Reader's Choice

True Lies

By Brian Eggert |

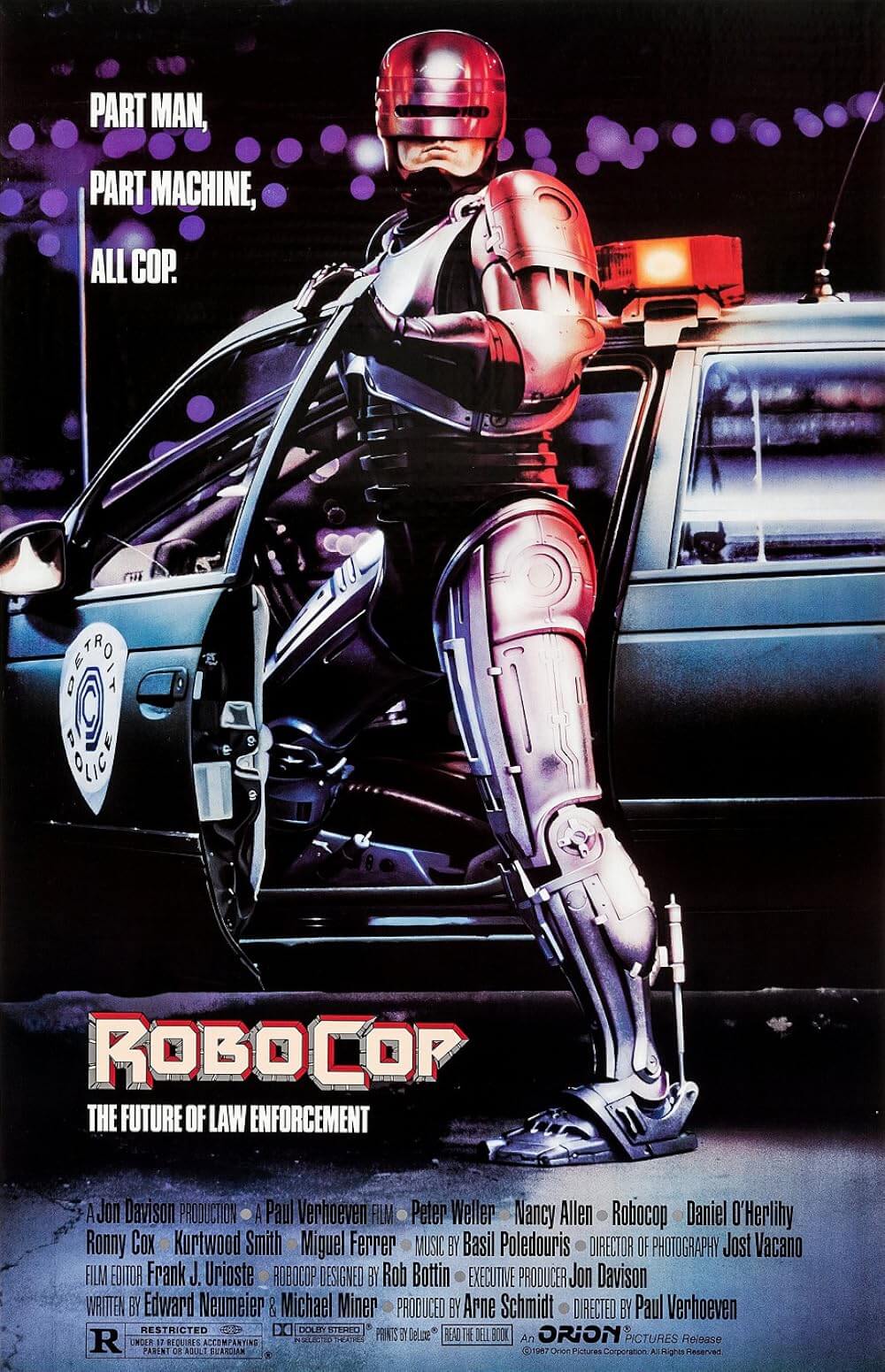

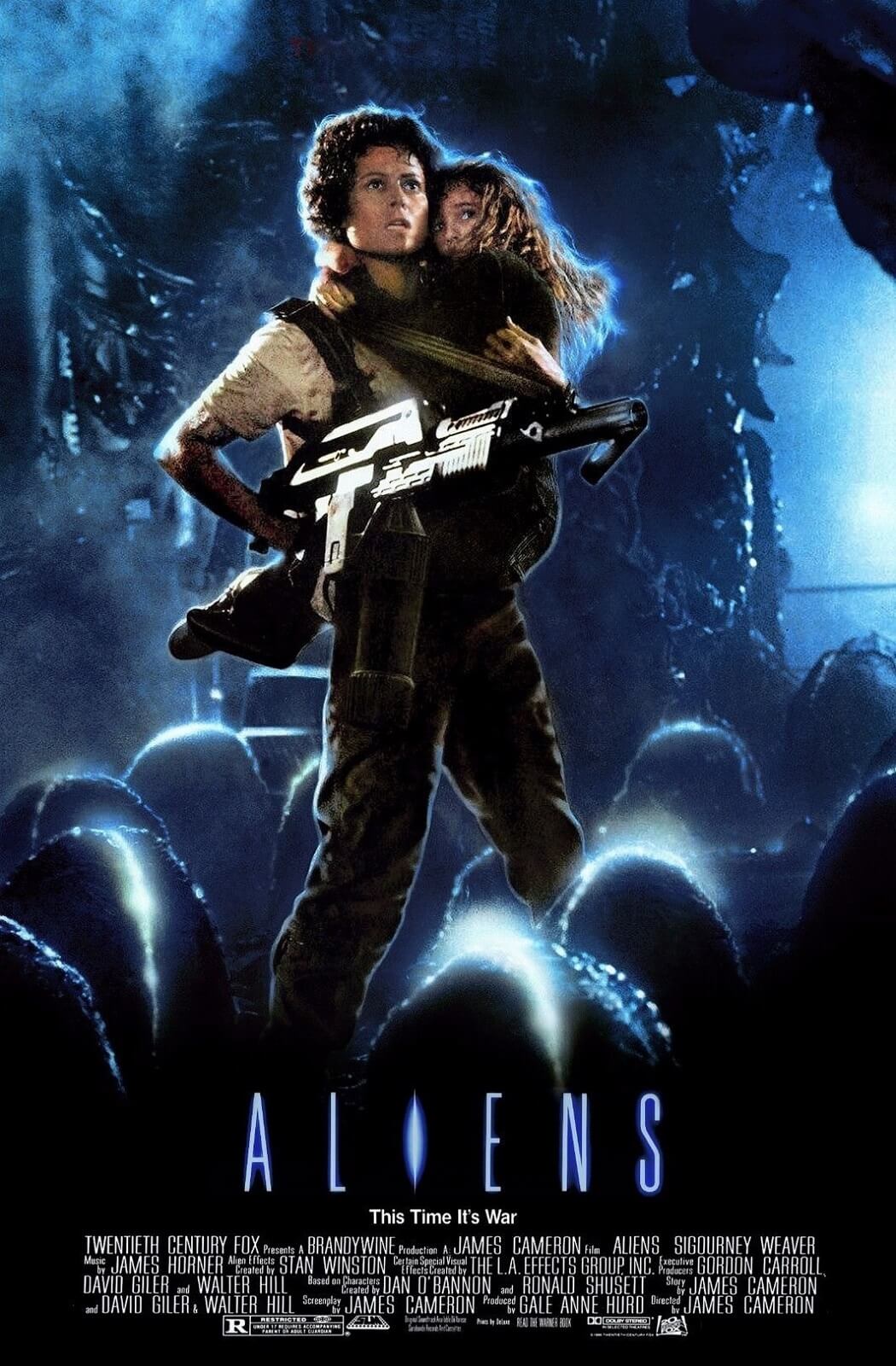

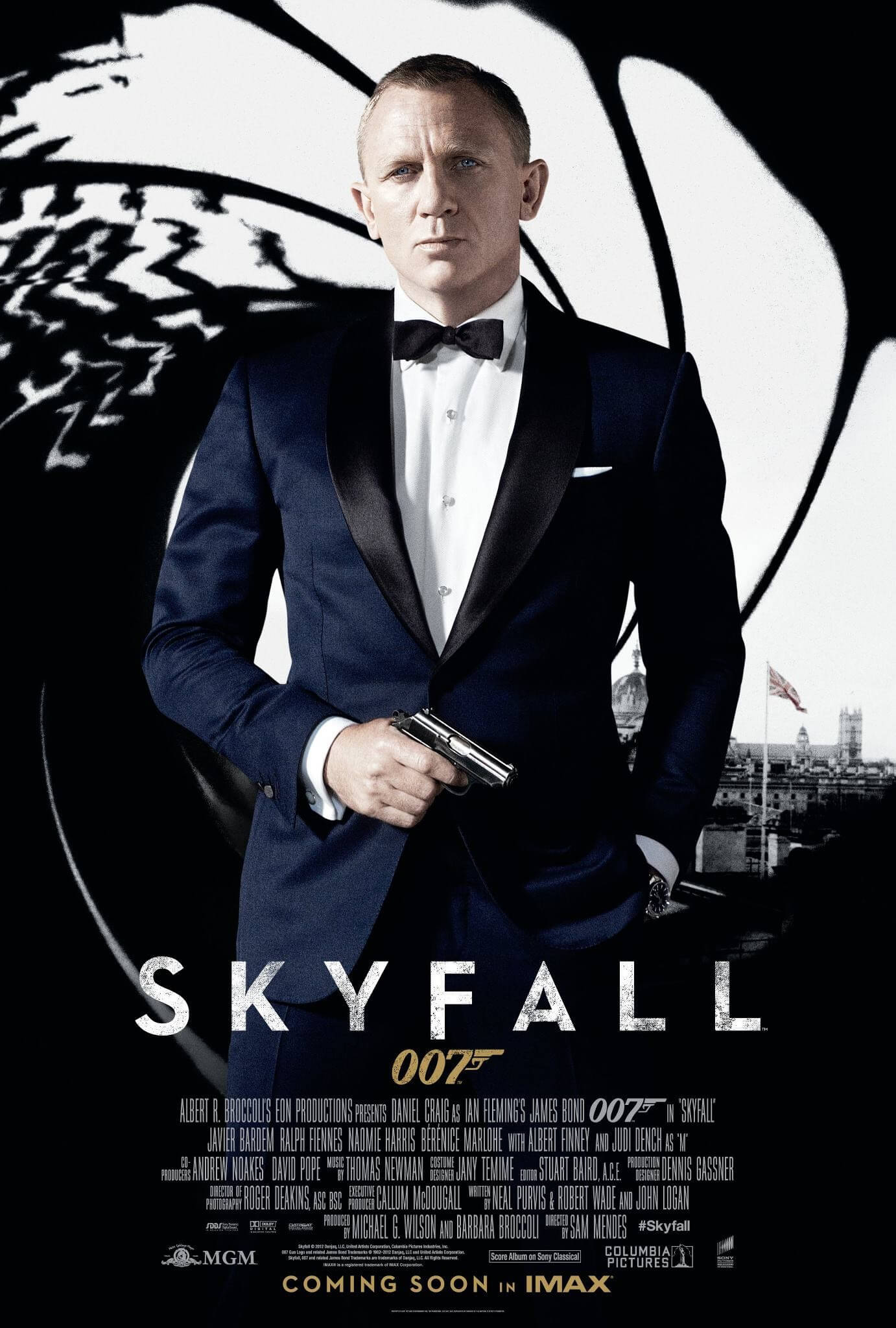

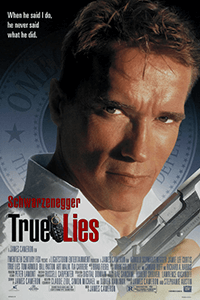

James Cameron made True Lies after three prolonged, arduous, back-to-back productions on Aliens (1986), The Abyss (1989), and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991). He wanted to make something light and breezy, so he set out to fashion a crowd-pleaser with Arnold Schwarzenegger, adopting a popular mode of action extravaganza with hints of James Bond and domestic comedy. It ended up being another of his famously long and expensive productions. But where usually the ends justify the price tag and effort, True Lies, while fun and boasting a few memorable sequences, doesn’t amount to much. It feels like a throwaway effort from a filmmaker who often weaves heavy sci-fi themes into groundbreaking cinema and who establishes new standards for spectacle. Rewatching True Lies for the first time in over 20 years, I found myself thinking the material was, perhaps, beneath Cameron. While a well-executed shoot-em-up, armed with a bevy of uneven jokes and several wowing set pieces, there’s not much more to the experience than some diverting fun. Perhaps it’s a testament to Cameron’s talent and accomplished filmography elsewhere that the 1994 feature, an action movie that might feel like a superior work for, say, Renny Harlin or other action directors from this era, plays like a minor effort from him.

