film’s dramatic structure shows us Nina’s heartbreak as a symbol of the relationship. But then, it shows us the relationship, such as it exists, between Nina and Jamie after he returns, so that we might better understand her grief. Within the rekindled romance, however, her grief subsides, and we come to understand that Nina’s extreme pain resulted from, perhaps, the suddenness of Jamie’s absence. Whereas Mark’s presence, along with the rising inconvenience of Jamie and his ghostly friends, draws that pain away from Jamie’s memory. Minghella’s apparitions, then, remain unconventional in his use of the afterlife as an allegory for grief.

Minghella is concerned most with his characters’ internal lives. He validates their human complexity, a characteristic that is true of every one of his seven feature-length films. On the periphery of his central narrative, he included details that reflected his humanism and empathy by simply treating marginalized figures with respect. No character in a Minghella film was ever one-dimensional. Titus (Christopher Rozycki), a Polish immigrant and Nina’s super, has a tender subplot about his unrequited love for his tenant, but he’s never reduced to a comic device. Or take Nina’s job as an interpreter, where we meet Maura (Stella Maris), a Spanish woman who’s learning English. Maura and her doctor friend experience linguistic discrimination from an intolerant restaurant owner in one sequence, only to be defended by both Mark and Nina. Elsewhere, Mark’s occupation as a caretaker of persons with intellectual disabilities shows the group without prejudice and a derisive eye. Whereas so many films refuse to give agency to such marginalized characters, Minghella offers positive representations and adds a thoughtful, human texture to his film.

Unlike Ghost, Minghella offers no confirmation of the spirit world; no one else sees Jamie (or his spectral compadres), nor does the spiritual world overlap with reality in a tangible way, outside of Nina’s mind. It’s entirely possible to read Truly, Madly, Deeply as a film about the power of grief. The first scene establishes doubt when Nina speaks to her psychologist about her sense that Jamie is watching her from beyond the grave, reminding her to lock her doors at night and, oddly enough, speaking Spanish, something Jamie could not do in life. Maybe Nina’s own work with Maura has planted an unconscious seed of learning the Spanish language. Whatever the reason he speaks in another language to her at times, Jamie’s presence in her mind serves as a mechanism created by her psyche to protect itself from a complete breakdown. Only when she meets Mark does her extreme grief subside, allowing her to remember how she and Jamie often bickered about their shared living space or, besides music, didn’t have as much in common as she remembered. The chief counterpoint to this argument, though, is Jamie’s final appearance in the window, which Nina does not see, where Jamie shows a sense of pride as he watches Nina and Mark together, as though he has successfully helped his lover move on—presumably his goal all along.

As Truly, Madly, Deeply was planned for television initially, the film was shot with a boxy 4:3 aspect ratio, adhering to the popular square shape in an age before widescreen televisions. The production’s cinematographer, BBC craftsman Remi Adefarasin, imparted his skill onto the new director, but Minghella remained a novice in visual terms. “If they’d have given me $100 million to make Truly, Madly, Deeply it probably would have looked exactly the same because I didn’t know what else to do,” he remarked. Despite his inexperience, Minghella makes good use of cramped spaces and few locations. He was given artistic freedom, and his cut was unquestioned by distributors, a phenomenon that would not always be the case in the future. The film was first distributed into theaters in England and the United States, where it was well received. For his work, Minghella won a BAFTA for Best Original Screenplay. In the U.S., the film was distributed by The Samuel Goldwyn Company, which made a deal with Minghella to direct his next film, Mr. Wonderful (1993). Even though Samuel Goldwyn had a business model dependent on small budgets, small returns, and small risk, Mr. Wonderful bombed. Nevertheless, Minghella found that Truly, Madly, Deeply had many admirers; among them were Sydney Pollack and Saul Zaentz, who would produce the director’s remaining films.

As Truly, Madly, Deeply was planned for television initially, the film was shot with a boxy 4:3 aspect ratio, adhering to the popular square shape in an age before widescreen televisions. The production’s cinematographer, BBC craftsman Remi Adefarasin, imparted his skill onto the new director, but Minghella remained a novice in visual terms. “If they’d have given me $100 million to make Truly, Madly, Deeply it probably would have looked exactly the same because I didn’t know what else to do,” he remarked. Despite his inexperience, Minghella makes good use of cramped spaces and few locations. He was given artistic freedom, and his cut was unquestioned by distributors, a phenomenon that would not always be the case in the future. The film was first distributed into theaters in England and the United States, where it was well received. For his work, Minghella won a BAFTA for Best Original Screenplay. In the U.S., the film was distributed by The Samuel Goldwyn Company, which made a deal with Minghella to direct his next film, Mr. Wonderful (1993). Even though Samuel Goldwyn had a business model dependent on small budgets, small returns, and small risk, Mr. Wonderful bombed. Nevertheless, Minghella found that Truly, Madly, Deeply had many admirers; among them were Sydney Pollack and Saul Zaentz, who would produce the director’s remaining films.

A formative marker in Minghella’s transition from television to a resounding, if too-short career in film, Truly, Madly, Deeply is an often funny but mostly touching film of rich characterizations. Although it’s not akin to the sumptuous visual epics to which he was later associated, it bears the same thoughtfulness of his final theatrically released work, Breaking and Entering (2009). His literate treatment contains moments where Nina and Jamie reminisce about their favorite love poem from Pablo Neruda, they perform a duet of Bach, or they compete in a series of affectionate adverbs in a love scene that inspired the title. Somewhat difficult to see in the U.S., the film remains underseen outside of England, where it maintains the status of an essential romantic comedy. Of course, Minghella elevates his film into more than just a rom-com, more than another version of the surprisingly common situational comedy involving a romance between a member of the living and a ghost—from The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) to Just Like Heaven (2005). Truly, Madly, Deeply exists, like its characters, outside of easily describable conventions, and like a complex friend or lover that takes time and consideration to know, so too does this film.

Sources:

Bricknell, Timothy (edited by). Minghella on Minghella. London: Faber & Faber, 2005.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review