True Grit

By Brian Eggert |

Having mastered the revisionist Western with No Country for Old Men, Joel and Ethan Coen return to the genre for a more classical Western tale with True Grit, an adaptation closer to Charles Portis’ source novel than the 1969 film version starring John Wayne. The Coens’ version earns its title with dark humor and grim violence in a more mainstream format than the filmmakers are accustomed to. Their film doesn’t attempt to deconstruct or make commentary on the genre as so many Westerns do these days; rather, they simply tell a good story, which is brave in a way. Their approach might even be called old-fashioned for the straightforwardness of its storytelling. Except, the ever-dynamic Coens infuse their proclivity for ironic, straight-faced wit into the dialogue, much of it straight from the novel, adding a layer of unexpected stylization that serves as their signature.

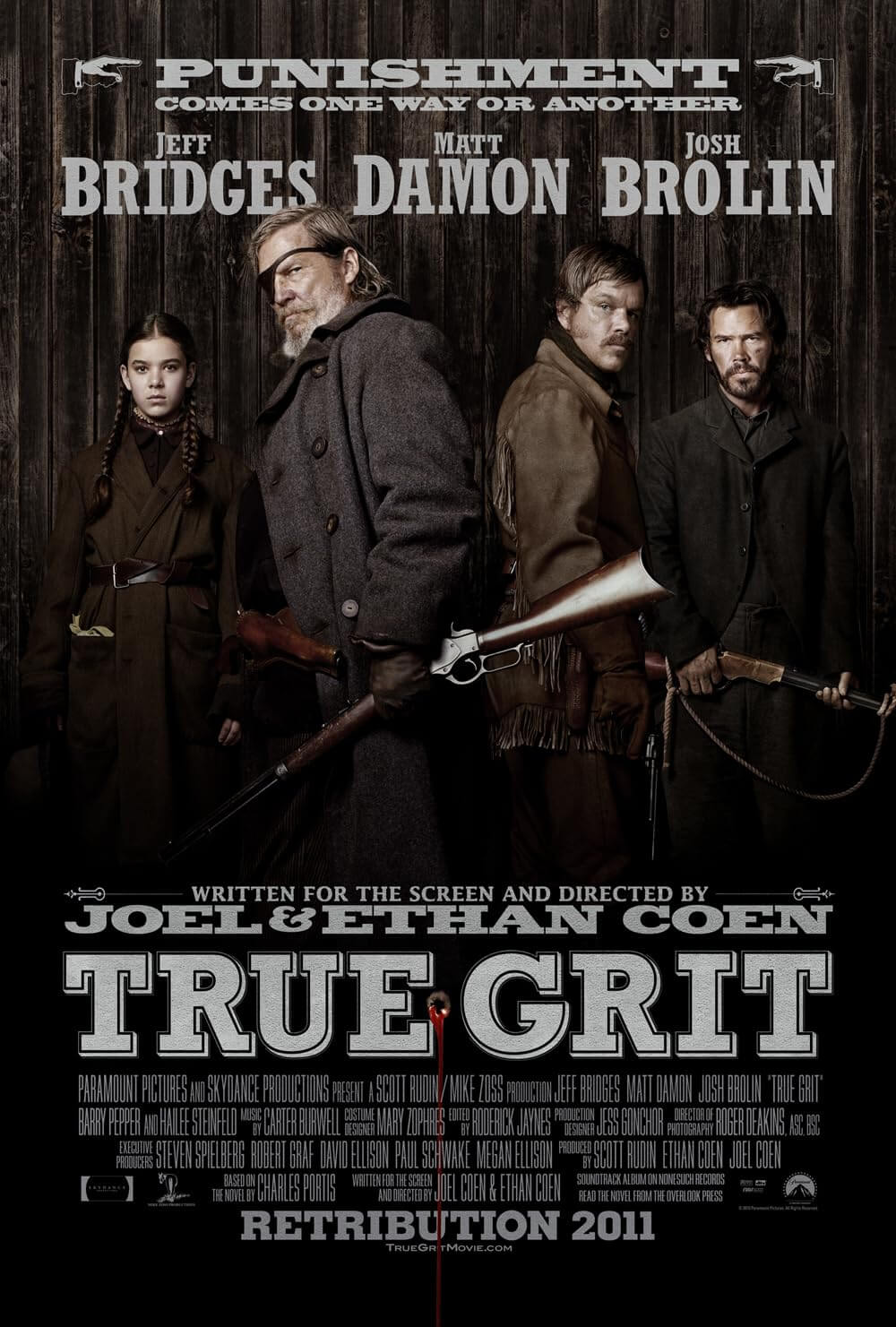

In remaking a beloved John Wayne film, one containing a performance that earned Wayne an Oscar, the Coens expose themselves to potential dismissal from The Duke’s devotees. Despite having legendary shoes to fill, they’ve reteamed with their star from The Big Lebowski, Jeff Bridges, fresh off his own Oscar win. Bridges’ performance as Rooster Cogburn, the craggily, boozehound gunslinger with an eyepatch, not only stands on its own but completely reinvents the role in ways that, frankly, Wayne could never have accomplished. Supporting Bridges are Matt Damon, Josh Brolin, and Barry Pepper, each giving depth to their roles that otherwise felt so one-dimensional in the original. What’s more, the central role of retribution-hungry 14-year-old Mattie Ross, as performed by Hailee Steinfeld in her first screen appearance, is given enough spirit to contend with even Bridges’ colorful portrayal.