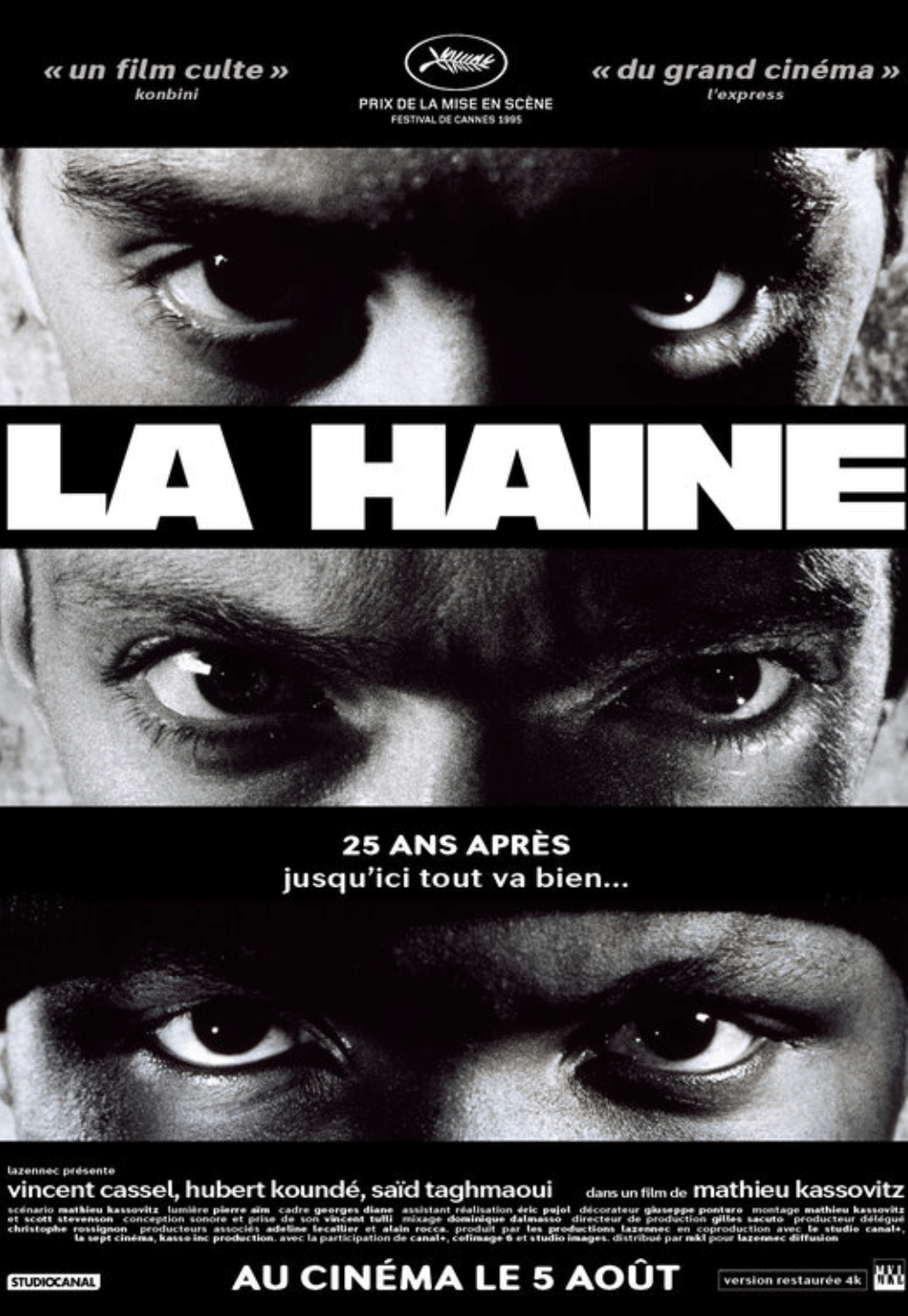

Cameron based the scenario on a French movie by filmmaker Claude Zidi called La Totale! (1991), recommended to him by Schwarzenegger. The director loved what he saw: “An anti-James Bond, a reality check on the uber-male fantasy” that acknowledged “as a man you still had to answer to a woman when you came home.” From this, one might be tempted to read into Cameron’s view of marriage at this time, not to mention his understanding of gender roles and relationships between men and women. Cameron was thrice divorced by the early 1990s and now expecting his first child, with Linda Hamilton, whom he would marry and divorce later in the decade. His film portrays a marriage that suggests a free-spirited husband who sees his nagging wife as an almost parental figure. Questions arise: Is that how Cameron saw his relationships, thus leading to his divorces? Why should someone have to “answer to” their partner and face punitive consequences? The appeal to Cameron is a character who can maneuver any espionage situation with finesse, yet he cannot manage his home life and almost loses his family. The result might be a critique of this worldview, with Cameron underlining that marriages thrive on honesty, except the main characters don’t learn much about improving their marriage along the way.

Cameron had managed to portray killer cyborgs, xenomorphs, and underwater NTIs, but his new project would require him to try something new: comedy. Although rooted in science fiction to this point, he had coupled those interests with plenty of action. The director could handle the technical stuff—the guns and the explosions. But could he handle quips, gags, and physical humor? Cameron tapped his friend Randall Frakes to help complete the script, uncredited, along with a bevy of comedy writers to punch up the material with humor. While they helped him with the humor, Cameron selected a villain that reflected current political anxieties. Instead of the Soviet threats that purveyed so much action cinema of the previous decade, Cameron settled on a Middle Eastern threat. He even became anxious during his research, learning how easy it would be for religious fanatics to smuggle weapons into the country. So as not to give anyone ideas, Cameron avoided realism and went with an intentionally outlandish set of circumstances. Even so, the monologue recorded on a camcorder by Salim Abu Aziz (Art Malik), the head terrorist, plays with unsettling prescience in retrospect. Delivered eight years before the 2001 attacks on 9/11, the ultimatum given by Aziz to the US now registers like many such videos by similar groups since.