But more than any single actor, the Coens have bettered the rather dry direction of the original’s Henry Hathaway, whose tired approach left the material dated by a 1960s stain, leaving it perfect material for a remake. Aspects of the original True Grit that feel awkward today are polished in the Coens’ script, which makes full use of Portis’ authentic 1880s colloquialisms, including the complete lack of contractions in much of the dialogue. When Cogburn looks upon a corpse and utters, “I do not know this man,” there’s a matter-of-factness to the delivery that the words underscore. The Coens stress such proper language of the period, adhering to Portis’ novel and filling their exchanges with archaic turns of phrase for moments of pitch-perfect humor, such as when Mattie minces words while bargaining with a stubborn horse trader.

Much about the 1969 film and this one are similar in terms of plot, aside from the Coens’ embrace of the book’s grittier epilogue. The events of the story, now familiar to Wayne enthusiasts, are almost identical. The young Mattie Ross hires the notorious U.S. Marshall Rooster Cogburn to hunt down her father’s murderer (Brolin). They’re joined by a Texas Ranger named La Beouf (Damon), whose deficiency as a tracker is exceeded by his bravery and honor. The La Beouf role has the greatest expansion, and Damon makes a bland character from the original (played by Glen Campbell) into a loveable one here. All the stops and major events in the story are the same, including the climactic shootout. But each is imbued with the Coens’ focused narrative economy and singular tone, tightening the story to make the most of each encounter on the trail. As always, the Coens have refined their film with both craft and artistry.

Take the over-sentimentalized scene from the original where Wayne’s Cogburn pours his heart out to Mattie one night, recounting his tragic past with a hardened yet vulnerable exterior, and thus explaining away why Cogburn later feels a connection to the girl. That barefaced scene never occurs in the Coens’ version; Bridges’ Cogburn prattles on about his past to Mattie over several scenes, his recollections offering few answers to this complex character. Cogburn and Mattie’s relationship, which grows as Cogburn comes to respect her as an equal, develops through the plot and how Mattie handles herself. It becomes apparent that the title, in fact, refers to Mattie, and perhaps not Cogburn here, whereas the same cannot be said for Hathaway’s version. Steinfeld conveys her character’s strength of resolve by standing proudly among the cast of great actors. Yet, she also demonstrates Mattie’s vulnerability as a teenage girl in this era, a crucial element lacking in Kim Darby’s original portrayal.

Moreover, Wayne brought perhaps too much dignity to his role as a “one-eyed fat man,” but the Coens introduce Bridges’ Cogburn quite differently. When searching for her avenger, Mattie meets Cogburn, unflatteringly, through an outhouse door. Before he’s even on screen, the Coens demystify a character whose legend is known through the land, rendering him human. Just as the Coens have made a career of telling stories about deeply flawed characters, Bridges has always excelled at portraying them (it’s what earned him that Oscar for Crazy Heart). He captures the skilled gunslinger’s highs and wobbly drunkard lows with uncommon humanity. Yet, the performance boasts larger-than-life heroism that allows Bridges to display his character’s flaws and lawman skill as the scene demands.

Living up to the title, the film pushes its PG-13 rating to the limit, displaying Wild West violence in all its unromanticized detail. In an effort to make a crowd-pleasing John Wayne Western, Hathaway’s version earned itself an undemanding G-rating, which hardly feels challenging enough given the themes. Where possible, the Coens keep to Portis’ novel and include just as much sharp humor as they do ugly truths about the West. All of this gets across in Coens’ particular tone, which distances itself from the earlier adaptation and compliments the source material. Gone are the original’s lengthy picturesque vistas, where all at once the film stops to regard the gorgeous backdrop just because it’s gorgeous. Cinematographer Roger Deakins, a regular on the Coens’ films, employs stunning camerawork but never pulls away from the characters or the story. Likewise, the original’s grating epic Western score by Elmer Bernstein seemed written for another film entirely. Here, Carter Burwell embraces music more fitting to the period, including the closing song “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” which those familiar with The Night of the Hunter will remember as a hopeful song performed under wounded conditions.

True Grit belongs on a shortlist of remakes—including John Carpenter’s The Thing, David Cronenberg’s The Fly, John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, and Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear and The Departed—that have outdone their originals. All the original flaws, including John Wayne’s usual strut, come crashing down compared to the Coens’ precision storytelling and Bridge’s layered performance. This may be the most crowd-pleasing film of the Coens’ career, but it’s made with all the trademark artistry, surreal tone, and humor that has become expected from their work. With just the right amount of archetypes and innovation, the Coen Brothers have made a Western that aligns with the classicism of John Ford and the edge of Anthony Mann, and it deserves a place among the best modern entries in the genre.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review