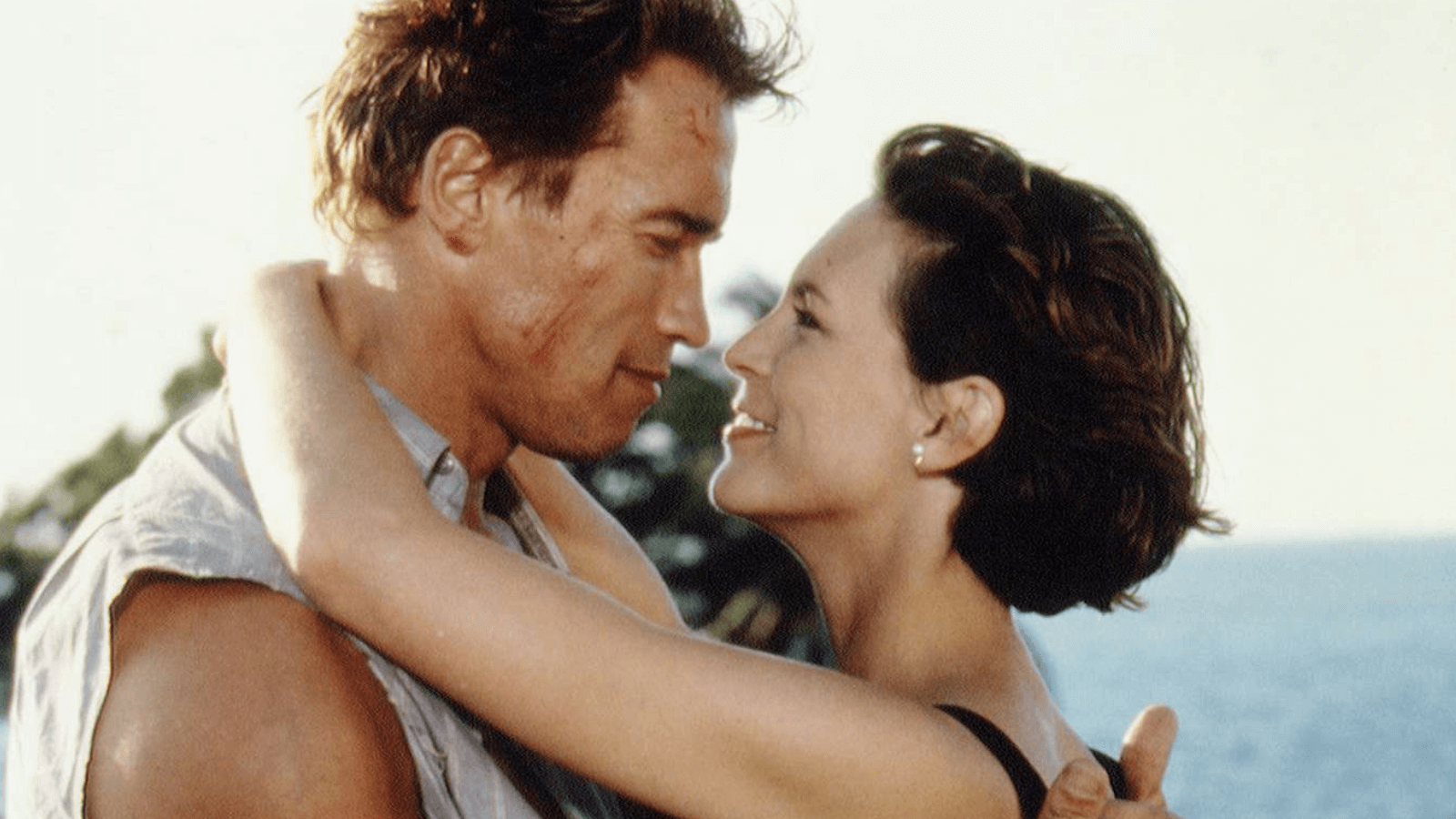

The setup follows Harry Tasker (Schwarzenegger), a superspy who leads a double life. Harry maintains a cover as a family man and computer salesman. He’s husband to Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis) and father to rebellious teen Dana (Eliza Dushku). The family isn’t a plant; it’s genuine, but they’re unaware of his real job: an agent in a US counterterrorism unit. Harry’s eye-patch-wearing boss (Charlton Heston, a nod to Nick Fury by Cameron, a Marvel Comics fan) runs the top-secret Omega Sector (another nod, this one to Heston’s 1971 hit, The Omega Man). While Harry tries to track down members of a group called the Crimson Jihad in Switzerland, his absence at home causes a rift. Of her unreliable husband, who constantly breaks his promises, Helen has resigned herself to saying, “You know Harry.” When he learns that Helen may be having a secret rendezvous with another man, Harry uses his intelligence resources to spy on her. Inevitably, the two sides of Harry’s life come crashing together, putting his family at risk from the Crimson Jihad. Aziz discovers Harry’s identity and kidnaps the couple, along with their daughter, prompting Harry to reveal his secret life, rescue his family, and stop the bad guys.

The setup follows Harry Tasker (Schwarzenegger), a superspy who leads a double life. Harry maintains a cover as a family man and computer salesman. He’s husband to Helen (Jamie Lee Curtis) and father to rebellious teen Dana (Eliza Dushku). The family isn’t a plant; it’s genuine, but they’re unaware of his real job: an agent in a US counterterrorism unit. Harry’s eye-patch-wearing boss (Charlton Heston, a nod to Nick Fury by Cameron, a Marvel Comics fan) runs the top-secret Omega Sector (another nod, this one to Heston’s 1971 hit, The Omega Man). While Harry tries to track down members of a group called the Crimson Jihad in Switzerland, his absence at home causes a rift. Of her unreliable husband, who constantly breaks his promises, Helen has resigned herself to saying, “You know Harry.” When he learns that Helen may be having a secret rendezvous with another man, Harry uses his intelligence resources to spy on her. Inevitably, the two sides of Harry’s life come crashing together, putting his family at risk from the Crimson Jihad. Aziz discovers Harry’s identity and kidnaps the couple, along with their daughter, prompting Harry to reveal his secret life, rescue his family, and stop the bad guys.

For his cast, Cameron wanted Jamie Lee Curtis as Helen. They met when she was filming Blue Steel (1990) under the direction of Kathryn Bigelow (Cameron’s wife at the time), and he had Curtis in mind when writing Helen Tasker. However, Schwarzenegger wasn’t convinced Curtis could play the role. After months of screen-testing other actresses, and possibly landing on Jodie Foster, they hadn’t found a suitable alternative. Then Cameron caught up with A Fish Called Wanda (1988) and was reminded how Curtis was more than her scream queen persona from Halloween (1978) or comic presence in Trading Places (1983); she could also be charming, funny, and sexy. Cameron returned to Schwarzenegger and asked the star to trust him: Curtis could pull off Helen. To Schwarzenegger’s credit, he trusted his director and never again expressed doubt about his costar. Similarly, Cameron auditioned Tom Arnold for Harry’s agency sidekick, Gib, and loved him for the part. Everyone around the production questioned Arnold, an obscure goof labeled an opportunist for his marriage to Roseanne Barr and his contributions to her popular ABC sitcom. Oblivious to Arnold’s reputation, Cameron liked his “manic” quality and cast him to bring a more chaotic tone to the scenes with the comparatively rigid Schwarzenegger.

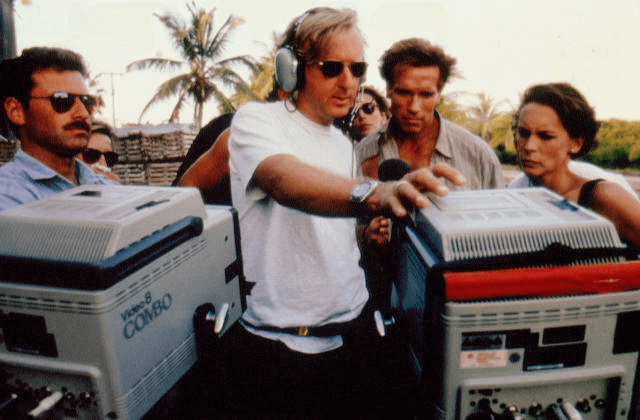

True Lies became the first project to materialize from a five-year deal made in 1992 between Cameron and 20th Century Fox, which agreed to back the director’s production company, Lightstorm Entertainment. In the deal, Cameron had creative control to greenlight any project with a budget of less than $70 million, and Fox would distribute domestically. Among the films to come out of the deal were Strange Days (1995), directed by his ex-wife Kathryn Bigelow and co-scripted by Cameron, and the remake Solaris (2002) directed by Steven Soderbergh. However, the deal with Fox had a wrinkle that required Cameron to provide a detailed budget in advance of securing a completion bond, a required contract that ensures a film will be completed on schedule and budget. This meant Cameron had to convince Fox to pay for any overages on the initial $60 million budget, which, of course, he would need. In typical Cameron fashion, the budget continued to balloon throughout the course of the six-month shoot, which started in the sweltering Miami heat of August 1993 and continued in Los Angeles after the Northridge earthquake that registered 6.7 on the Richter Scale. Delays due to Cameron’s perfectionism and on-set improvisations doubled the budget to a reported $120 million, then one of the most expensive films ever made.

Consider the sequence of Harry’s shootout in a Washington D.C. mall restroom, which was supposed to be completed in one day of filming but instead took five. One of the film’s best set pieces—rivaled by a similar bathroom brawl in Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)—the shootout became increasingly elaborate under Cameron’s direction. He added ever more bombastic details while filming, such as Aziz shooting out the stall doors, only to have Harry leap for his gun by sliding in water from broken pipes and toilets (yuck). Cameron’s insistence on the toughest but also the most authentic way to accomplish visuals meant further challenges. When a scene called for Harry to fly a Harrier jump jet on which Dana is perched, Cameron used some digital effects. But he also built a full-size fiberglass model three hundred feet above Miami for a convincing and dangerous stunt. Other setups, such as when Harry chases Aziz onto a hotel rooftop, and the bad guy races his motorcycle through a glass barrier and flies across to a rooftop pool on an adjacent building, haven’t aged well in visual terms. Then again, they never looked that good.

Consider the sequence of Harry’s shootout in a Washington D.C. mall restroom, which was supposed to be completed in one day of filming but instead took five. One of the film’s best set pieces—rivaled by a similar bathroom brawl in Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018)—the shootout became increasingly elaborate under Cameron’s direction. He added ever more bombastic details while filming, such as Aziz shooting out the stall doors, only to have Harry leap for his gun by sliding in water from broken pipes and toilets (yuck). Cameron’s insistence on the toughest but also the most authentic way to accomplish visuals meant further challenges. When a scene called for Harry to fly a Harrier jump jet on which Dana is perched, Cameron used some digital effects. But he also built a full-size fiberglass model three hundred feet above Miami for a convincing and dangerous stunt. Other setups, such as when Harry chases Aziz onto a hotel rooftop, and the bad guy races his motorcycle through a glass barrier and flies across to a rooftop pool on an adjacent building, haven’t aged well in visual terms. Then again, they never looked that good.

Unlike his previous two features, the last few decades have not been kind to several moments in True Lies, which, due to their clunky execution, take the viewer out of the story today. Note how many contemporary action movie stars—Tom Cruise, Keanu Reeves, Charlize Theron, etc.—perform many of their own stunts, or alternatively, the production uses CGI to create a digital mask to hide the stunt worker’s face. The latter technology was available in 1994 and had been used the previous year on Jurassic Park. However, throughout True Lies, scene after scene features Schwarzenegger’s stunt doubles for mid-to-wide shots, yet the stuntman’s non-Arnie face is unmistakable and remains incongruent. Compare that to the incredible helicopter and car chase shot on the Seven Mile Bridge to the Florida Keys, where Curtis insisted on authenticity. She wanted to be rigged to the helicopter for her close-up, where Schwarzenegger holds onto her arm as she dangles outside, hooked up to a thin safety wire. The sequence rivals similar hanging-from-a-helicopter scenes in Sam Raimi’s Darkman (1990) and Stanley Tong’s Supercop (1993). It’s also the most convincing and awe-inspiring stunt in Cameron’s film, complete with a limo crashing beneath Curtis and her writhing in the air. But it’s all set to one of Brad Fiedel’s most generic-sounding scores.

At the time, True Lies was considered a top-notch production, with effects realized by Cameron’s newly founded company, Digital Domain, featuring key members of Industrial Light & Magic, the effects house that had accomplished the breakthrough CGI on The Abyss and T2. The eventual release, bowing in the summer of 1994, earned $379 million worldwide, making it the year’s third highest-grossing film after The Lion King and Forrest Gump. Mild controversy followed, with protests from Islamic and Muslim groups about Cameron’s simplistic depiction of Middle Eastern characters, and indeed, the movie often resorts to gross stereotypes. Malik’s role, in particular, becomes cartoonish in the climactic jet sequence, with crotch hits and wide-eyed reaction shots that make the material play like a Looney Tunes cartoon. More troublesome is the general air of misogyny conveyed by Arnold’s character, whose use of the term “bitch” for every woman onscreen becomes grating. Amid the mostly positive reactions from critics, some complained that the movie’s misogynistic overtones tainted their enjoyment, citing the scene where Helen must strip for a clandestine Harry, whom she believes is a French spy.

The second act contains the best parts of True Lies, with Harry suspecting that Helen is involved with Simon, a “mystery man” who turns out to be a greasy used car salesman (Bill Paxton) acting the part of an international spy to get her into bed. Behind his ishy mustache and greasy hair, Paxton is a perfect sleaze who can’t help but brag about his deception and sexual conquests. But his eventual breakdown when confronted by Harry and other actual spies (“I’m nothing! I’m navel lint!”) remains a movie highpoint, even if Cameron dully returns to the peed-his-pants joke unnecessarily in the final scene. However, the subplot also leads to the only affecting scenes in the movie, when Harry and Gib interrogate Helen from behind a two-way mirror. When she explains why she pursued Simon—“I needed to feel alive. And it felt good to be needed,” she says—it’s the movie’s sole note of tenderness. Curtis is also excellent here, playing the only dimensional character in the movie. Afterward, Harry comes up with a solution to Helen’s domestic boredom: he intends to create a spy fantasy for her, requiring her to play the role of a sexworker and dress like a dancer in a Robert Palmer music video.

The second act contains the best parts of True Lies, with Harry suspecting that Helen is involved with Simon, a “mystery man” who turns out to be a greasy used car salesman (Bill Paxton) acting the part of an international spy to get her into bed. Behind his ishy mustache and greasy hair, Paxton is a perfect sleaze who can’t help but brag about his deception and sexual conquests. But his eventual breakdown when confronted by Harry and other actual spies (“I’m nothing! I’m navel lint!”) remains a movie highpoint, even if Cameron dully returns to the peed-his-pants joke unnecessarily in the final scene. However, the subplot also leads to the only affecting scenes in the movie, when Harry and Gib interrogate Helen from behind a two-way mirror. When she explains why she pursued Simon—“I needed to feel alive. And it felt good to be needed,” she says—it’s the movie’s sole note of tenderness. Curtis is also excellent here, playing the only dimensional character in the movie. Afterward, Harry comes up with a solution to Helen’s domestic boredom: he intends to create a spy fantasy for her, requiring her to play the role of a sexworker and dress like a dancer in a Robert Palmer music video.

The reactions to this scene were a point of contention. Roger Ebert called Harry’s scheme “cruel and not funny.” But Caryn James, writing in the New York Times, argued that the scene showed Helen’s humanity and defied the stereotype of a stuffy wife, calling it “liberating.” Anne Thompson argued in Entertainment Weekly that the scene lacked an exploitative quality, noting that it was “not at all icky for me.” Certainly, the sequence aligns with the era’s third-wave feminist notion of empowering oneself by embracing and having control of their sexuality, selfhood, and desire, making Helen’s realization that she can be sexy a vital facet of her identity. After all, it’s not about Harry playing a joke on his wife (well, maybe a little); it’s about a husband helping his wife live out her fantasy—to be caught up in a sexy spy scenario. Cameron originally intended to shoot the scene in silhouette, with Curtis nude and seen only in shadow. However, Curtis pitched having Helen visible in her underwear and adding a note of humor when she falls while straddling a bedpost. Cameron and Curtis planned the scene without Schwarzenegger’s knowledge, and when she fell on the first attempt, the actor’s genuinely shocked reaction appears in the movie.

Unfortunately, Cameron never confronts any of these marriage or sexual dynamics convincingly or meaningfully. While Curtis is up for anything, Schwarzenegger never quite pulls off the hunky leading man role, demonstrating little romantic chemistry with his (or any) costar. Watching Schwarzenegger navigate a romantic relationship is not part of what makes him appealing as an actor, so his presence feels misplaced here. Ultimately, Cameron’s signature brand of relentless action remains escapist fun. But it’s an empty experience that takes for granted how Harry and Helen resolve their issues—not through words, such as when a truth serum influences him, but when Harry rescues Helen, and he becomes her fantasy hero. Their problems are solved with a kiss while an atomic explosion detonates in the distance. While a single scene of actual marital discourse may have justified the happy ending, as is, True Lies is a diverting 141-minute yarn that gets so swept up in the spy action that it forgets to adequately address the personal conflicts it creates. It remains Cameron’s most unsatisfying effort in terms of narrative and formal execution, yet it feels far superior to many of its action movie contemporaries from the 1990s.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on March 14, 2024.)

Bibliography:

Keegan, Rebecca. The Futurist: The Life and Films of James Cameron. Three Rivers Press, 2009.

Nathan, Ian. James Cameron: A Retrospective. Palazzo Editions, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review